Patchy, because some epochs of this building’s past are lost in obscurity, and because in its present state it is in dire need of patching up.

If you are unfamiliar with its name, you are probably not alone; many Moston residents pass by Hough Hall Road, next to Moston Lane Primary School, and barely glance at the rather ramshackle building just behind it.

Yet this is a real piece of history, right on our doorstep. Given its age and sometimes unsympathetic usage, it is a remarkable survival.

Sketch of Hough Hall as it appeared in the 1850s

Sketch of Hough Hall as it appeared in the 1850s

Almost certainly from the late Elizabethan period or earlier, the first documented reference to this hall is in an inventory of Robert Halgh (variously spelt Halghe or Hough) dated 1591, although the estate was considerably older. Though it is not certain that the building then was the same as the present one, it seems likely, given its general style and fittings.

The last of the line was another Robert, whose will was proven in 1685. Later owners included the Lightbownes, Minshulls, ‘Spanking’ Roger Aytoun and the Taylors, of Crofter’s Estate fame. Perhaps less well known is its subsequent history.

By 1838 it was held by farmer Thomas Thorp, a tenant of Samuel Taylor’s, and (typical of the period) was home both to Thorp’s family and his farm labourers. One of these, John Brundrett, had taken over the tenancy by 1850 and in 1851 it was stated to have 39 acres of land attached and “one house building” (possibly Hough House, on the opposite side of the road). Brundrett became the Poor Law Guardian for Moston the following year. Rear view of the hall from a newspaper clip in 1949

Rear view of the hall from a newspaper clip in 1949

In 1863, the tenancy passed to Mary Mills, whose sister Ann took over the following year and farmed there until 1876, the land by then having been reduced to 30 acres.

The hall was purchased outright in 1877 by Robert Ward of Manchester, tanner and manufacturer of moleskins, cords and velvets, who used it for his workshop. By 1881 he was living there himself, with his wife Sarah and children, while his brother (and business partner) James lived at Hough House.

Robert evidently dabbled in property, since in 1884 he was renting out a butcher’s shop on Ashley Lane. At some stage during his occupation, the house was enlarged by adding a third gable at the western end. It seems he also sold off the parcel of land on which Moston Lane County Primary School was built, opening in 1899. Photograph of the hall around 1900. Note the added side door and right-hand gable

Photograph of the hall around 1900. Note the added side door and right-hand gable

Robert died in February 1904, leaving the estate to his son John and daughters Elizabeth and Ann, but his widow Sarah and another daughter, Amy, continued living at the hall up to 1919.

In July 1921, the hall was sold to Dr. William Struthers Moore of Glasgow, who passed it on to Gerald Green, another medical practitioner, listed as resident from 1933 to 1939, and possibly longer. By 1944 it had been acquired by Eleanor Nesfield, a cosmetics manufacturer and distributor for Del Vost foundation cream. The hall seems to have served as house, office, works and warehouse. This company was advertised up to 1949, at least. Advertisement in the ‘Chemist and Druggist Supplement’ of 22 March 1947

Advertisement in the ‘Chemist and Druggist Supplement’ of 22 March 1947

The 1950s is another ‘patchy’ period, but the building changed hands again in March 1963, possibly to Peter Gobbi and John Leslie Clough, who were certainly there by 1968. These were brothers-in-law who ran a coal business from the premises and, in 1972, added further outbuildings behind the hall.

The rental from these offset the mortgage payments and gave space to other small businesses, such as CGC Services Ltd, car repairers. Later, Gobbi and Clough Ltd responded to changing fuel markets by selling bottled gas.

When the partners retired in 2003, it was sold to the present owner, who was resident until about 2016, but whose present circumstances are somewhat mysterious. Suffice to say the hall is currently lying semi-derelict, prey to urban explorers and vandals alike, and sadly becoming increasingly dilapidated. The hall today (2019)

The hall today (2019)

Since the 1940s, notably in 2005, there have been repeated attempts to find interested parties who could help preserve and restore Moston’s own ‘hidden gem’, but so far to no avail, despite a Grade II listing by English Heritage in 1974.

Having survived over 400 years of weather, wars and woodworm, what a crying shame it would be if it were lost now, through neglect.

— further reading —

The early history of the hall is well documented in A History of the Ancient Chapel of Blackley (Rev. John Booker, 1854) and in Fr. Brian Seale’s excellent book The Moston Story (1983).

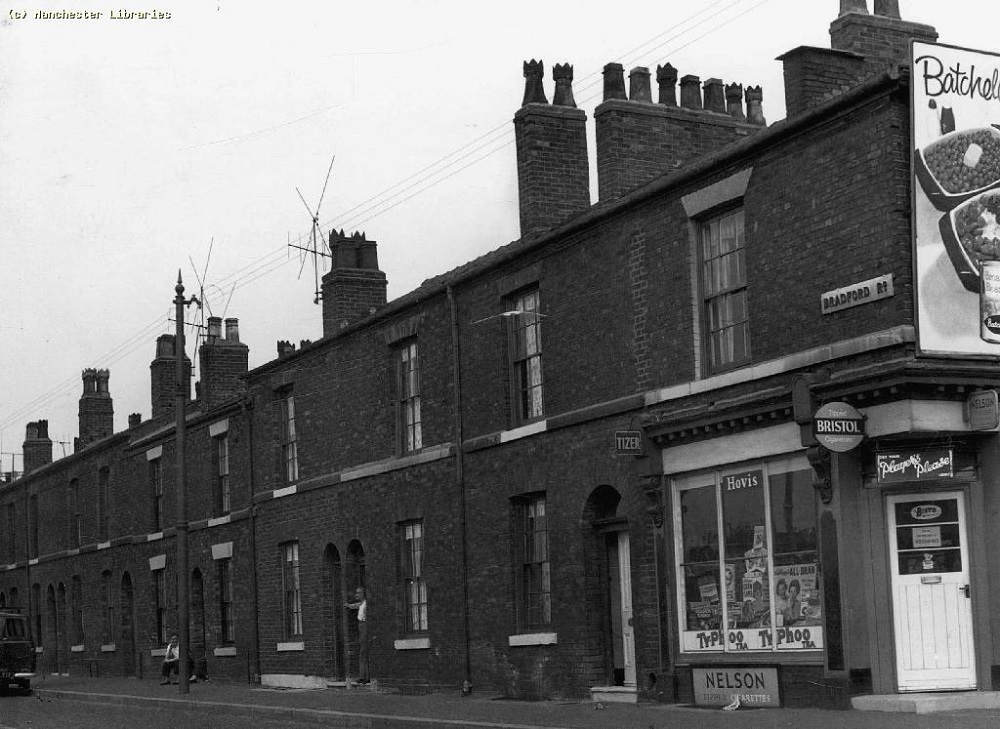

The shop’s attraction was that while the front window displayed packets of dried peas, Kingpin flour and custard powder, the side window was a child’s box of delights. Standing outside discussing what we should choose was almost as enjoyable as the sweets themselves.

The shop’s attraction was that while the front window displayed packets of dried peas, Kingpin flour and custard powder, the side window was a child’s box of delights. Standing outside discussing what we should choose was almost as enjoyable as the sweets themselves. Photo compliments of Brian Winstanley

Photo compliments of Brian Winstanley Photo of J Burgon’s horse drawn ice cream cart (with the kind permission of Mr Ray Boggiano)

Photo of J Burgon’s horse drawn ice cream cart (with the kind permission of Mr Ray Boggiano) The old township districts were rightly proud of their Sunday schools. From 1784, they had been offering free education to poor children and adults. And until child labour was abolished altogether, Sunday school superintendents and teachers were in the forefront of the battle to achieve safer and healthier working conditions for their scholars.

The old township districts were rightly proud of their Sunday schools. From 1784, they had been offering free education to poor children and adults. And until child labour was abolished altogether, Sunday school superintendents and teachers were in the forefront of the battle to achieve safer and healthier working conditions for their scholars. The dresses girls walked in were showy, but totally impractical for the often damp and chilly Manchester weather. But even when they became available, it was an indulgent parent who allowed a plastic mac to cover up those swanky new clothes for anything less than a torrential down-pour.

The dresses girls walked in were showy, but totally impractical for the often damp and chilly Manchester weather. But even when they became available, it was an indulgent parent who allowed a plastic mac to cover up those swanky new clothes for anything less than a torrential down-pour. Boys were grouped into uniformed, grey-shorted or even sailor-suited lines. They mostly walked in single file, sometimes holding on to a fancy cord; woe betide any scholar who didn’t maintain the required distance between themselves and the next child.

Boys were grouped into uniformed, grey-shorted or even sailor-suited lines. They mostly walked in single file, sometimes holding on to a fancy cord; woe betide any scholar who didn’t maintain the required distance between themselves and the next child.