In the 1950s it was a child’s lot to run errands. The early years spent with mum or nan was a sort of apprenticeship for shopping alone. Soon you would be in a position to say what number you wanted the bacon sliced on, or whether custard creams were an acceptable substitute when they were out of gingers. Moston had its specialist shops but almost every street corner had an ‘Open All Hours’ type store, selling everything from Butter Puffs to mothballs and face powder. The one we used had formerly been a terraced house. There was no display window and the door was in the blank gable end wall. On entering, it was bundled firewood stacked under the staircase that first attracted the eye.

Moston had its specialist shops but almost every street corner had an ‘Open All Hours’ type store, selling everything from Butter Puffs to mothballs and face powder. The one we used had formerly been a terraced house. There was no display window and the door was in the blank gable end wall. On entering, it was bundled firewood stacked under the staircase that first attracted the eye.

The former living room had an L-shaped counter, fronting shelves stacked high with goods. But today’s shopper would be confounded by the lack of choice. Two kinds of bacon were available, middle and rody (streaky) and two kinds of cheese – Cheshire that we bought and Cheddar which we didn’t.

In the queuing area, there was a display unit of deep, glass-topped biscuit tins. These had to be passed across the shoulders of customers for the biscuits to be weighed and bagged up. Roast ham was expertly carved with a long bladed knife, but bacon was sliced to the selected thickness on a hand turned bacon slicer. Because we kept chickens in the back garden, I escaped the potential pitfalls of carrying home a paper bag full of eggs.

It was dinned into the young that even when well wrapped in newspaper, firelighters and soap powder must be kept separate from food stuffs.

If there was no (mechanical) cash register, our purchases were tallied up in pencil on a paper bag, and totalled at lightning speed – no mean achievement in pre-decimal days. On Ashley Lane there was a chemist, baker, newsagent, butcher, and green-grocer who also sold wet fish. Vegetables came loose and unwashed, necessitating a dedicated ‘potato bag’. Ours was made of rexine, an artificial leather-cloth produced by a company in Hyde. As a boy, my father once forgot the all-important bag, and was told to hold out his gansey (sweater). He did so, and 5 lbs of King Edwards were unceremoniously tipped into it.

On Ashley Lane there was a chemist, baker, newsagent, butcher, and green-grocer who also sold wet fish. Vegetables came loose and unwashed, necessitating a dedicated ‘potato bag’. Ours was made of rexine, an artificial leather-cloth produced by a company in Hyde. As a boy, my father once forgot the all-important bag, and was told to hold out his gansey (sweater). He did so, and 5 lbs of King Edwards were unceremoniously tipped into it.

As the bakers only provided paper bags and tissue paper, it was advisable to take a wicker basket or straw shopping bag for pies, hot bread and iced fancies to stay intact. To get your pies, the ritual was to pay an assistant who would then pencil in a series of mysterious symbols on the ubiquitous paper bag, before placing it at the bottom of the pile. Every eye in the queue was fixed on that stack of bags to make sure they remained in strict order.

The bakehouse was on the opposite side of the road, so pies arrived straight from oven to shop, on the head of a man carrying several wooden trays covered in a cloth. When he was spotted, a ripple ran through the queue and I prayed the current batch wouldn’t run out before the bag with our order came to the top of the stack.

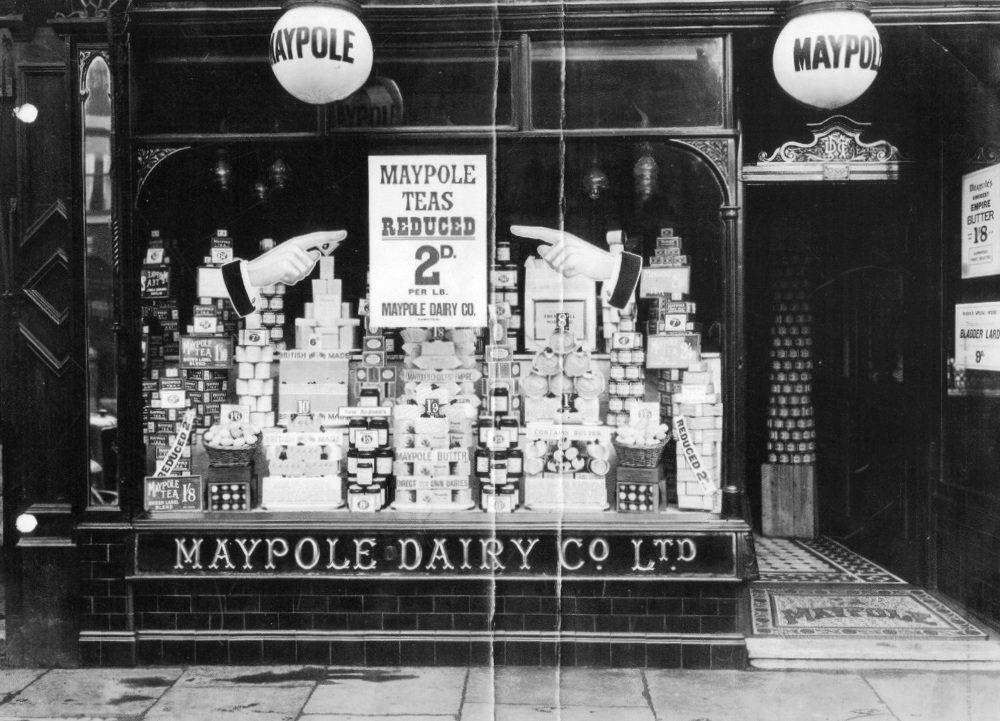

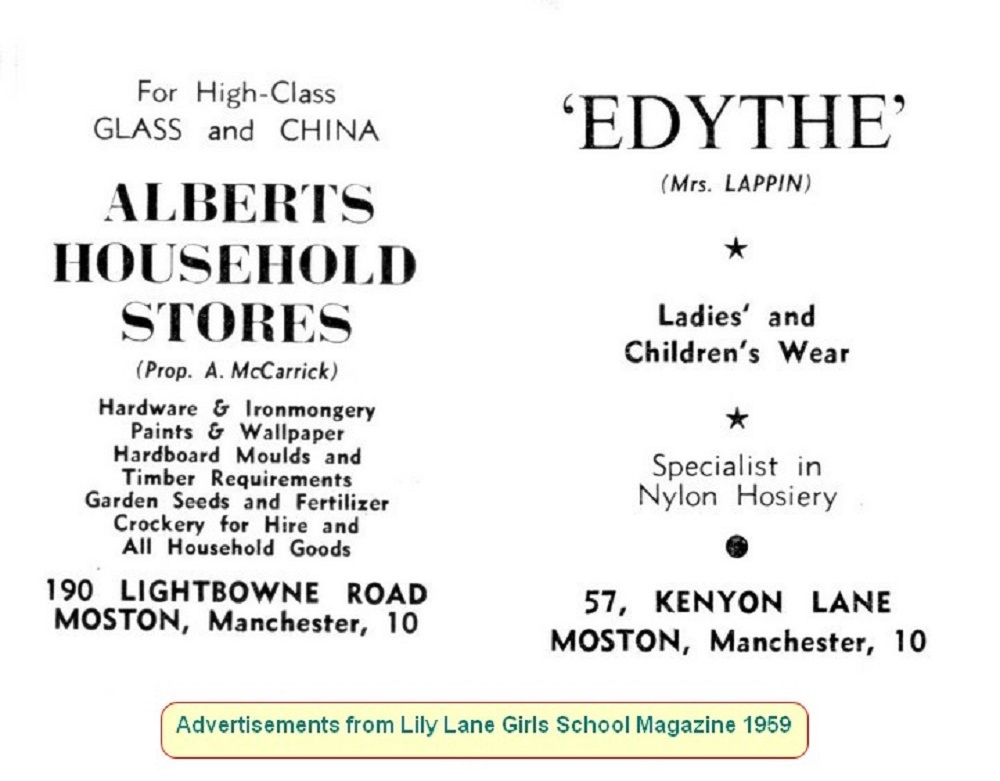

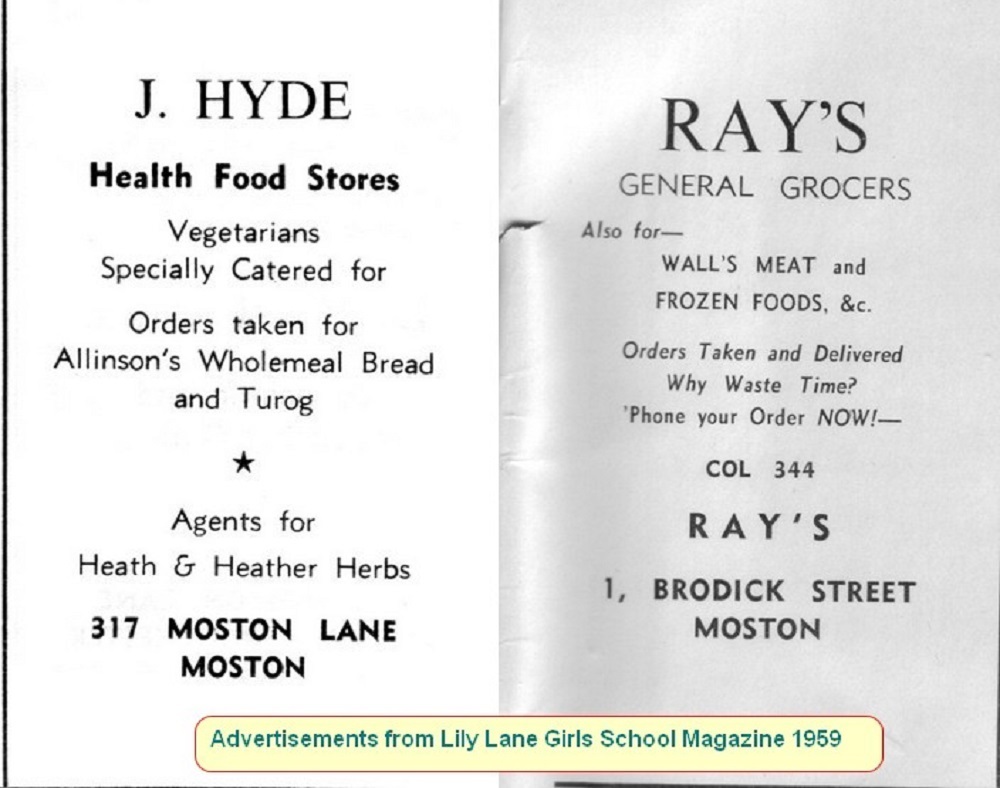

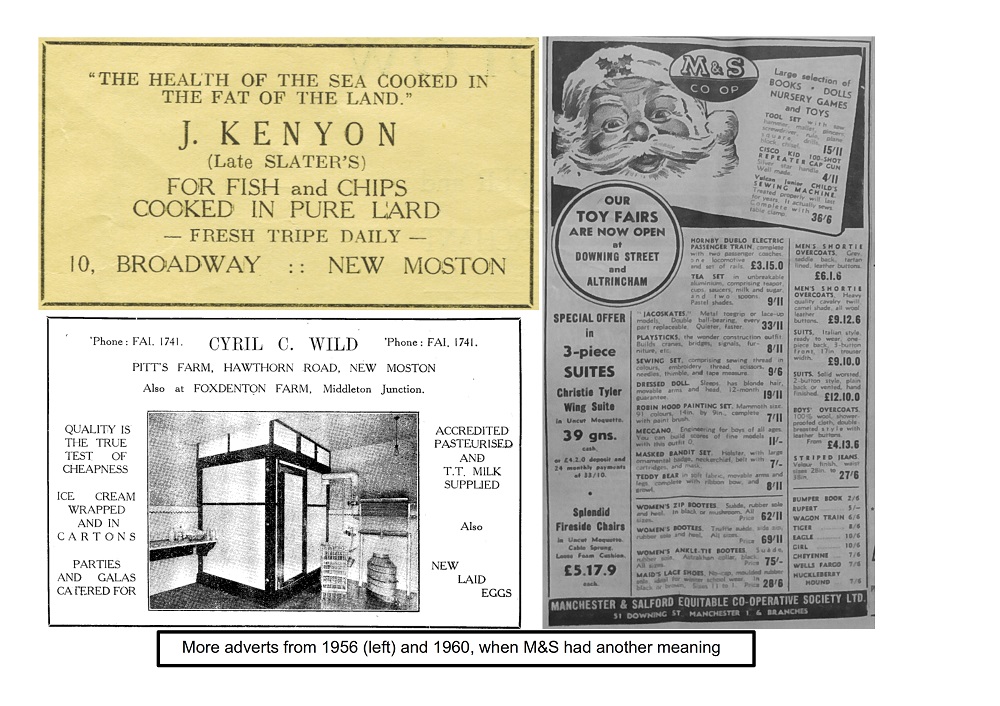

Within easy walking distance, we had a chip shop, ironmongers and Post Office. If Mr Barratt was serving, going to the chippie was definitely my favourite errand. He would always wrap a small piece of white paper around a couple of fat chips to be eaten on the way home. Saturday was the day for ‘the lane’. The shops on Moston Lane were there to supply all our needs from cradle to grave. There was the Maypole grocers, shoe shops, drapers, dry cleaners, and yes, even an undertaker.

Saturday was the day for ‘the lane’. The shops on Moston Lane were there to supply all our needs from cradle to grave. There was the Maypole grocers, shoe shops, drapers, dry cleaners, and yes, even an undertaker.

In 1956 we moved to New Moston and became enthusiastic members of the FIS Co-op. My sister served her shopping apprenticeship at their Broadway stores. The large grocers had various ‘departments’ with separate counters. As each had its own queue, the trick was to send a child to the longest to keep a place for mum while she got served at a shorter one.

If you went an errand alone, the mantra was ‘don’t forget the divvy (dividend) number’. For each transaction, the amount spent along with your number was written on a perforated paper counterfoil. The shop kept a carbon copy, and after a specified time, the total amount spent was added up and a percentage annual dividend paid out. Divvy money often went toward Christmas luxuries, so that all important number needed to be etched on your brain. To my mind, supermarkets will never replace the convenience of nipping round the corner for a bottle of Camp coffee, OK Sauce or a roll of Izal, which when not performing its primary purpose, made excellent tracing paper or a comb kazoo.

To my mind, supermarkets will never replace the convenience of nipping round the corner for a bottle of Camp coffee, OK Sauce or a roll of Izal, which when not performing its primary purpose, made excellent tracing paper or a comb kazoo.

Buildings were created by sliding the modular brick tiles, windows and doors between metal rods inserted into a base. The only down side was that our creations had to be dismantled when the table was needed for meals.

Buildings were created by sliding the modular brick tiles, windows and doors between metal rods inserted into a base. The only down side was that our creations had to be dismantled when the table was needed for meals. Kids used to being feral soon tired of sedentary pastimes and brought scaled-down versions of outdoor games inside. In true wartime ‘make do and mend’ style we used our family’s laundry basket, a wooden crate with sturdy rope handles which normally lived under the kitchen table. On rainy days it could be transformed into a pirate ship or stagecoach under attack from ‘red Indians’, or anything else our imagination conjured up.

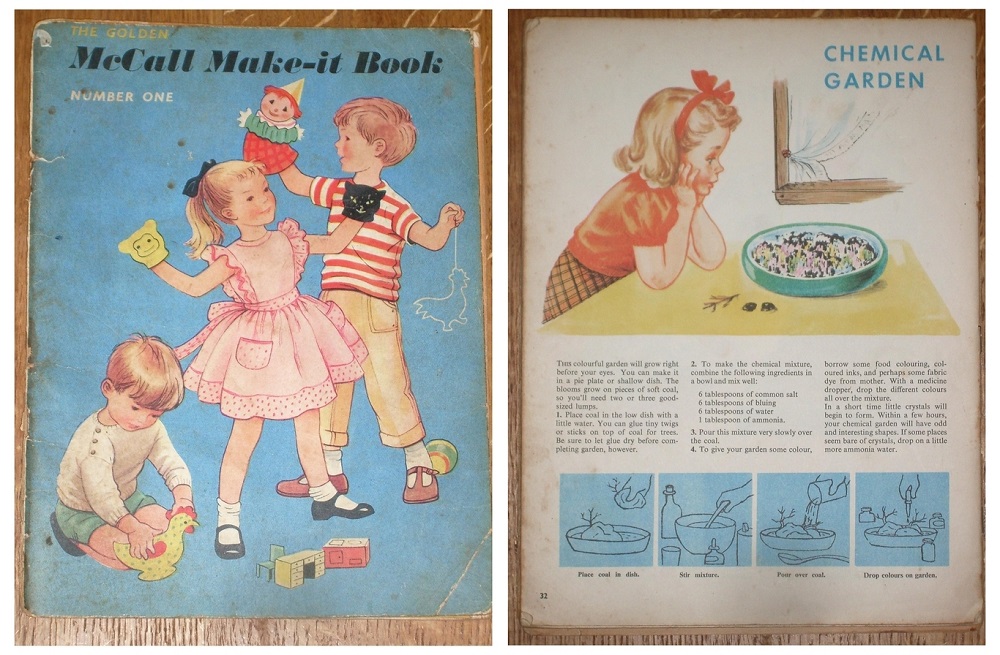

Kids used to being feral soon tired of sedentary pastimes and brought scaled-down versions of outdoor games inside. In true wartime ‘make do and mend’ style we used our family’s laundry basket, a wooden crate with sturdy rope handles which normally lived under the kitchen table. On rainy days it could be transformed into a pirate ship or stagecoach under attack from ‘red Indians’, or anything else our imagination conjured up. Time and patience was required for the fiddly cutting out in those pre-sellotape days, when a slip of the scissors could spell disaster. The figures came printed on thin card and the paper outfits had small tabs which folded around the doll to keep them in place. My sister and I often combined forces to act out plays with our dolls as the characters.

Time and patience was required for the fiddly cutting out in those pre-sellotape days, when a slip of the scissors could spell disaster. The figures came printed on thin card and the paper outfits had small tabs which folded around the doll to keep them in place. My sister and I often combined forces to act out plays with our dolls as the characters. In the summer these same gable ends had cricket stumps chalked or painted on them. But when too many strikes from a ‘corkie’ thudded against the brickwork, the street cricketers received the same admonition from the flowery pinny brigade.

In the summer these same gable ends had cricket stumps chalked or painted on them. But when too many strikes from a ‘corkie’ thudded against the brickwork, the street cricketers received the same admonition from the flowery pinny brigade. Flagged pavements were good for hopscotch and skipping where our preference was for a rope long enough to accommodate half a dozen girls.

Flagged pavements were good for hopscotch and skipping where our preference was for a rope long enough to accommodate half a dozen girls. Our junior schools were single sex, so I suppose that was the reason girls and boys rarely played together. Marbles, or ‘alleys’ as we knew them, was a ‘mixed’ game, and we sometimes joined forces for chasing games such as ralivo, kick can or hide and seek. Firmly defined boundary restrictions were imposed to make sure the games didn’t go on indefinitely.

Our junior schools were single sex, so I suppose that was the reason girls and boys rarely played together. Marbles, or ‘alleys’ as we knew them, was a ‘mixed’ game, and we sometimes joined forces for chasing games such as ralivo, kick can or hide and seek. Firmly defined boundary restrictions were imposed to make sure the games didn’t go on indefinitely. Readers of The Perishers cartoon strip might recognise another mostly male activity which involved a vehicle the Daily Mirror called a carte. Variously called soapboxes or trolleys, in Manchester the homemade contraptions were known as bogies or guiders. These gravity racers required a sturdy wooden soap or apple box, old pram wheels or sometimes roller skates. The frame had a rope fixed to the ends of a steerable bar at the front.

Readers of The Perishers cartoon strip might recognise another mostly male activity which involved a vehicle the Daily Mirror called a carte. Variously called soapboxes or trolleys, in Manchester the homemade contraptions were known as bogies or guiders. These gravity racers required a sturdy wooden soap or apple box, old pram wheels or sometimes roller skates. The frame had a rope fixed to the ends of a steerable bar at the front. I don’t recall any fatalities, but I expect some poor car drivers lost years off their lives when a guider, travelling at high speed, shot across their bows after failing to make the turn.

I don’t recall any fatalities, but I expect some poor car drivers lost years off their lives when a guider, travelling at high speed, shot across their bows after failing to make the turn. Playing shop

Playing shop