In common with so many other aspects of our lives, fifties children had no say in what they wore. For much of the year, our parents seemed to prefer us layered like the prize in a game of pass the parcel. Sleeves down to the wrist, necklines up to the chin, and long socks which met the hems of skirts or shorts.

I can only assume that the practice of making children ‘grow into’ their clothes was somehow perceived as character building. In my experience, the moment a garment started to fit, it was handed down to a younger sibling or cousin, to grow into in their turn.

Retro fashion may be ‘in’, but the quantity of unlovely underwear regarded as essential would horrify today’s children.

Back then, leaving the house without a vest was considered tantamount to a death sentence.

For children, vests were sleeveless cotton in summer and itchy wool in winter.

I imagine the loose fitting underpants boys wore were considerably more comfortable than girls’ drawers with that circulation-stopping elastic in the leg.

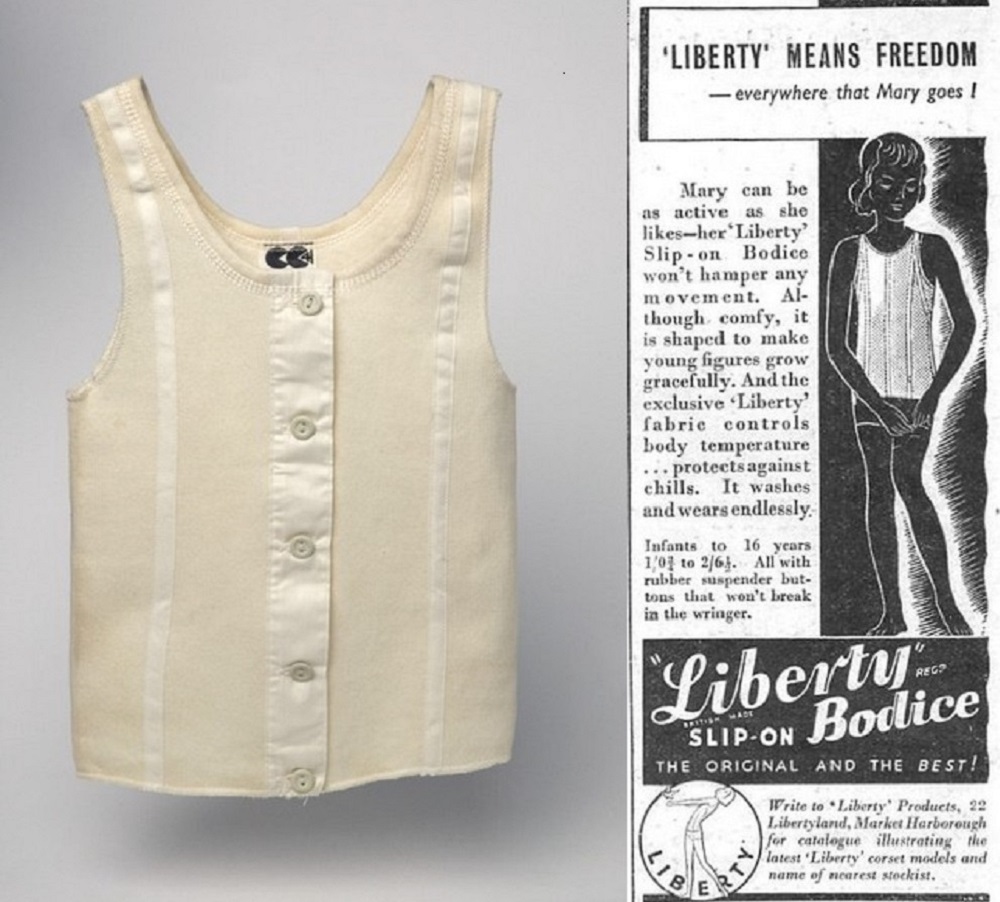

Liberty bodices kept youngsters of both sexes warm throughout the fifties. The garment was first introduced by the 19th century ‘Rational Clothing Movement’ as an alternative to boned stays (corsets). The innovation had the added benefit of liberating girls from the combinations my grandmother was forced to wear. The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory).

The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory).

In the interests of equality, the layer represented by a girl’s full length winceyette underskirt, was matched by the sleeveless pullover boys wore on top of a shirt.

Both sexes wore knee length woollen winter stockings which required garters to keep them up. In summer it was ankle socks (white for girls) worn with crepe sole, T-bar sandals or pumps (known locally as gollies).

As a shy child, the anonymity of a compulsory uniform suited me. From the age of seven I went to school in a navy serge, box pleated gym slip and white cotton blouse. Ties, girdles and stripes at the hem of navy cardigans, varied in colour according to which ‘house’ we belonged to. Our hats were threepenny bit shaped and, like the non-compulsory blazer, were purple. For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts.

For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts.

The garment most universally hated by all kids was the full length gabardine mac. It didn’t keep us dry, and certainly wasn’t warm enough in winter.

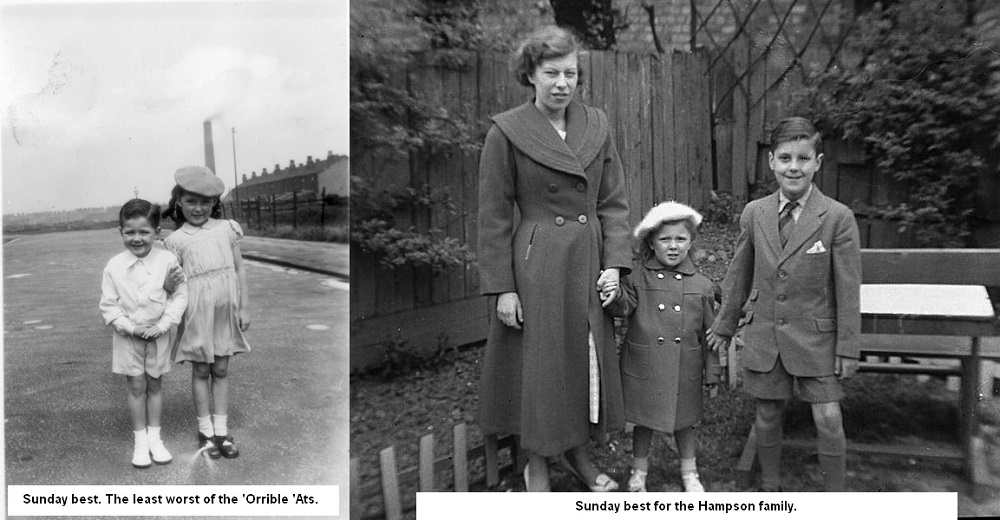

It’s possible the working classes were introduced to the idea of ‘best’ clothes by the custom of Whit walks. Mine were bought at C & A’s January sales, but it would have been regarded as sacrilegious to put them on before Whit Sunday.

With the exception of woollen bonnets or balaclava helmets, children’s headwear was singularly useless for keeping hair dry or ears warm. It must therefore be assumed that hats were strictly for show, or in my case for ridicule.

‘Where did you get that ‘at’, would have been an appropriate signature tune for me. I can still recall the torture of going to Sunday school in a cherry red monstrosity shaped like a dustbin lid, Or even worse, the pink one resembling an inverted po. Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent.

Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent.

My sister started school in 1957, and her age group were about the first to benefit from the relaxation of the rigid rules about how children should be dressed. She escaped the torment of ‘orrible ‘ats. Sadly it was too late for me, and I bear the mental scars to this day.

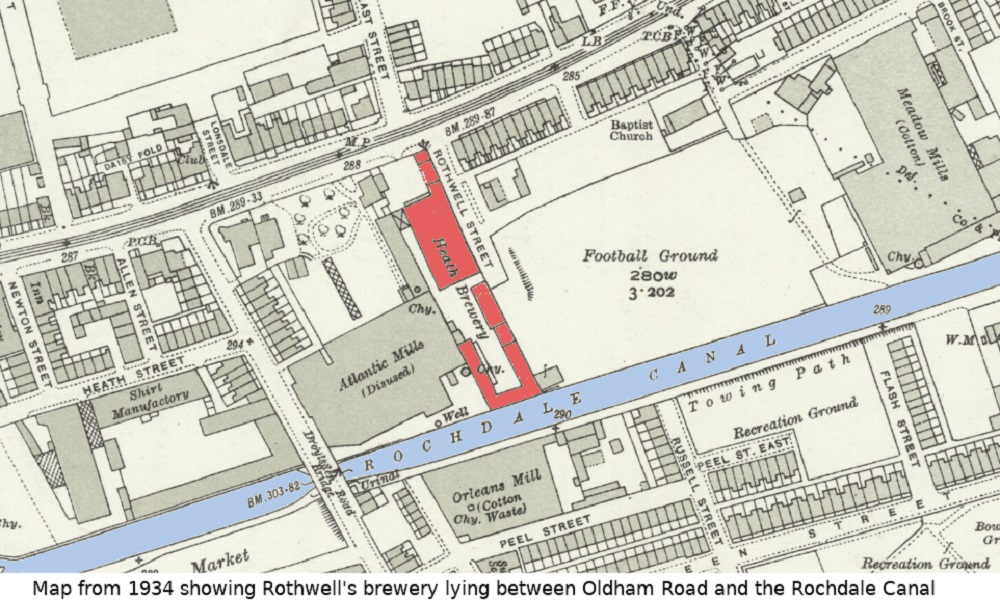

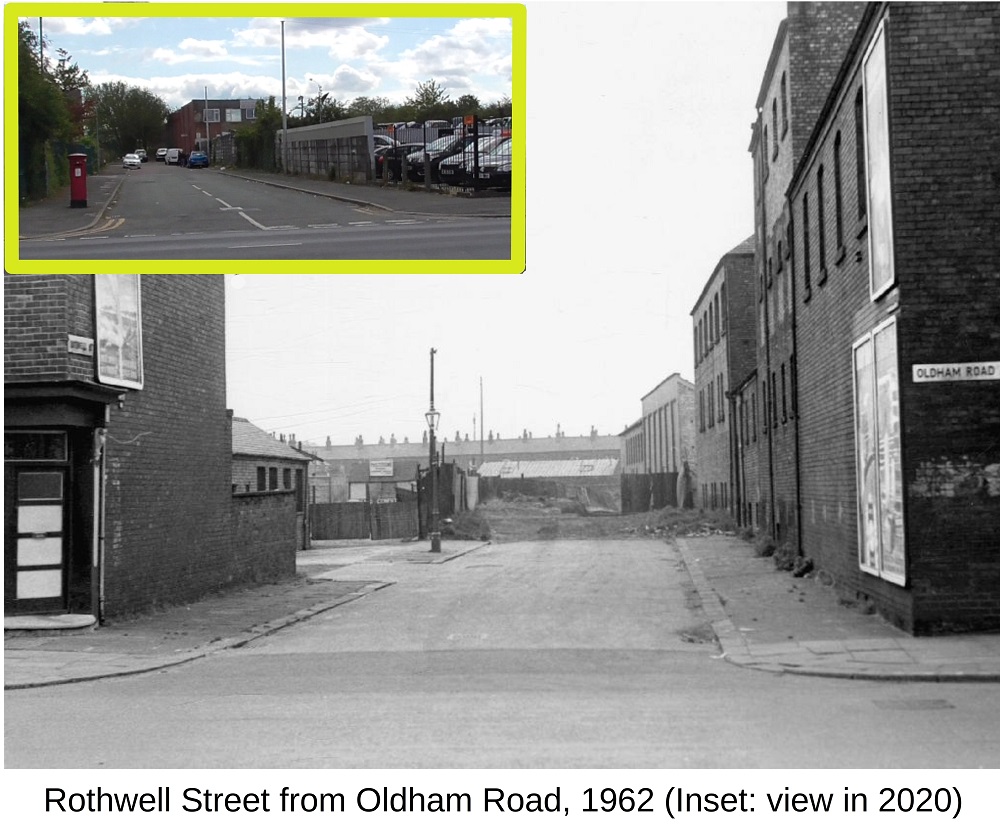

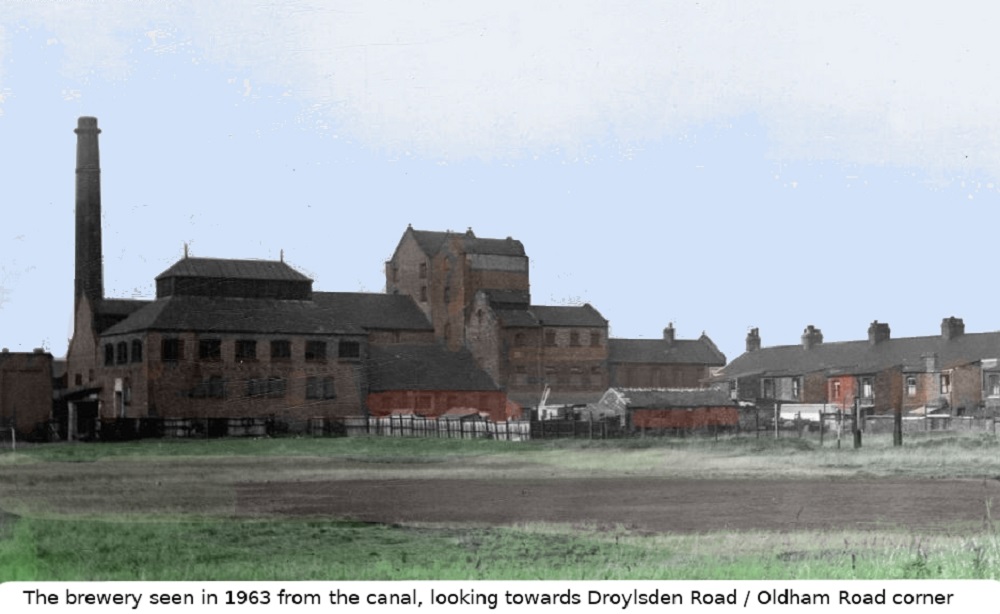

William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery.

William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery. William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33.

William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33. Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such.

Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such. Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth).

Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth). The Black Horse in 2009

The Black Horse in 2009