In the 30 years after Moston’s incorporation into Manchester, education and culture gradually became more accessible to ordinary people, a new transit system was introduced, and a global pandemic arrived.

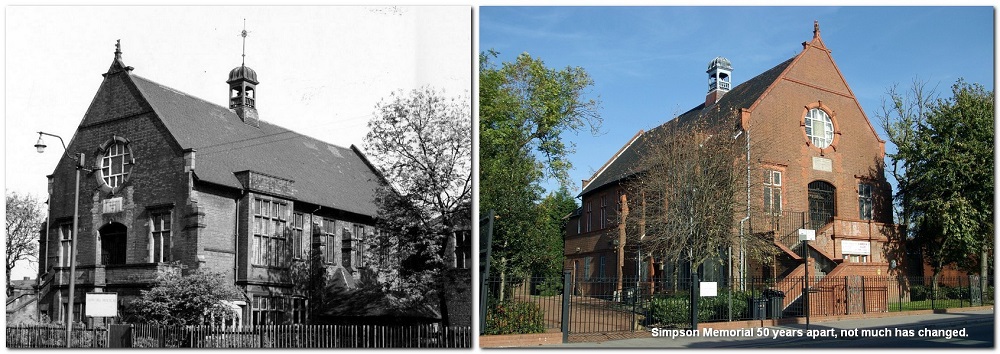

Named for William Simpson, a silk manufacturer, the Simpson Memorial was a truly local affair. The building was designed by architect Joseph Gibbons Sankey, son of the match manufacturer (of The Lane – Part 1). Opened in 1888, ‘the Simpson’ was initially staffed by volunteers, only becoming part of Manchester’s library service ten years later.

Access to the grounds and library was free to Moston residents, but non-residents had to pay 1 shilling (5p) per year. As well as university extension lectures, there were classes in subjects as diverse as Art and Pitman’s Shorthand. Amateur operatic, drama and horticultural societies were based there, as were camera, bowling and tennis clubs.

In 1899, the foundation stone of Moston Lane School was laid. It was to be the 32nd Manchester Board school, and had places for 1,230 pupils.

On weekdays, the hall of St. George’s Presbyterian Church, Moston Lane, accommodated pupils from a private school. Despite its small size, the standard of education at the grandly named Belmont High school, enabled some girls to win scholarships for Harpurhey High School.

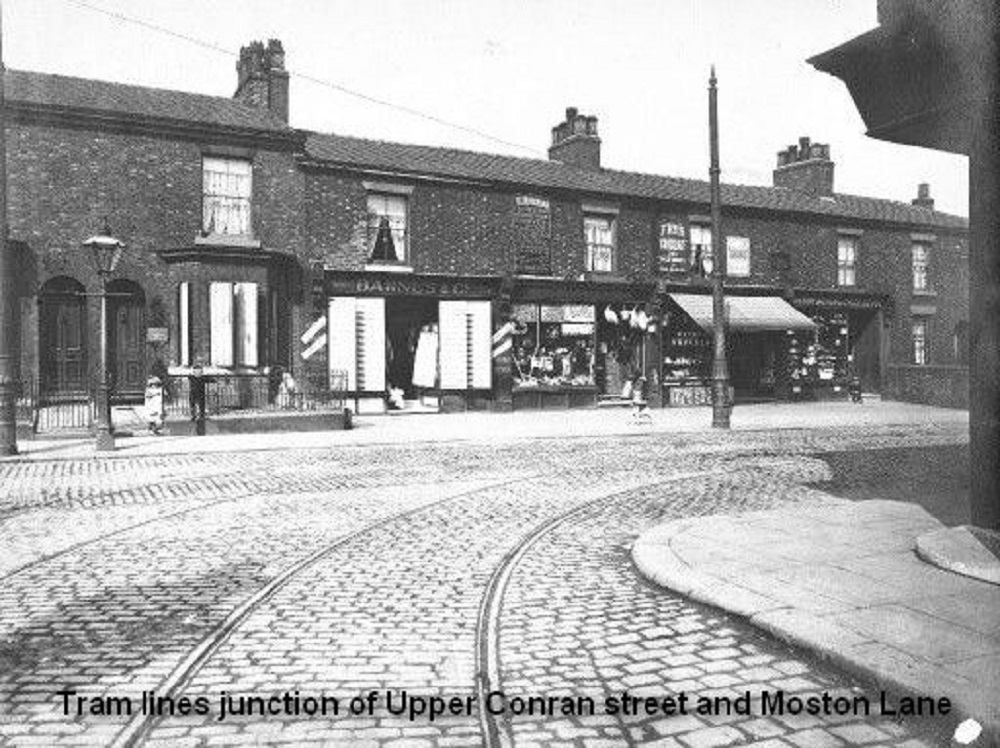

Land to build the Queen’s Park Tram Depot was purchased in 1900. By June 1901, the electric trams were in service. In 1915, trams became the most used form of city transit, and women were taken on to replace the men away fighting at the front

During the post war pandemic, James Niven, Medical Officer of Health, suspended tram services to help prevent the spread of the deadly Spanish Flu.

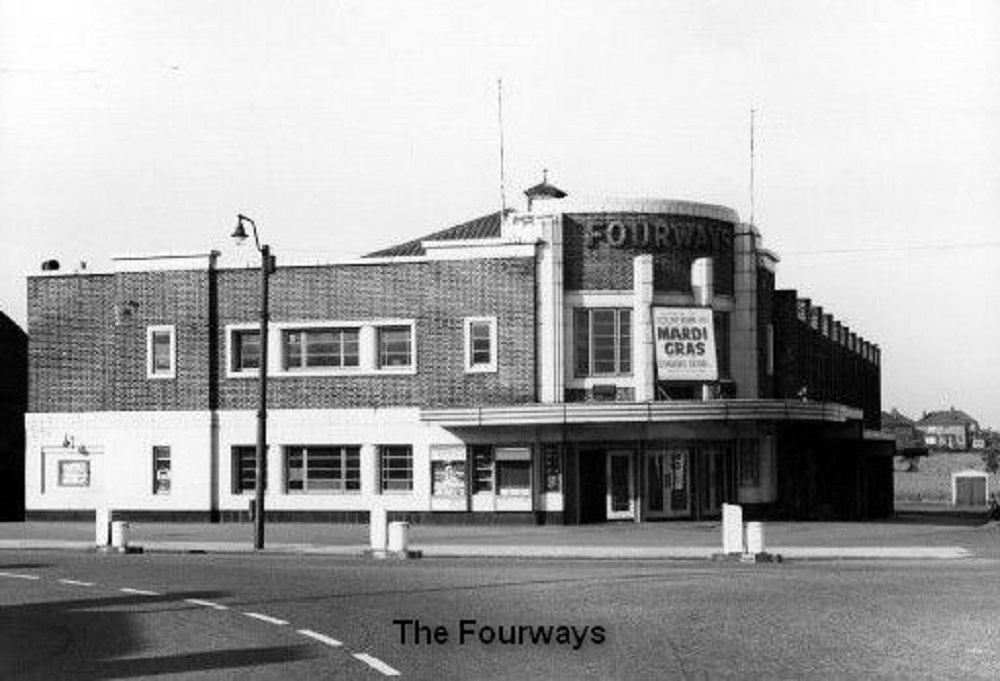

Strictly speaking, the MIP (or MIPP) was on Hartley Street, a few steps off the Lane. The 925 seat cinema opened its doors in 1920. 19 years later, just a few months before the outbreak of WW2, the Fourways became the Lane’s second cinema.

AVRO and Ferranti’ works were potential targets for the Luftwaffe. To protect their essential war production, four anti-aircraft guns were situated on Broadhurst playing fields.

Many of Moston’s houses lacked gardens, so the Lane’s air raid shelters were generally the indoor Morrison type, or back yard brick and reinforced concrete structures.

Post war

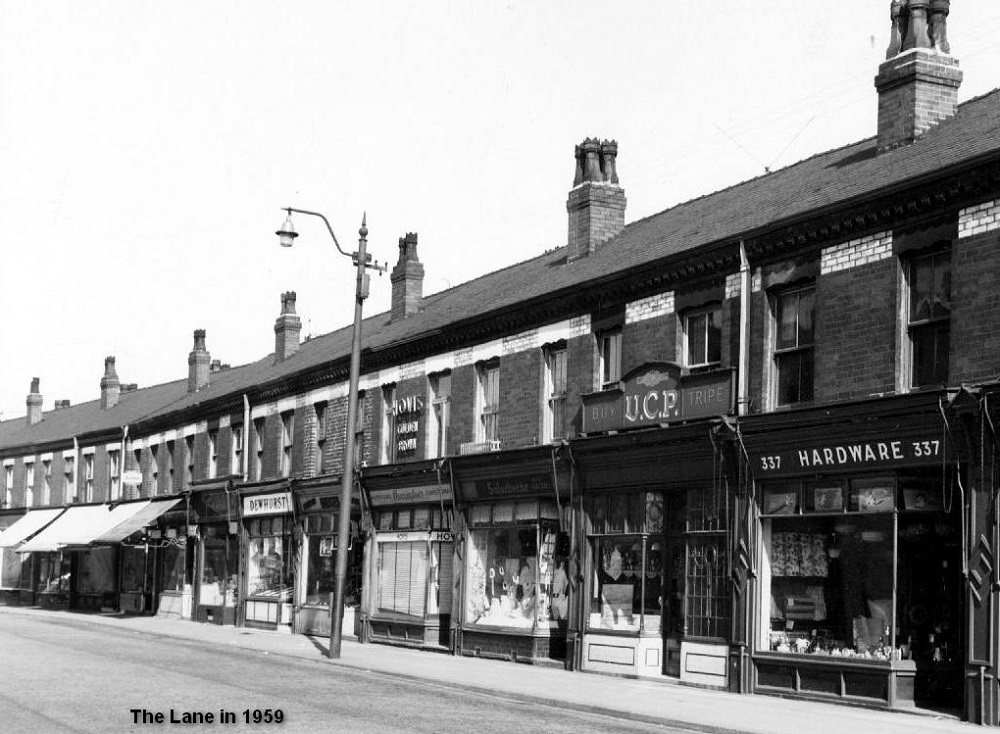

In school holidays, with no park nearby, a trip to the Lane was the best I could hope for. Our circuit started at Simpson Memorial, and while I dashed in to make a speedy library book exchange, Mum waited outside with my sister’s pram,

Fifties austerity must have left six-year-olds with simple expectations, because I recall being impressed by a shop window containing a currant cake, apparently baked in a fancy jelly mould.

And I enjoyed watching the endlessly revolving model of a foot and calf wearing a sheer nylon stocking, in the haberdasher’s window.

There was an Airfix model of the queen’s coronation coach in the toy shop. It added a touch of topicality to the display of smashing Chad Valley sets and the usual board games.

My absolute favourite shop window belonged to a hairdresser. With mirrors representing lakes, and dozens of the small glass animals popular at the time, someone had created a magical fantasy world which changed regularly enough to keep me going back time after time.

Before turning for home down Ashley Lane, there was one final stop to be made. I was just tall enough to see over the wall of the front garden of what I called the ‘gnome house’. There was a wishing well surrounded by ornamental woodland creatures and colourful gnomes.

If there had been the ‘best in Lane’ award, it should have gone to a shop with no window display to speak of. It was where my friends and I headed after our Saturday morning swim at Harpurhey Baths. Faint from hunger, we pooled the last of our coppers, and went into the little shop for a generously filled paper bag of broken biscuits to share on the way home. No biscuit has ever tasted as good since.

I used to travel home from school on the bus between the Ben Brierley and Gardeners Arms. On those journeys I first recall noticing there were some bits of Moston that seemed out of time amongst the urban sprawl.

Logically, I knew the Lane had ‘a past’, but where did Yeb Fold fit in? In those days, the cottages wouldn’t have looked out of place as an illustration in a book of country folklore. And how come in 1958, there was a herd of cows grazing in a field surrounded by modern semis, only a few feet from the bus window.

Curiosity led me on to discover ‘Billy Buttonhole’, a silk weaver living on the Lane in 1841 (see part 1). Strange to think that had he lived in the same place 100 years later, rather than weaving silk by hand, Billy might have been producing Lancaster bombers or radar at Ferranti’s.