Our school yards were far from being the playing fields of Eton, but they were the place we developed non-academic skills that have lasted a lifetime.

For instance, by manipulating an intricately folded piece of paper, and offering you a selection of options, I could tell your fortune. And although I learned the skill nearly 70 years ago, I can still make a Christmas cracker out of a hankie.

Up to age seven, we were ‘mixed infants’, and playtime activities tended to be choreographed by adults. Ring games like ‘farmer’s in his den’, ‘poor Mary sat a weeping’ and ‘in and out the woods and bluebells’ were the sort of gentle games they favoured. A good tug-of-war at the end of ‘London Bridge is falling down’ was the best you could hope for.

Left to our own devices, juniors often played games that were reserved especially for the school yard. Two I recall were ‘The big ship sails through the Alley, Alley O, and ‘the whip’.

The latter was sometimes banned because of its lethal consequences, the least of which was a bitten tongue or bloody nose. To play, a line of kids linked arms and the leader ran pell mell, twisting and turning. Praying to stay on their feet, the tail-end Charlies covered twice the distance of the front runners at warp speed, flailing about like rag dolls.

For girls, an activity lacking a chant was the equivalent of dancing without music. Clapping games like ‘my mother said, I never should, play with the gypsies in the wood’ and, ‘each peach, pear plum’ were popular.

At playtime, there would be several long ropes, each with girls either skipping or waiting their turn to skip, all chanting rhymes that seemed to have been universally known. One of these was ‘Nebuchadnezzar the king of the Jews, bought his wife a pair of shoes’, etc. The most popular had actions or cues for the next skipper to enter the rope. ‘I was in the kitchen, doing a bit of stitching, in came a bogey man and pushed – me – out’ (exit first skipper) is an example.

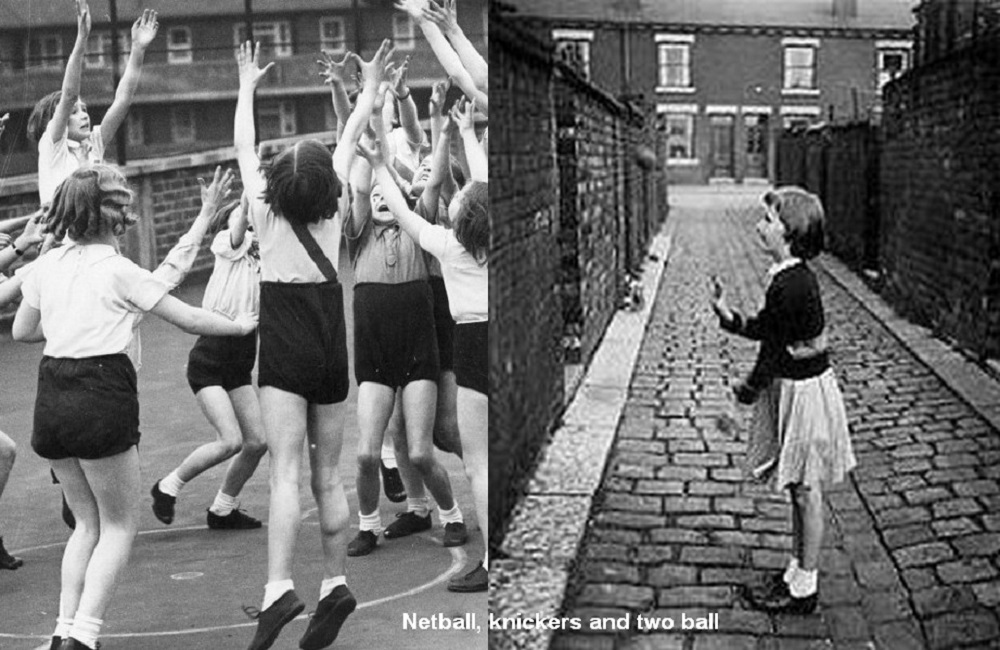

At playtime, you might see a girl standing with arms outstretched reserving a ‘two ball’ wall until friends arrived. The attractive looking sponge balls from the newsagents had a sloppy bounce compared to tennis or hollow rubber ones. But as long as they bounced, a good two baller could cope successfully with the most ill matched specimens.

According to which of the extensive repertoire of rhymes we chanted, actions included passing one of the balls around your back, under the knee, or tossing it up vertically while keeping the other in play.

Dipping was employed for deciding things like who would be ‘piggy in the middle’, or ‘first ends’ at skipping. Possibly the best known was ‘Dip, dip, dip, my blue ship’, but ‘eany, meany, miney, mo’ was also common.

With no school field, our games lessons took place in the yard. But unlike one school in Ancoats, ours was at least on ground level. George Leigh Street was one of several city centre schools to have a ‘sky’ playground on the roof.

In the juniors, games equipment seems to have consisted of little more than bean bags and wooden hoops. Some activities demanded jumping between hoops laid on the ground, but otherwise we used them for skipping races. Before the hula hoop craze came along, nobody had the imagination to twirl it around their middle.

We played netball, because the harder balls used in rounders were more likely to break a window or end up in the traffic on Kenyon Lane. Stripped down to blouse and navy knickers, the older girls first had to erect the portable netball posts. Teams were chosen, and different coloured woven bands distinguished one from another.

At my first school, the sexes were separated by a high wall which resulted in gender specific games. To judge by boys’ street games, that wall hid much rushing round the yard with outstretched arms being Spitfire pilots, or thigh slapping as cowboys, not to mention British Bulldog.

At nine, I moved to a ‘mixed’ school where ‘kiss chase’ was played. I modestly stayed loyal to games like skipping or two balls (for a while at least).