My old headmistress insisted on calling cinemas ‘picture palaces’. The Adelphi’s art deco style certainly made it seem more palatial than the two other cinemas within walking distance (see ‘Flicks in Moston‘ by Alan Hampson).

The Adelphi matinee cost 6d, and inside the cinema, lollies were 3d. The shop opposite sold them for 1d, which left tuppence for sweets – well worth the inconvenience of sticky ice-melt running down your sleeve as you frantically sucked the lolly while queuing to go in.

The harassed looking Adelphi commissionaire had a moustache and withered arm. Wearing a uniform more appropriate to a Ruritanian operetta, the poor man was expected to keep control of a bunch of rowdy kids. But once inside, he got his own back on his lolly-stained charges.

The Adelphi was quite large and far from full on Saturday afternoons. Yet the commissionaire insisted we fill the front seats before letting us start on the second row, and so on. Only the late arrivals got to watch the screen without having their necks cricked back at an unnatural angle.

Not a discerning audience, we would watch anything so long as there was a picture and sound.

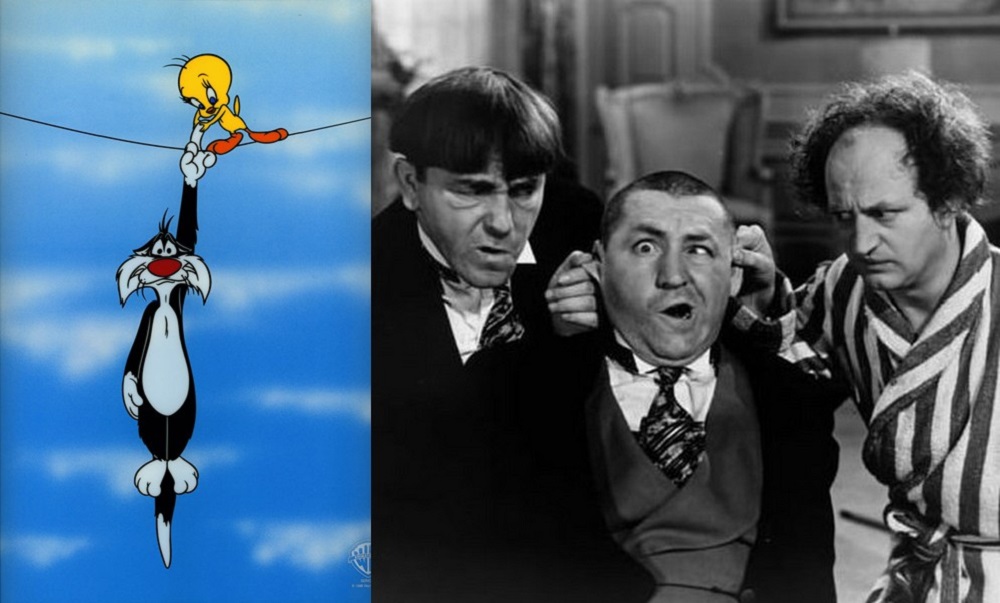

The usual programme contained a mixture of cartoons, cowboys, space fantasy and short comedy films. My personal favourite cartoon characters were Mr. Magoo, Tweetie Pie and Sylvester, which I preferred to Disney’s Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck.

When the nearest thing to ‘abroad’ was the Isle of Man, cinema acted as our ‘window on the world’, and we accepted what we saw there as real, or at least possible.

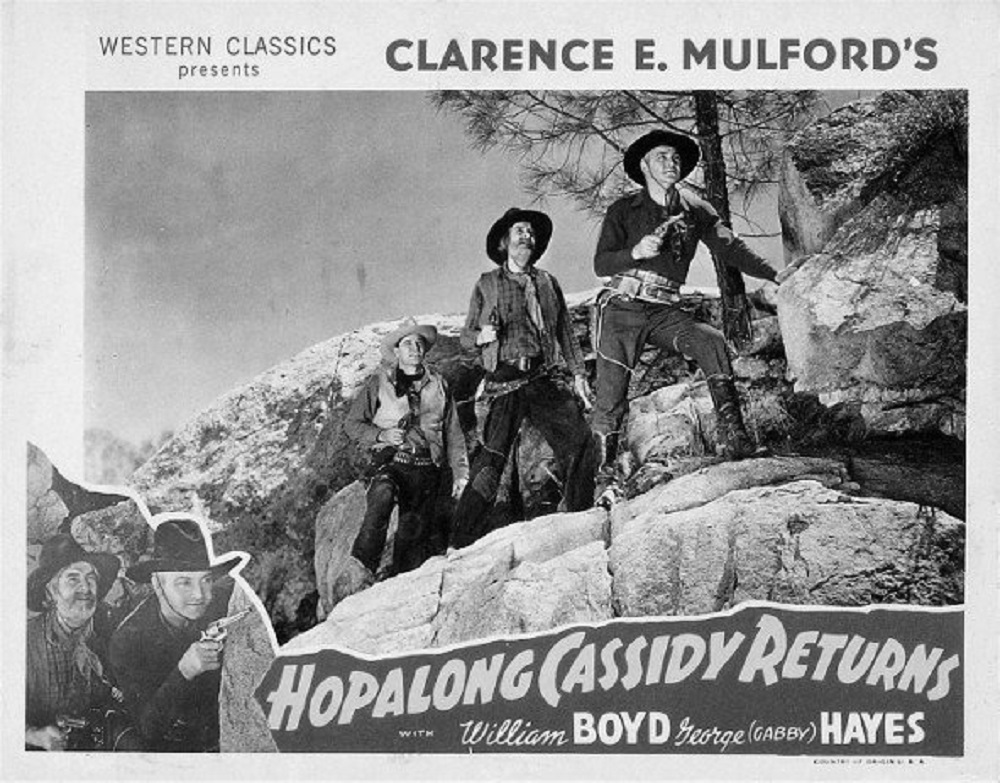

None of us believed in the futuristic spacemen who could both see and speak to earth from a rocket exploring the galaxy. At the same time, our credibility seemed flexible enough to accept the existence of a wild west with cowboys roping steers and shooting one another. The one implausible cowboy character was the rather rotund and misnamed Hopalong Cassidy, but I could certainly believe in his partner, Gabby Hayes.

Back then, thanks to cinema, Yanks were the ‘foreigners’ we knew most about. Kids might have been excused for thinking you would meet Amos and Andy, Our Gang, and the Three Stooges as you strolled down any US side-walk.

With that in mind, it struck me that my counterpart living in Manchester, New Hampshire, might have had an equally strange view of the British. Would she expect to encounter Sherlock Holmes, wearing his trademark Ulster and deerstalker, as he hunted for the Blue Carbuncle in a swirling ‘London particular’?

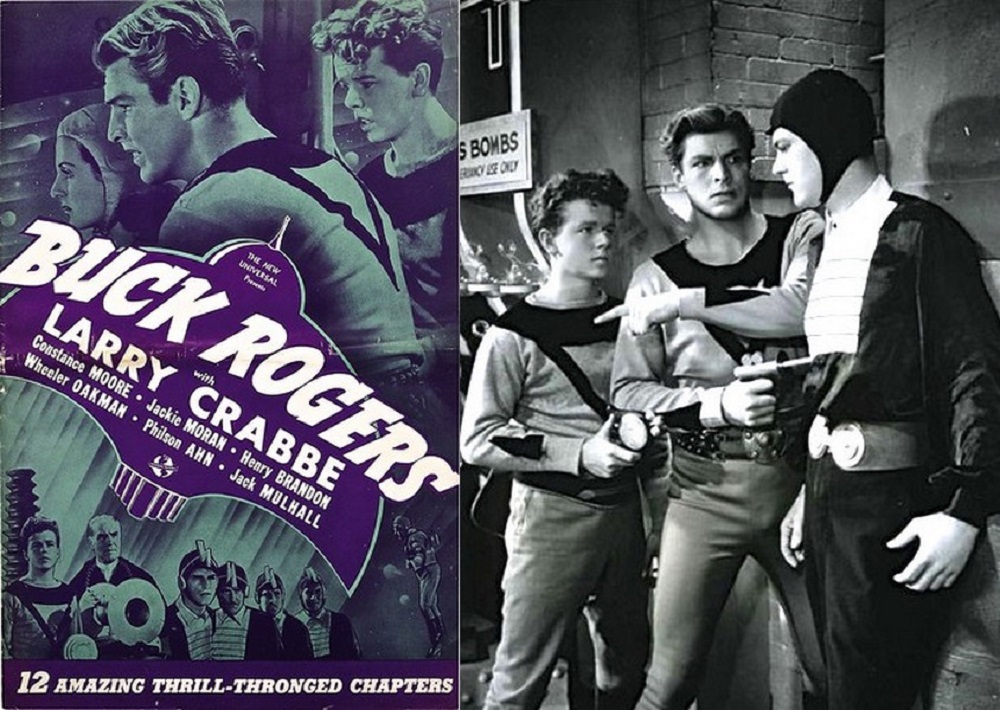

The final item in the matinee was always a serial, which concluded with the words ‘don’t miss Next week’s thrilling episode’. Virtually every serial featured the same outcrop of rock in the same desert, with little variation in plot.

Typically, a hero (often a cowboy) set out to right some grievous wrong. His adversary was sometimes masked but always dastardly and villainous. The two would be involved in a perilous chase, culminating in a thrilling ‘cliff hanger’.

Each week, with our very own eyes, we watched the stagecoach or motor car containing the hero plunging over the cliff edge. The following Saturday, the reprise showed the vehicle swerving away from the canyon’s edge in the nick of time. Discussing it on the way home, the miraculous escape was universally pronounced a ‘right swizz’.

Each serial had 12-15 parts, so practically nobody saw one all the way through. But come Monday, there was sure to be someone in the school yard willing to relate the thrilling climax (with actions for those who missed it on the previous Saturday).

Occasionally we got British ‘shorts’ featuring child actors such as Harry Fowler. One I recall was a gang of kids who decided to try window cleaning to get money to go hop-picking. They had no ladder, so had to design and build an ingenious device to do the upstairs windows. The film makers were obviously unaware that, to Mostoners, the idea of hop-picking was as foreign a concept as some of the things the ‘Our Gang’’ kids got up to.

Years later, I discovered there were such things as Junior Cinema clubs. I was miffed to have missed out on the badges, songs and yo-yo displays the ABC and Regal minors’ enjoyed.