Moston Brook is a 3.7 mile long tributary of the River Irk, and my family have lived close to it for four generations.

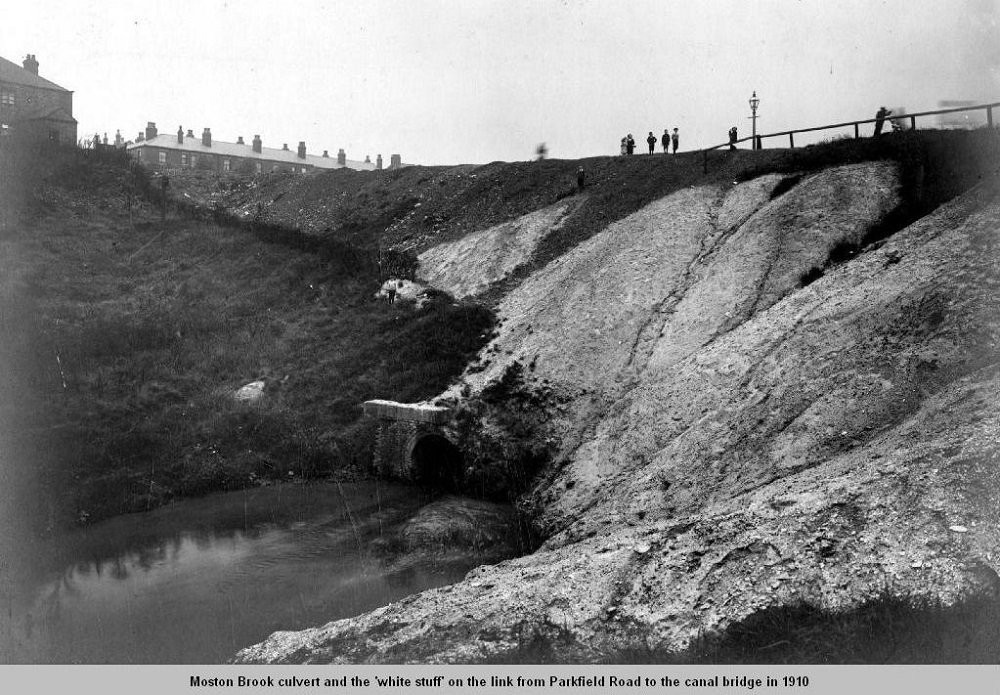

My mother grew up in a house built on top of one of the brook’s many culverts. After number 2 Culvert Street was scheduled for demolition, the family moved to a road off Church Lane in Moston, where the brook then still ran above ground.

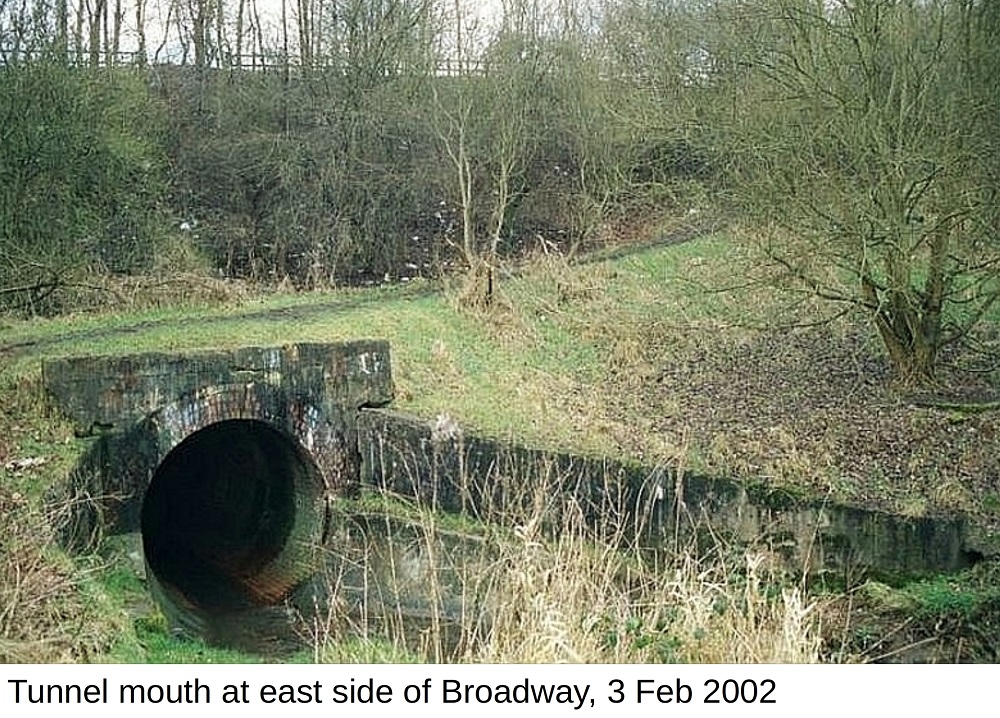

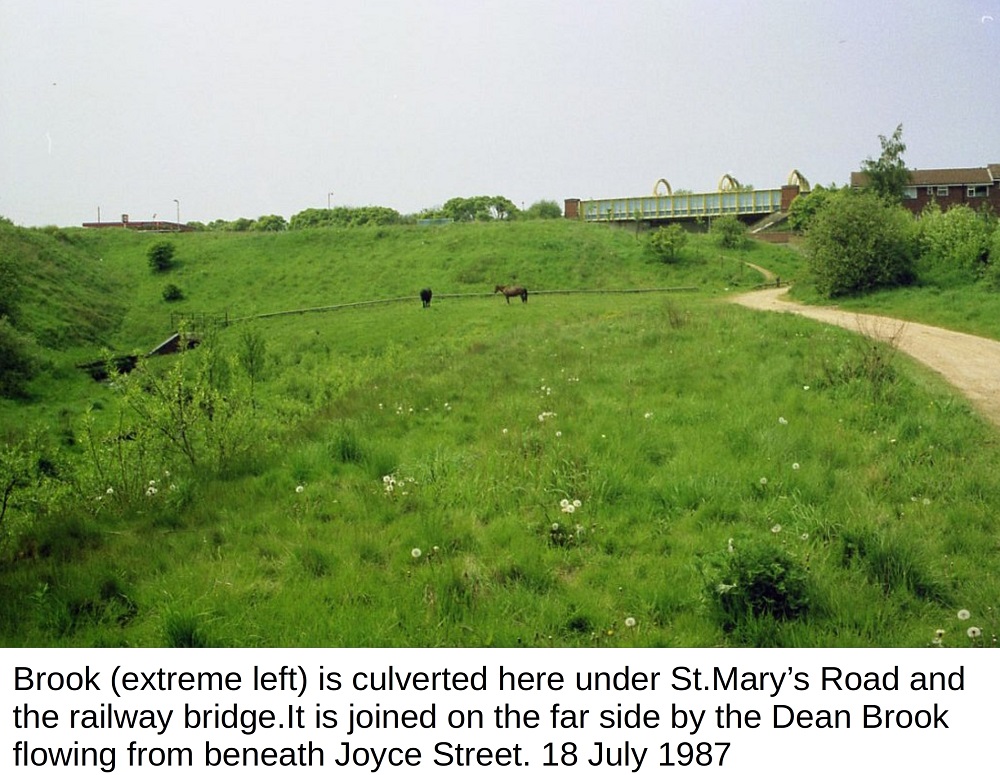

When I was 9 we moved from my grandparent’s house to New Moston and a couple of minutes walk took you to the Brook. Where it ran under Broadway, I was fascinated to find sprinklers spraying water on slag heaps. Our belief was that they prevented the re-ignition of smouldering coal from a fire in the disused Moston pit. Although the tale seems to be apocryphal, it does illustrate the brook’s close connection to the area’s industrial history.

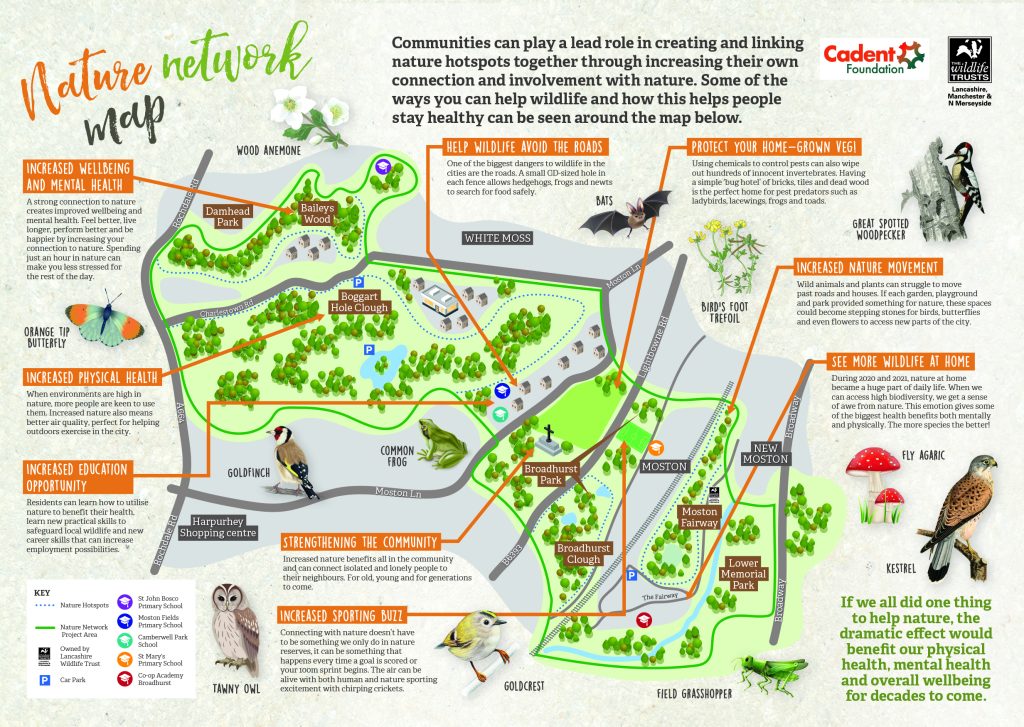

From its beginning in Chadderton/Failsworth, Moston or Morris Brook flows through Moston, Harpurhey and Collyhurst before reaching the River Irk.

Due to the coal and coke waste from industrial processes nearby, the stretch of water running alongside Church Lane was known as the Black Brook. In the terrible winter of 1947, local people picked waste coke/coal from the Black Brook to supplement their fuel ration. So much culverting had taken place that the scavengers didn’t realise the water was the Moston Brook.

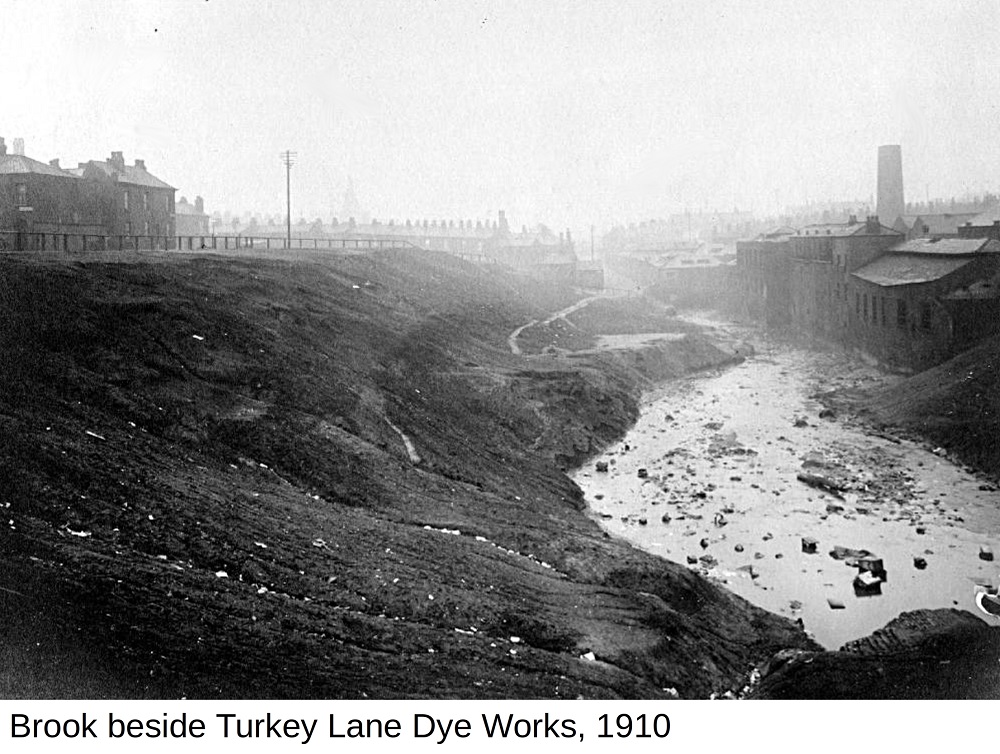

Manufacturers who were at the forefront of industrialisation were quick to realise the brook’s potential. Some of the first industries to exploit it as a water supply were dyers and finishers of textiles, closely followed by coal and clay extraction.

The names of terraced streets springing up around the brook, soon began to reflect aspects of the industries nearby. For instance, Turkey Lane was named for the first colour fast, true red dye used on yarn and cloth. Angel Delaunay wasone of the pioneers who developed Turkey red dye in England. Delaunay’s Road in Blackley bears his name to this day.

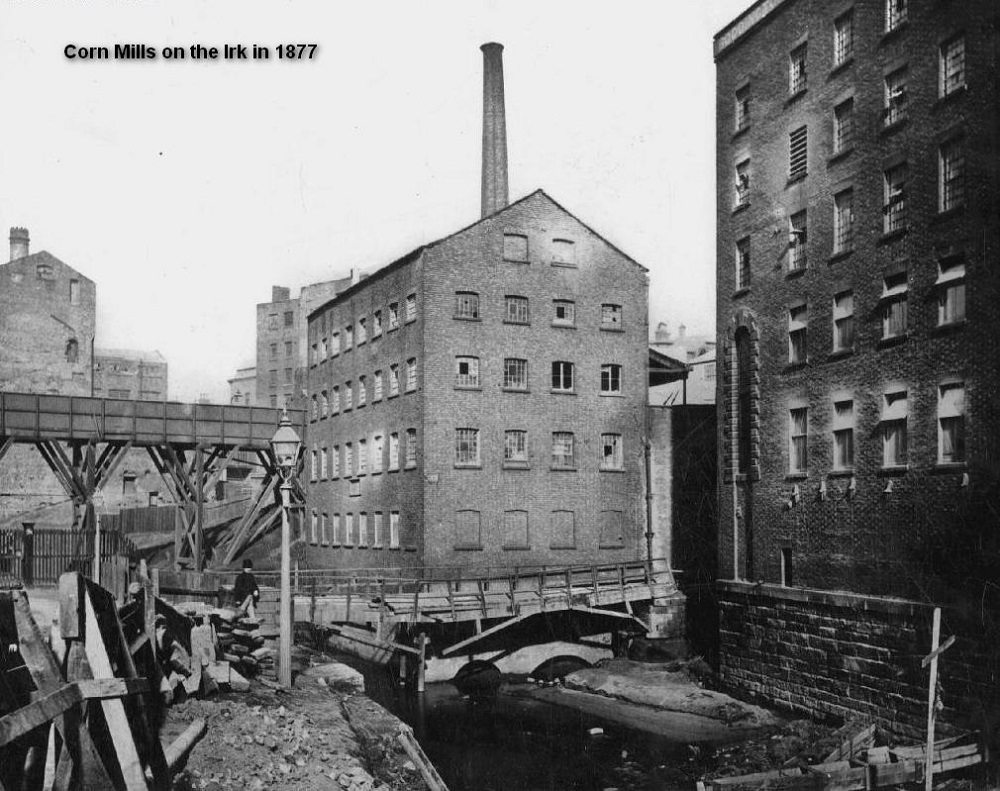

It was inevitable that mills, pits and ‘diggies’ would utilize the brook as a means of disposal for the waste they created.

A late 18th century gazetteer described Collyhurst as ‘picturesque, with wooded slopes running down to the River Irk’. The brook ran through this pastoral idyll, but soon it would be changed by the Turkey Red dye, bleach from cotton finishing and black from the logwood rasping mills.

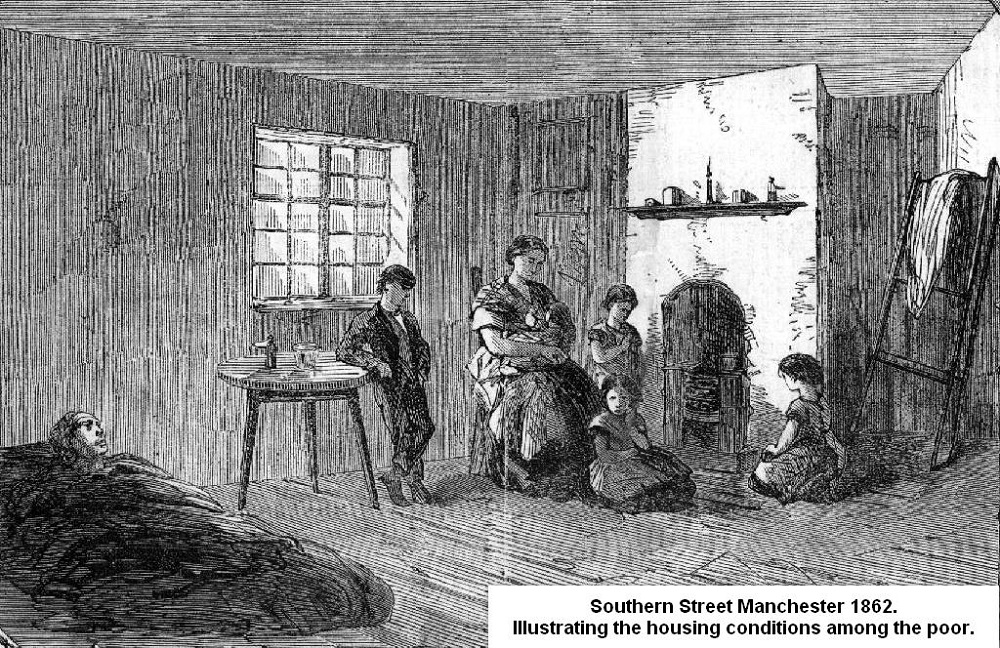

By 1838, the gazetteer’s wooded slopes had been replaced by the courts and alleys inhabited by a population of 38,000. These dwellings were mostly hastily built without access to a clean water supply or any regard for the disposal of sewage. As a result, the unculverted sections of the Brook became a repository for all manner of organic material. This cocktail of industrial waste and domestic refuse was carried by the brook until it merged with the toxic effluent discharged into the Irk by tanneries, boneyards, gas and ammonia works.

Conditions for the poor in Manchester were at their very worst when the 1832 cholera pandemic swept the world. Medical science was more inclined to attribute cholera to bad air (sometimes called miasma) than poor sanitation. It was only later that bacteria in untreated sewage was discovered to be the real culprit. Unsurprisingly, the deadly disease visited many families living in Collyhurst’s overcrowded courts bordering the Irk.

Henry Gaulter, a Manchester doctor, embarked on a mission to discover how cholera was spread. Disregarding the personal danger, the doctor set out to inspect the streets and houses of the very poorest. He entered their homes with questions about their previous illnesses, their occupations and the food they ate.

Even though the cause of cholera eluded Dr. Gaulter, his researches have left us a unique eye witness account of the depravation and hardship Manchester’s workers endured in their everyday life. Of the township itself, Gaulter reported, ‘In the greater part of Manchester there are no sewers at all. And, where they do exist, they are so small and badly constructed that instead of contributing to the purification of the town, they become themselves nuisances of the worst description’.

Soap and offal boiling , as well as the dressing of hides, were classed as ‘nuisances’ in bye-laws. However the authorities did little or nothing to prevent the waste from such processes being discharged into the river, along with untreated sewage.

One of the most infamous outbreaks of disease occurred in Allen’s Court which, due to its high death rate, became known as Cholera Court. According to Dr. Gaulter, Allen’s Court was populated by ‘decent and reputable silk weavers’. Regardless of their respectability, he described where they lived as ‘..a tripe boiler’s works are on one side of the court. A catgut manufactory on the other: in front is the Irk flowing close under the houses, dyed and defiled by impurities of every kind.… A sewer runs above ground…. A bone boiler has his place a little higher up, and it was said that he had just thrown several tons of rotten salmon into the river’.

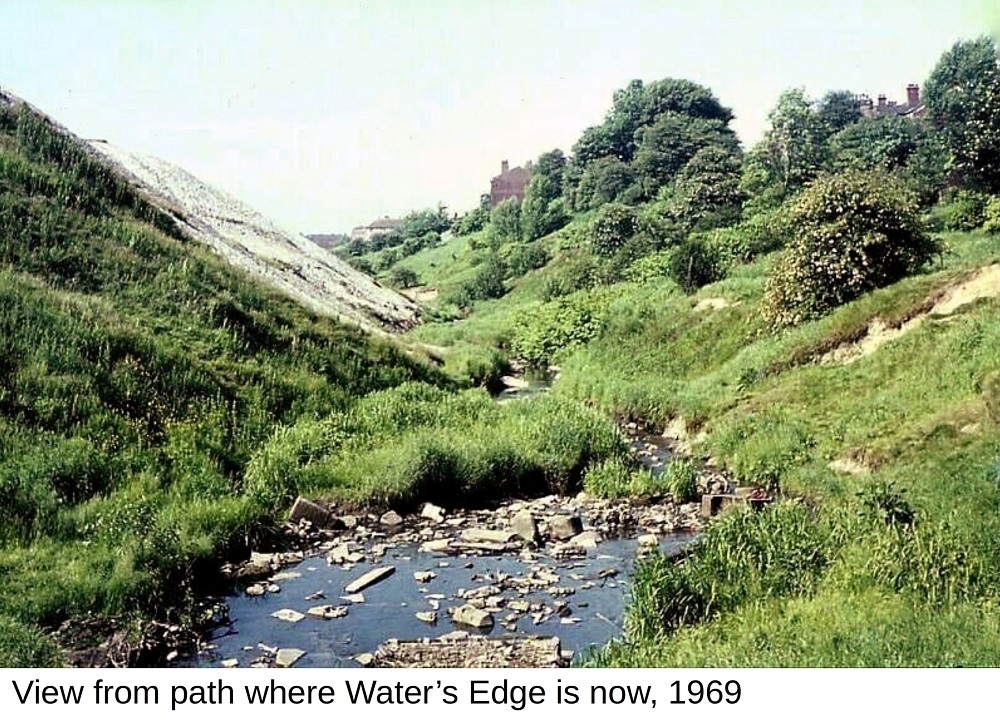

Conditions in and around the brook were much improved in the 120 years since the cholera epidemic. Nevertheless, we kids were told you could catch ‘the fever’ from playing near the brook. For 30 years we lived in a house on Belgrave Road where the Brook ran along the boundary of the back garden. During that time, the ‘white stuff’ was grassed over and the slag heaps disappeared. But my children grew up never knowing what colour the brook would run from one day to the next.

Today, this once unlovely repository of industrial waste has been transformed. It is now a woodland corridor providing a haven for wildlife, as well as flower and tree species. And the formerly toxic River Irk described by Henry Gaulter, once again supports fish.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to all the people whose amazing vision and hard work has created an amenity providing so much pleasure for those of us who have discovered its delights.