1948 saw the launch of the NHS, but the concept of free medicine took a little time to get into the nation’s psyche. In the 1950s, ‘prevention’ continued to be the household watchword. Cod Liver Oil was common, but thankfully the custom of basting children in goose grease before sewing them into their vest for the winter had become obsolete.

Patent medicine manufacturers were relentless in their advertising of nostrums, which at best were little more than a placebo, and at worst contained some highly questionable ingredients. Nevertheless, they remained popular, even when prescription drugs came free. Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma.

Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma.

Children have always caused alarm to parents with the onset of sudden and inexplicable symptoms. In our house, liquid Fever Cure, or Cooling Powders (both made by Fennings) were administered for a high temperature. And until a positive diagnosis was made, spots were painted with Calamine lotion. The cardboard ointment box of Fullers Earth came out for rashes, and drawing ointment (magnesium sulphate) was applied to splinters, boils or infected cuts. The preparation and application of Kaolin poultices was still being taught to St. John’s Ambulance cadets when I joined in 1959.

Back then, even the tiniest corner shop would find wall space for a display of small bottles and packets of patent remedies attached by elastic to a card. Cephos and Beechams powders or Little Liver Pills had their brand names in bold lettering, while the mysterious composition of the products was something a customer had to take on trust. Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets.

Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets.

There were almost as many prudish euphemisms for constipation as there were for the WC. But whatever we called ‘it’, laxatives played a significant part in many people’s lives – especially those who had a dark, frosty yard to cross for a visit to the lav. The switch from brimstone and treacle or turkey rhubarb (Rheum Palmatum) to preparations freely available at corner shops began in the 19th century.

In the fifties, astute manufacturers used advertising to persuade modern mothers they should abandon the old fashioned Syrup of Figs for children’s weekly ‘dosing’. It was replaced by such products as Feen-a-mint which looked and tasted like Beech Nut chewing gum, and Ex-lax that might be passed off as chocolate to the gullible.

Some adults loyally stuck with their old-fashioned Senna pods, Cascara or Epsom salts to ensure ‘regularity’. The more susceptible to brand names transferred to Sedlitz powders, Shure Shield tablets or Beechams Pills – worth a guinea a box, according to the advert…

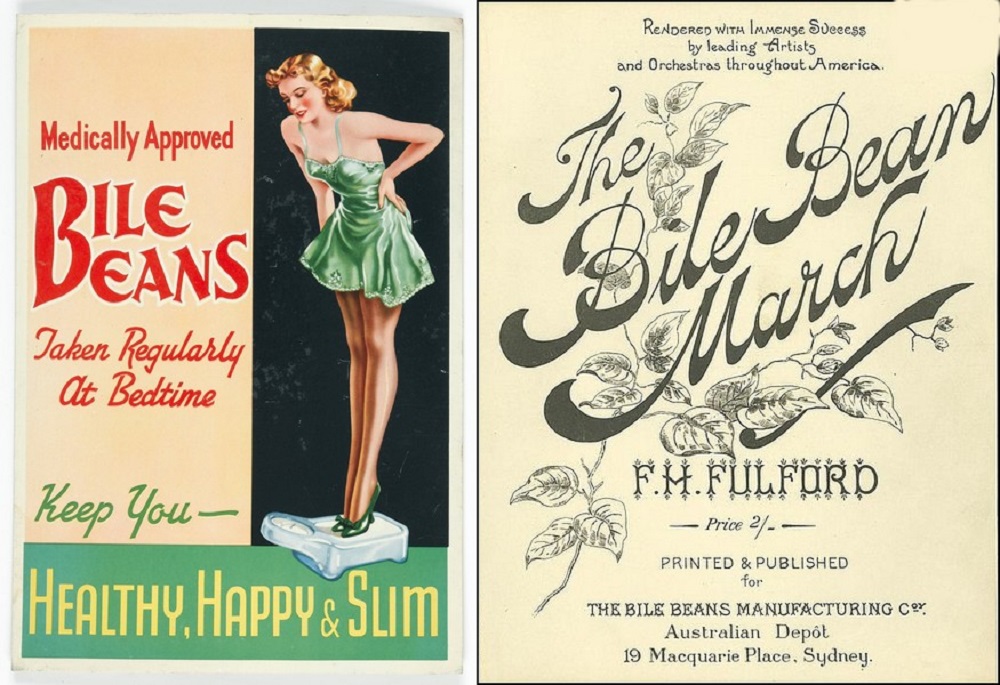

And then there were Bile Beans! Originally marketed as a cure for ‘biliousness’, they contained cascara, rhubarb, liquorice and menthol, rolled in powdered charcoal and coated in gelatine. Soon this apparently universal panacea was also claiming to cure headaches, piles and female weakness. Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans!

Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans!

The manufacturers also produced ‘give-aways’ of cookery and puzzle books, as well as sheet music for the Bile Bean March. In spite of their foul smell and questionable efficacy, Bile Beans continued to be sold until the mid-1980s.

A number of us have managed more than our allotted span of three score years and ten, despite the smearing, dosing and poulticing with medieval sounding concoctions we had to endure. Perhaps there is something to be said for the ‘old magic’ after all.