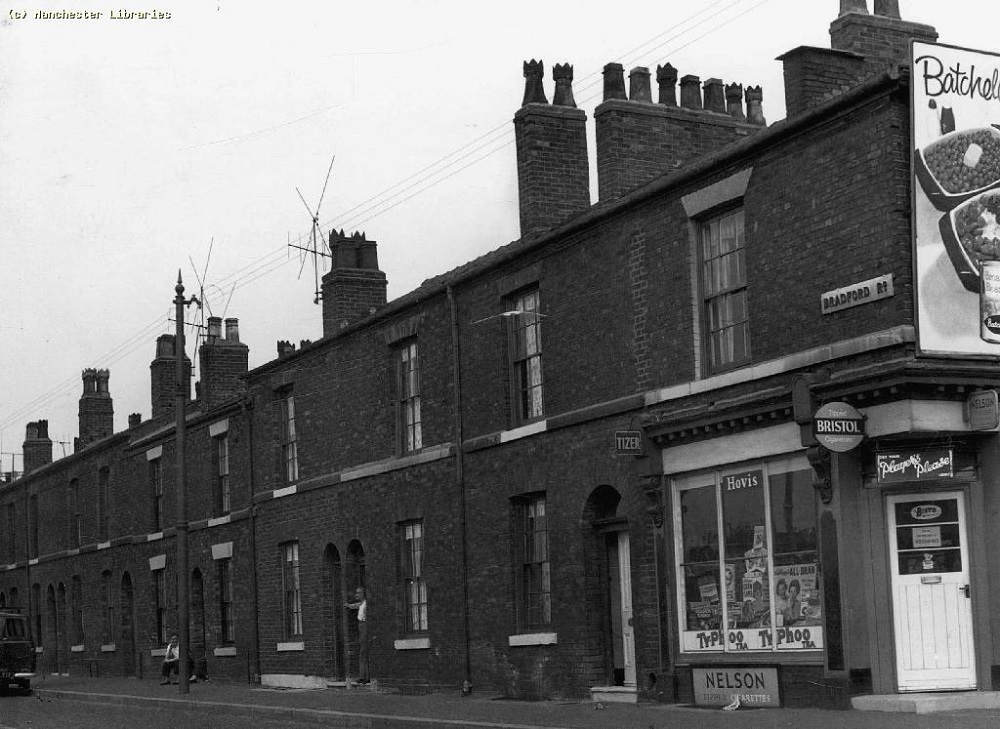

The built environment was a big factor in the games we played. For instance, ‘thunder and lightning’ or ‘knock and run’ was a torment particularly reserved for the residents of terraced houses – too much chance of getting spotted running away where there were gardens.

The terrace gable end was also a favoured spot to accommodate a couple of girls playing ‘two balls’ side by side. But the constant thump, thump of the balls was guaranteed to fetch out a large woman, typically wearing a wrap-around overall, who would bellow ‘go and play in your own street’. In the summer these same gable ends had cricket stumps chalked or painted on them. But when too many strikes from a ‘corkie’ thudded against the brickwork, the street cricketers received the same admonition from the flowery pinny brigade.

In the summer these same gable ends had cricket stumps chalked or painted on them. But when too many strikes from a ‘corkie’ thudded against the brickwork, the street cricketers received the same admonition from the flowery pinny brigade.

The council houses where I lived were built around two grassed areas we called ‘greens’. The road bisected them and on our side the green had a fine gravel path, ideal for bikes and scooters. The smooth surface around the other green was perfect for whip and top, and might account for why its popularity lasted so long with us.

Boys used ‘the greens’ for football and ‘split the kipper’, a game that was played with a penknife or other sharp blade. Flagged pavements were good for hopscotch and skipping where our preference was for a rope long enough to accommodate half a dozen girls.

Flagged pavements were good for hopscotch and skipping where our preference was for a rope long enough to accommodate half a dozen girls.

Some of the rhymes we chanted were a little out dated but stayed popular because their actions called for timing and agility. One such was ‘I’m an ATS girl dressed in green’. As far as I know, The ATS wore khaki but it didn’t bother us when we were touching the ground, turning around and doing ‘the kicks and splits’ which the rhyme dictated. Other rhymes featured film stars such as Betty Grable and Charlie Chaplin who were old hat by the 1950s. Our junior schools were single sex, so I suppose that was the reason girls and boys rarely played together. Marbles, or ‘alleys’ as we knew them, was a ‘mixed’ game, and we sometimes joined forces for chasing games such as ralivo, kick can or hide and seek. Firmly defined boundary restrictions were imposed to make sure the games didn’t go on indefinitely.

Our junior schools were single sex, so I suppose that was the reason girls and boys rarely played together. Marbles, or ‘alleys’ as we knew them, was a ‘mixed’ game, and we sometimes joined forces for chasing games such as ralivo, kick can or hide and seek. Firmly defined boundary restrictions were imposed to make sure the games didn’t go on indefinitely. Readers of The Perishers cartoon strip might recognise another mostly male activity which involved a vehicle the Daily Mirror called a carte. Variously called soapboxes or trolleys, in Manchester the homemade contraptions were known as bogies or guiders. These gravity racers required a sturdy wooden soap or apple box, old pram wheels or sometimes roller skates. The frame had a rope fixed to the ends of a steerable bar at the front.

Readers of The Perishers cartoon strip might recognise another mostly male activity which involved a vehicle the Daily Mirror called a carte. Variously called soapboxes or trolleys, in Manchester the homemade contraptions were known as bogies or guiders. These gravity racers required a sturdy wooden soap or apple box, old pram wheels or sometimes roller skates. The frame had a rope fixed to the ends of a steerable bar at the front.

Our fairly quiet street sloped down towards Church Lane which was a main road. Consequently Honister Road was adopted as an ad hoc race track where the idea was to perform a sharp right turn at the bottom. But only the most sophisticated vehicles had a brake. So to prevent the basic model guider from shooting out into the main road, a driver had to rely on a boot sole scuffed along the pavement. I don’t recall any fatalities, but I expect some poor car drivers lost years off their lives when a guider, travelling at high speed, shot across their bows after failing to make the turn.

I don’t recall any fatalities, but I expect some poor car drivers lost years off their lives when a guider, travelling at high speed, shot across their bows after failing to make the turn.

Boys and girls both created dens. Ours were for playing ‘house’ or ‘shop’ while the sole purpose of a boy’s den seemed to be a secluded place where they could build a fire.

‘Den’ was also the word for the base in a game of hide and seek or similar. We called out ‘bounce’ or ‘kickstone 1 2 3’, to signal getting back without capture. I can’t recall the Moston word chasers used when someone’s hiding place was spotted, but according to my mother it was ‘whip’ in Collyhurst. In a chasing game, a halt for a loose shoelace or ‘stitch’ was achieved with a cry of ‘ballies’ while holding up both thumbs. Playing shop

Playing shop

When we moved to New Moston, our playground was the middle of three interlinked ‘frying pan’ cul-de-sacs. The narrowness of the roads and the almost complete absence of traffic lent itself to ‘Grandmother’s footsteps’, ‘What time is it Mr. Wolf?’ and ‘Farmer, farmer may I cross your golden river?’ – games not usually played in Moston’s streets.

There were also seasonal factors to some of our games. Conkers or sticky bud (burdock) fights were autumnal, and snowballing and sliding obviously required a good freeze. On dark winter nights we raided the wood stocks other kids had assiduously ‘logged’ for their own bonfire. But natural seasons aside, how did we know when to make the change from skipping to hopscotch? If there was some mysterious formula, I was never in on the secret.

The shop’s attraction was that while the front window displayed packets of dried peas, Kingpin flour and custard powder, the side window was a child’s box of delights. Standing outside discussing what we should choose was almost as enjoyable as the sweets themselves.

The shop’s attraction was that while the front window displayed packets of dried peas, Kingpin flour and custard powder, the side window was a child’s box of delights. Standing outside discussing what we should choose was almost as enjoyable as the sweets themselves. Photo compliments of Brian Winstanley

Photo compliments of Brian Winstanley Photo of J Burgon’s horse drawn ice cream cart (with the kind permission of Mr Ray Boggiano)

Photo of J Burgon’s horse drawn ice cream cart (with the kind permission of Mr Ray Boggiano) The old township districts were rightly proud of their Sunday schools. From 1784, they had been offering free education to poor children and adults. And until child labour was abolished altogether, Sunday school superintendents and teachers were in the forefront of the battle to achieve safer and healthier working conditions for their scholars.

The old township districts were rightly proud of their Sunday schools. From 1784, they had been offering free education to poor children and adults. And until child labour was abolished altogether, Sunday school superintendents and teachers were in the forefront of the battle to achieve safer and healthier working conditions for their scholars. The dresses girls walked in were showy, but totally impractical for the often damp and chilly Manchester weather. But even when they became available, it was an indulgent parent who allowed a plastic mac to cover up those swanky new clothes for anything less than a torrential down-pour.

The dresses girls walked in were showy, but totally impractical for the often damp and chilly Manchester weather. But even when they became available, it was an indulgent parent who allowed a plastic mac to cover up those swanky new clothes for anything less than a torrential down-pour. Boys were grouped into uniformed, grey-shorted or even sailor-suited lines. They mostly walked in single file, sometimes holding on to a fancy cord; woe betide any scholar who didn’t maintain the required distance between themselves and the next child.

Boys were grouped into uniformed, grey-shorted or even sailor-suited lines. They mostly walked in single file, sometimes holding on to a fancy cord; woe betide any scholar who didn’t maintain the required distance between themselves and the next child.