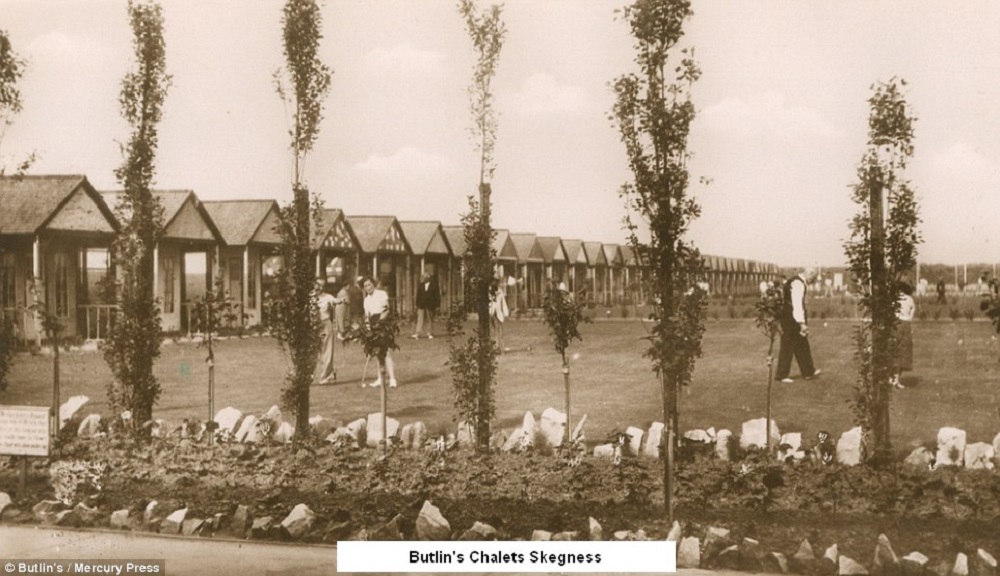

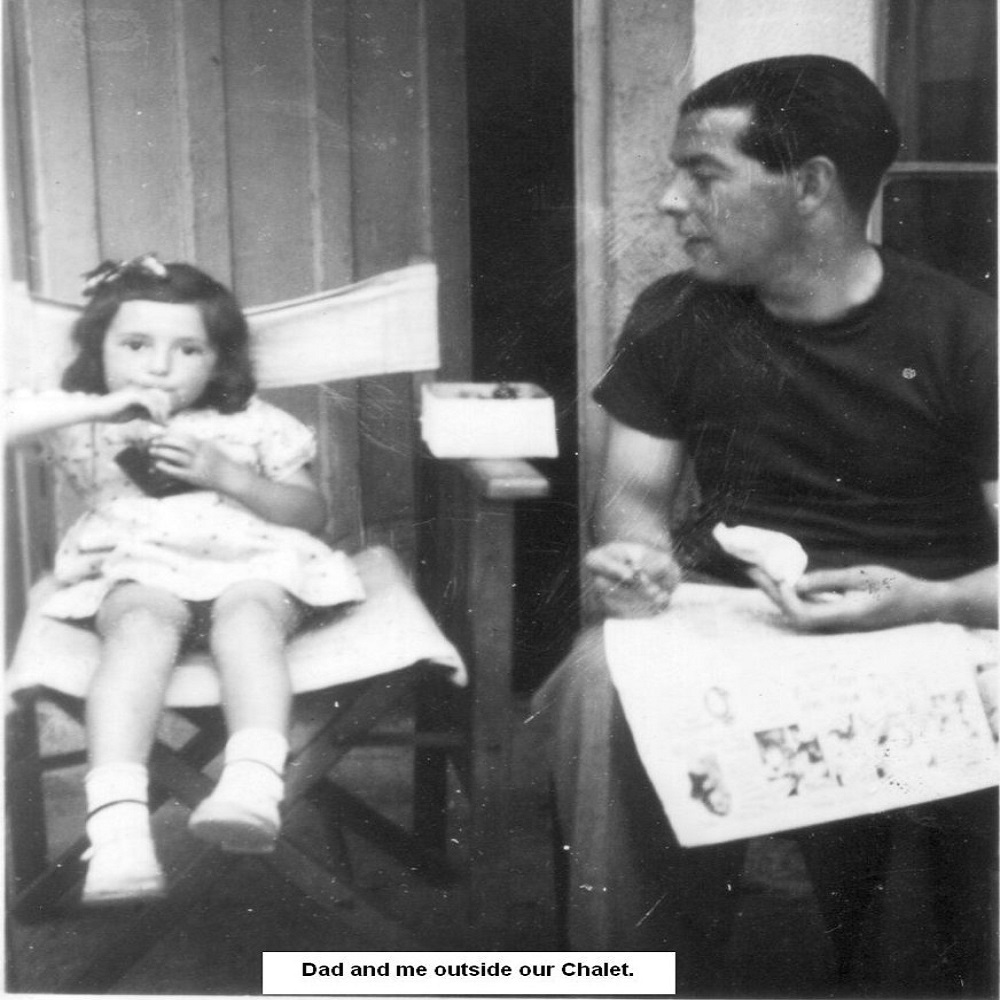

Post-war, it was the likes of George Formby with his ‘little stick of Blackpool rock’, and the Huggett family in ‘Holiday Camp’ (1947 film) that revived appetites for the seaside. The choice for folk like us was: a holiday camp, a boarding house or caravan. Most of my first holidays were spent at Butlin’s. The camps were to Moston as Narnia was to the real world. Compared to the post war drabness at home, the fresh and brightly painted chalets seemed modern and sophisticated. I slept in a bunk bed and ate three course meals served by a smiling, uniformed waitress – never mind that she dispensed the soup from an earthenware jug rather than a tureen.

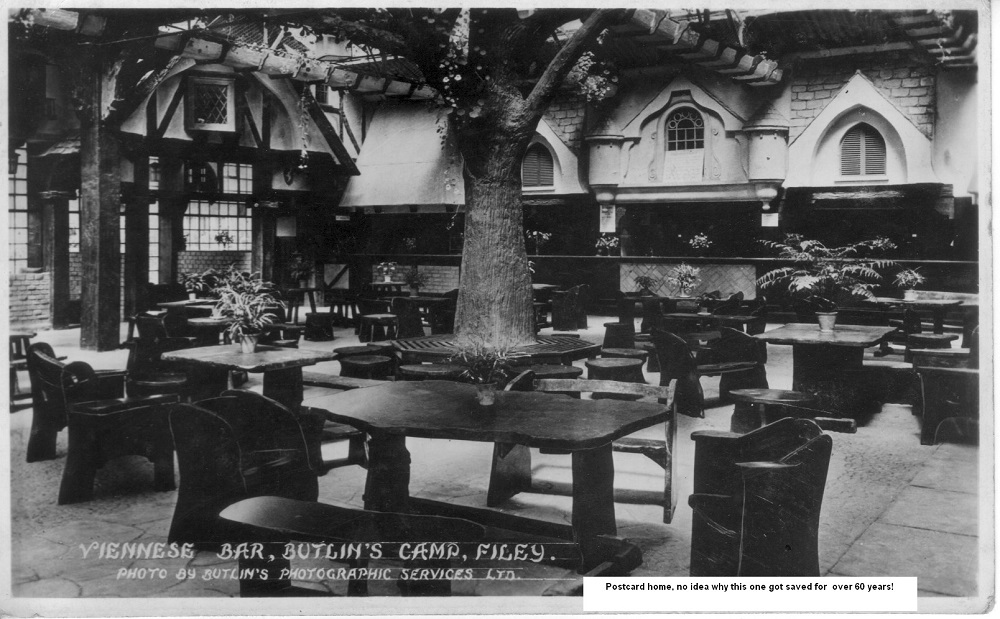

The choice for folk like us was: a holiday camp, a boarding house or caravan. Most of my first holidays were spent at Butlin’s. The camps were to Moston as Narnia was to the real world. Compared to the post war drabness at home, the fresh and brightly painted chalets seemed modern and sophisticated. I slept in a bunk bed and ate three course meals served by a smiling, uniformed waitress – never mind that she dispensed the soup from an earthenware jug rather than a tureen. Without it running away with the spending money, children could swim, play crazy golf or enjoy one of the numerous activities organised to keep them entertained. Also for ‘free’, my parents had the choice of a variety show, or indulging their passion for dancing to an excellent band, in one of the lavish ballrooms.

Without it running away with the spending money, children could swim, play crazy golf or enjoy one of the numerous activities organised to keep them entertained. Also for ‘free’, my parents had the choice of a variety show, or indulging their passion for dancing to an excellent band, in one of the lavish ballrooms.

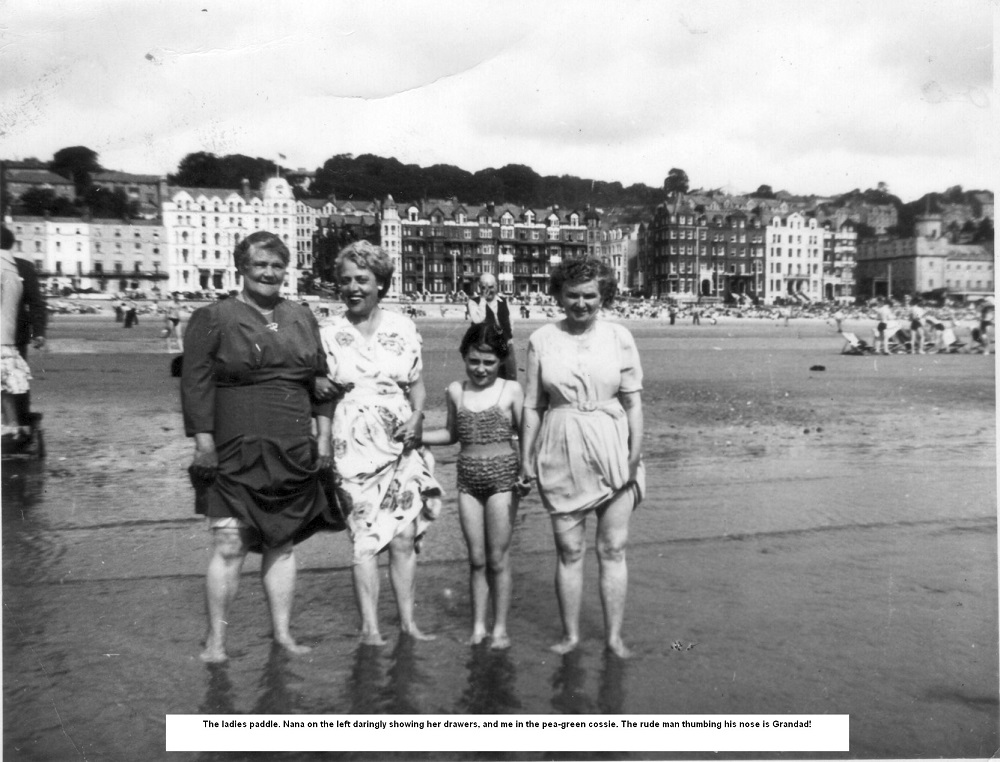

A week before any holiday, our solid dark blue suitcase was dusted off. Its dimensions and wooden banding meant, in a poor light, it could be mistaken for a transatlantic steamer trunk. With two of us sitting on the lid, the case could be persuaded to close on the family’s entire holiday wardrobe. My dad might have been short, but he was strong, and until we got a set of strap-on wheels, he hefted that Leviathan everywhere. Looking like an East End family on the way to pick hops, the rest of us trailed in his wake with our worldly essentials (buckets, spades and comics) poking out of shoulder bags. For men in particular, holidays meant freedom to wear comfortable clothing of their own (or their wife’s) choosing. My granddad’s normal work attire was trilby, suit and tie. His version of holiday chic was what he called ‘a jockey cap and duster jacket’. Dad favoured coloured shirts, shorts and sandals. If it wasn’t actually raining, I seem to recall spending most days in a pea green, elasticated swimming costume, plus canvas shoes that were permanently full of sand.

For men in particular, holidays meant freedom to wear comfortable clothing of their own (or their wife’s) choosing. My granddad’s normal work attire was trilby, suit and tie. His version of holiday chic was what he called ‘a jockey cap and duster jacket’. Dad favoured coloured shirts, shorts and sandals. If it wasn’t actually raining, I seem to recall spending most days in a pea green, elasticated swimming costume, plus canvas shoes that were permanently full of sand.

Travelling to a holiday destination meant a train, coach or (best of all) a ferry. Our most ‘novel’ journey was to Wales during a rail strike. In order that nobody would miss out on their precious week away, every vehicle, no matter its age, was pressed into service. The ancient coach we travelled in was just about adequate on the flat, but when the going got steep, the able bodied had to disembark and walk. In case the bus escaped back downhill if the engine stalled, the men carried large stones to place behind the wheels. Without doubt, my best travel memories were of the Isle of Man ferry. You could sit on deck or lie about in the saloon on a day bed with tasselled, sausage shaped cushions.

Without doubt, my best travel memories were of the Isle of Man ferry. You could sit on deck or lie about in the saloon on a day bed with tasselled, sausage shaped cushions.

Two incidents, the stuff of family legend, occurred on the crossing to the IOM. The first was when a seagull let go its enormous ‘bomb load’ on great grandma Polly’s best black hat. Years later, granddad and I left to check on the lifeboats, prior to going below for an inspection of the engines. After discharging our duties, we returned to find my sister, then aged 4, tucking into an ice cream. It had been bought to stop her screaming, following dad’s attempts to extract her head from one of the port holes without amputating her ears in the process.

From our sea front boarding house in Douglas, we only had to cross the road to get on to the sands. For a couple of pennies, you could travel 1.6 miles on a horse-drawn, ‘toast rack’ tram. We took buses all over the island, but once I mastered reading, the nearby beach shop kept me happily occupied. Some part of each day would find me perusing the extremely saucy and non-PC McGill postcards. For evenings, there was a cinema next door, and a theatre within walking distance. Last year, in the name of security, I was treated to an airport body search. Suddenly it made those uncomplicated childhood holidays look positively idyllic – if you don’t count sunburn, insect bites and sand-filled underwear, that is.

Last year, in the name of security, I was treated to an airport body search. Suddenly it made those uncomplicated childhood holidays look positively idyllic – if you don’t count sunburn, insect bites and sand-filled underwear, that is.

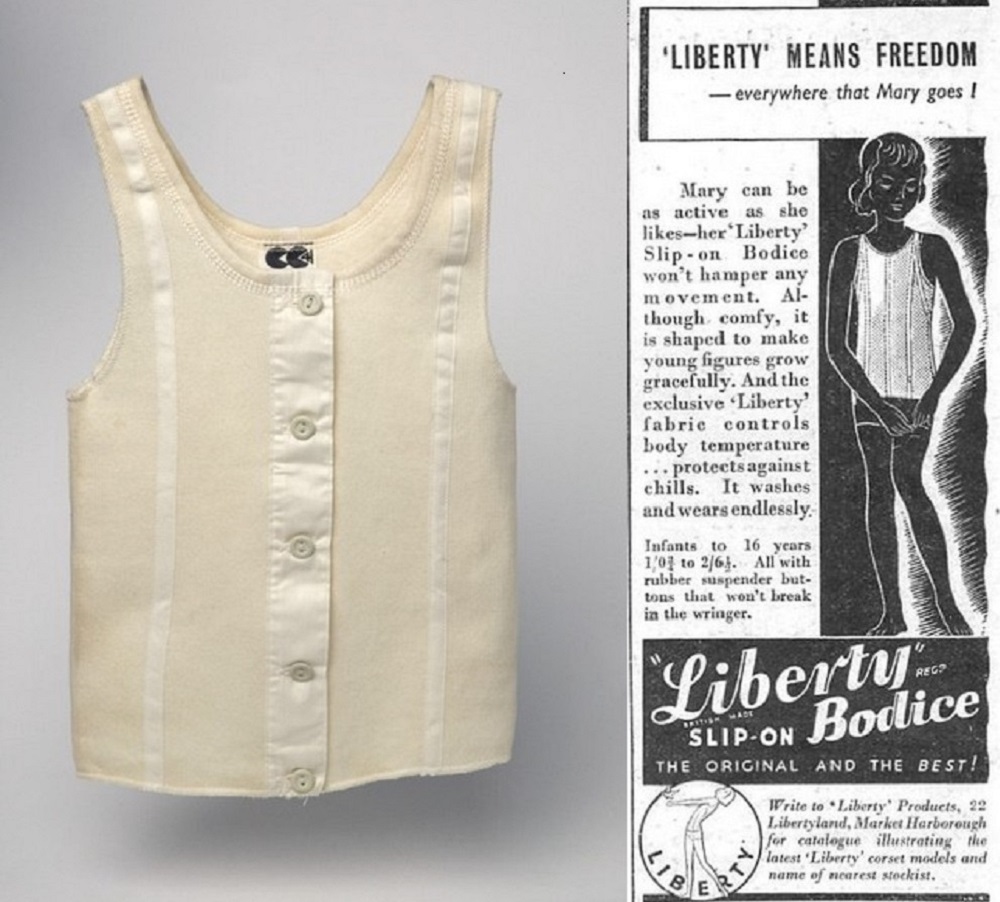

The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory).

The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory). For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts.

For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts. Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent.

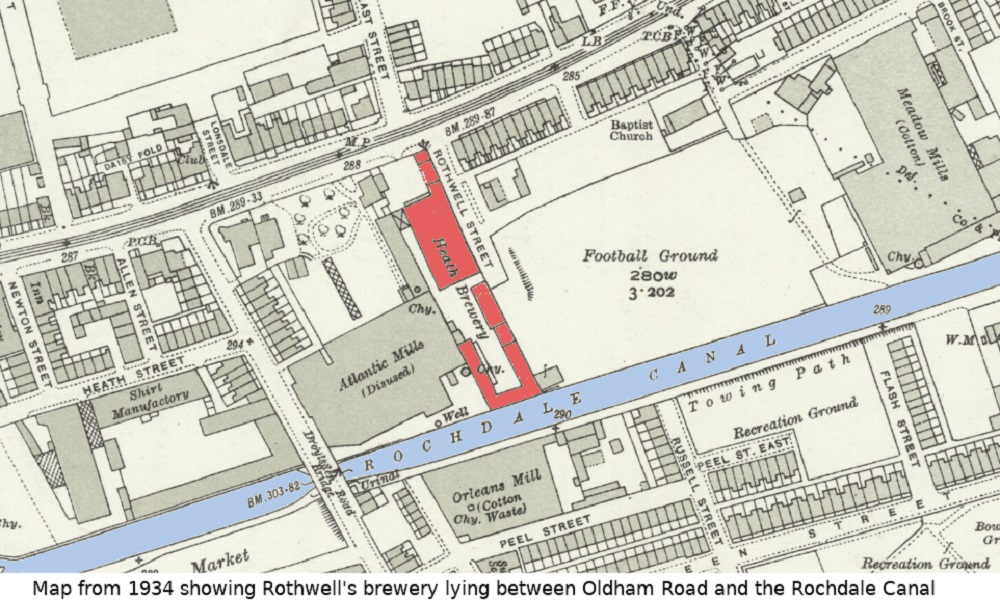

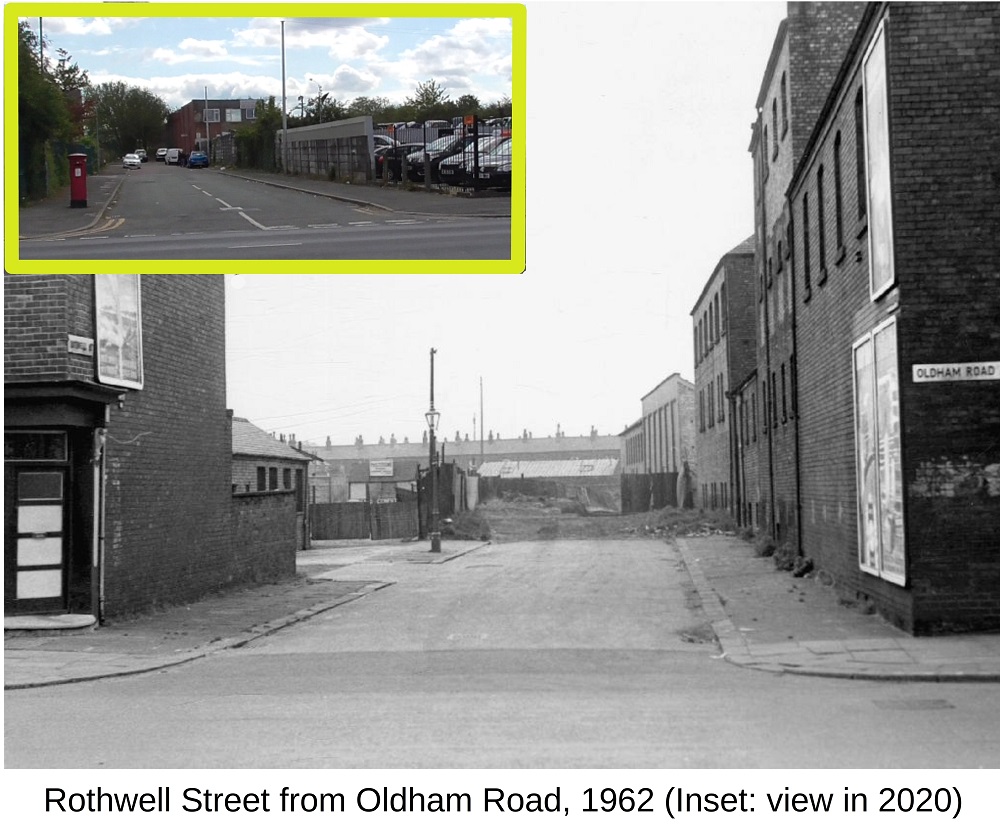

Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent. William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery.

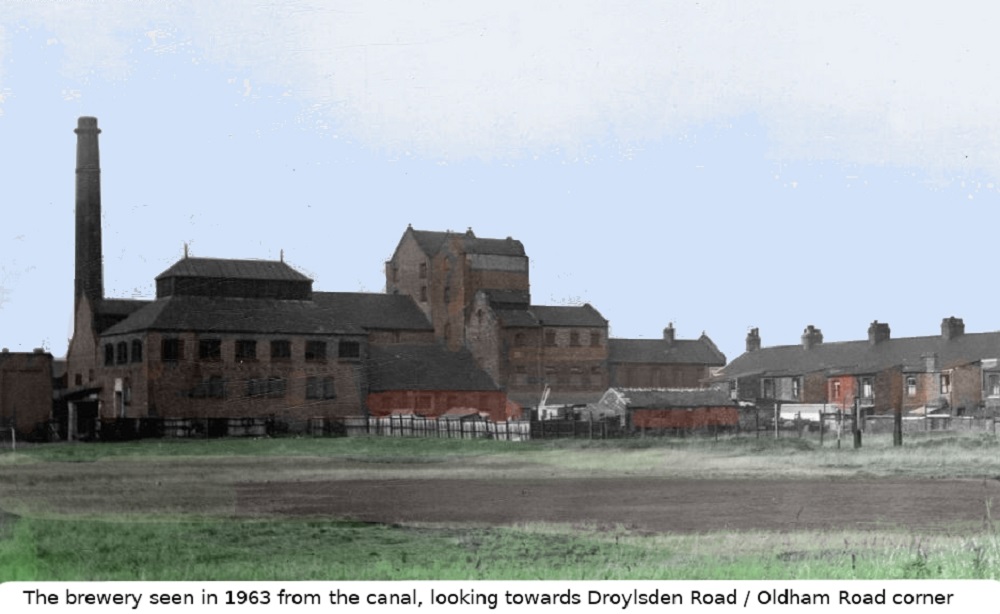

William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery. William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33.

William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33. Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such.

Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such. Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth).

Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth). The Black Horse in 2009

The Black Horse in 2009