For centuries, fairs were welcomed as a break from the drudgery and monotony of everyday life. In the fifties, touring fairs were pretty small scale. Road locomotives were still being used to shift heavy equipment as well as providing electricity for lights and that unique fairground sound.

A whisper that the Showman’s wagons had been spotted would send a ripple of anticipation running through any district.

By hook or by crook, every kid was determined to visit the fair. To raise money, some ran errands and others cajoled adults into parting with bottles which had a few coppers back when returned to the shop.

Back then, waste ground, parks or playing fields were where fairs set up. In Moston, one of the regular fair sites was some land on Lily Lane, which I think belonged to the brick works. It was near my school and I recall some of the small hand-operated roundabouts opening in the afternoon. I presume they made a few bob from the mothers of young children being collected from school.

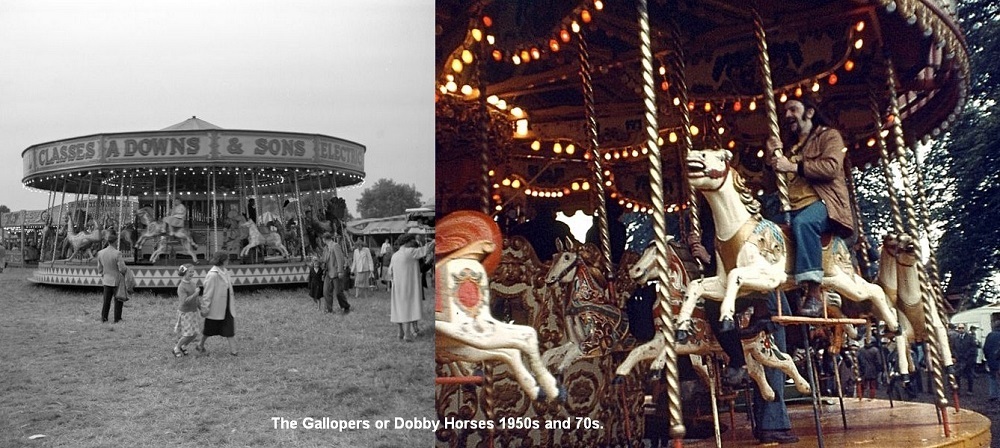

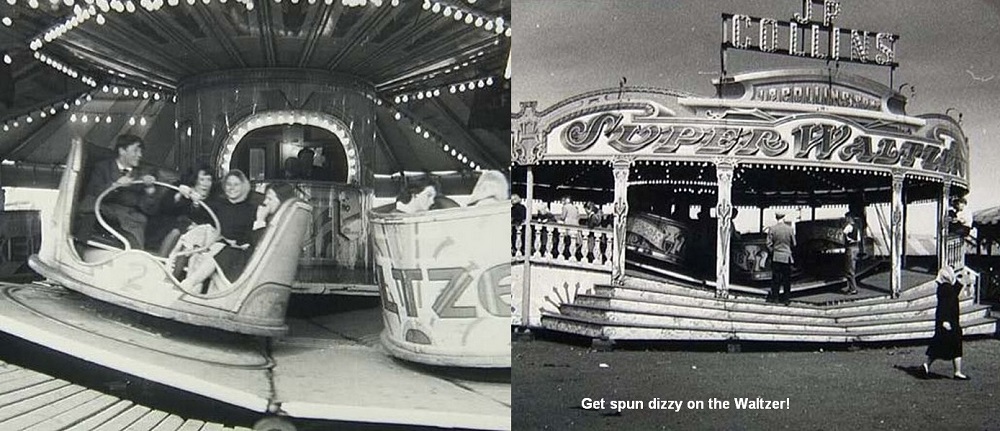

The biggest of the evening rides were the waltzer and the dodgems. One year I seem to recall a (relatively) Big Wheel. I was (and still am) afraid of heights, so that one wasn’t for me. My favourite was the ride introduced in 1891 which was originally called the ‘English gallopers’.

In the 1920s, a BBC advisory committee on the standardisation of English suggested the name ‘gyratory circus’ for what is commonly called a roundabout. I’m certain it would have taken more than the BBC to persuade my grandad to adopt that mouthful for what he called ‘dobbiwakes’. And thanks to him, the ‘gallopers’ are still known as ‘dobby horses’ in our family.

Half of most fairgrounds were given over to booths and stalls offering prizes. Dads and older lads gravitated towards the ones where they could demonstrate their prowess with darts thrown at playing cards, rifle shooting or chucking miniature mopheads at a pile of tin cans.

Coconut shies were popular with everyone, but the target nuts appeared to be cemented in place. As the prize was generally an ancient, dried-out coconut, those long odds against winning were sometimes a blessing.

We kids preferred games of pure chance such as roll the penny, hoop-la or getting a ping pong ball to drop into the narrow neck of a round fish bowl.

The dolls offered as prizes seemed to be peculiar to fairgrounds. For years I longed for a bride doll. When my dad unexpectedly turned my dream into reality, I changed my mind and opted for one dressed in maroon crinoline and bonnet. To this day, I can’t explain my contrariness.

Before decimalisation made them redundant, most of the country’s copper coins must have passed through the innards of a fairground slot machine numerous times. Those old machines acted like a magnet for our precious spending money, and all we got was a few seconds watching a little silver ball whizzing around before it vanished again.

New Moston was a little unusual in having a golf course side by side with a railway line and an abandoned coal pit. The golf club held an annual open day which included a small fair with swing boats, chairaplanes and roundabouts, plus a variety of booths eager to part us from our money.

Some of the more novel stalls were run by the club members themselves. One I recall was a row of enamel buckets lying on their sides with the rims propped up at a slight angle. Standing a considerable distance away, you threw one of your three golf balls at the buckets. The idea was to make it stay inside without bouncing straight out again. I think the prize was sweets, which I could have bought at the corner shop for the threepenny bit I risked for the 3 goes with the golf balls.

Our back windows overlooked Nuthurst Park. The fair came every year, and watching it being set up was an entertainment in itself. Sadly, once the activity ceased, daylight made the silent rides and booths appear disappointingly tawdry.

But when darkness fell, the scene was completely transformed. Somehow, a circle of coloured light bulbs and the insistent throbbing of that unique music, managed to create the illusion that the best place in the world to be was amongst that milling crowd.