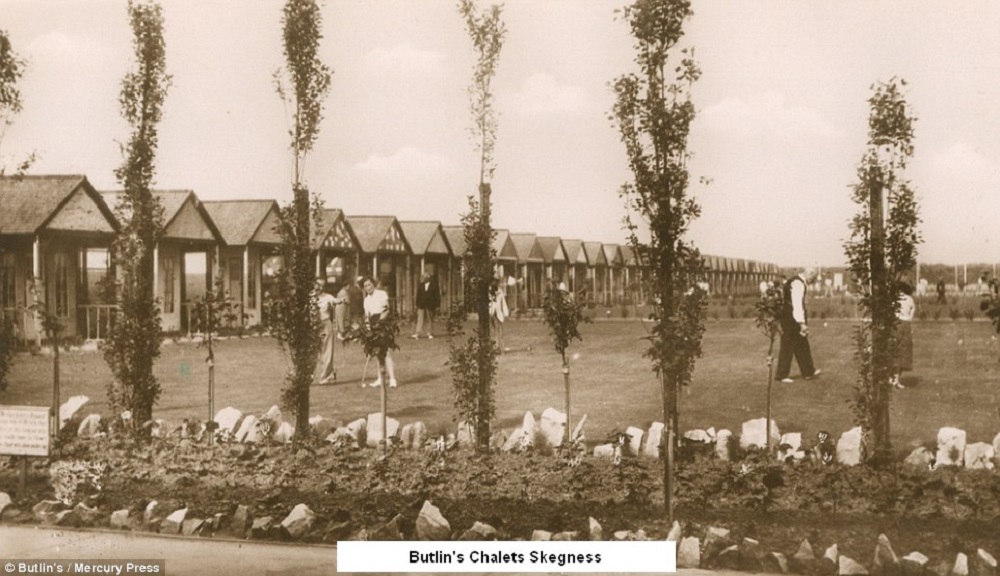

Post-war, it was the likes of George Formby with his ‘little stick of Blackpool rock’, and the Huggett family in ‘Holiday Camp’ (1947 film) that revived appetites for the seaside. The choice for folk like us was: a holiday camp, a boarding house or caravan. Most of my first holidays were spent at Butlin’s. The camps were to Moston as Narnia was to the real world. Compared to the post war drabness at home, the fresh and brightly painted chalets seemed modern and sophisticated. I slept in a bunk bed and ate three course meals served by a smiling, uniformed waitress – never mind that she dispensed the soup from an earthenware jug rather than a tureen.

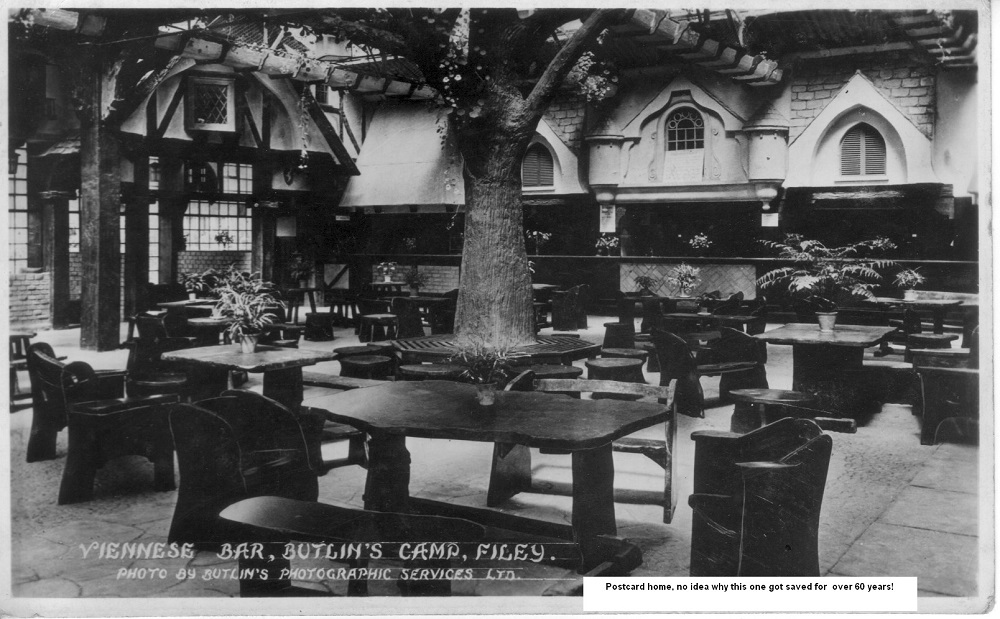

The choice for folk like us was: a holiday camp, a boarding house or caravan. Most of my first holidays were spent at Butlin’s. The camps were to Moston as Narnia was to the real world. Compared to the post war drabness at home, the fresh and brightly painted chalets seemed modern and sophisticated. I slept in a bunk bed and ate three course meals served by a smiling, uniformed waitress – never mind that she dispensed the soup from an earthenware jug rather than a tureen. Without it running away with the spending money, children could swim, play crazy golf or enjoy one of the numerous activities organised to keep them entertained. Also for ‘free’, my parents had the choice of a variety show, or indulging their passion for dancing to an excellent band, in one of the lavish ballrooms.

Without it running away with the spending money, children could swim, play crazy golf or enjoy one of the numerous activities organised to keep them entertained. Also for ‘free’, my parents had the choice of a variety show, or indulging their passion for dancing to an excellent band, in one of the lavish ballrooms.

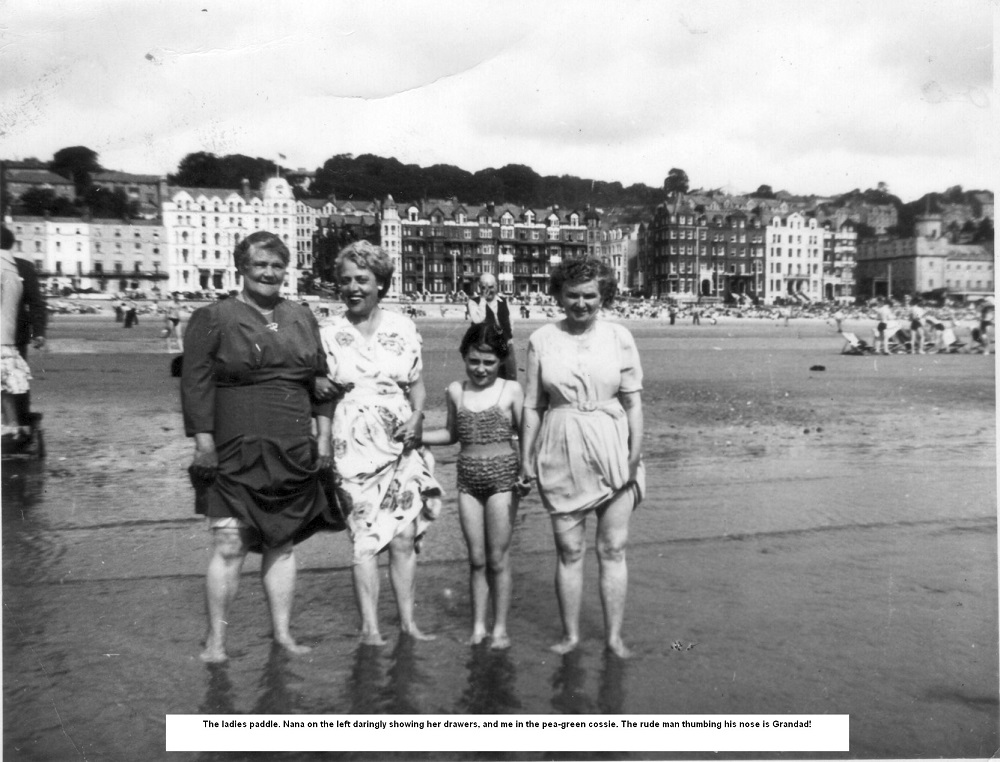

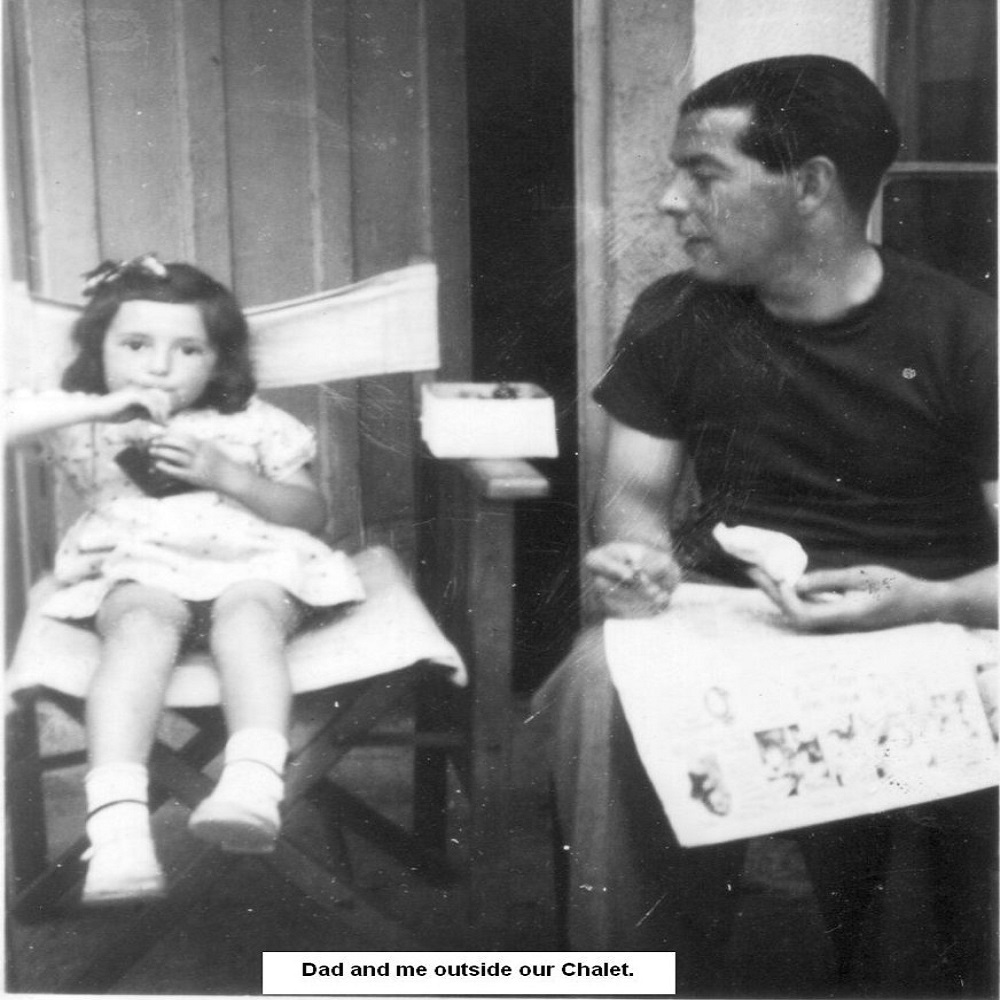

A week before any holiday, our solid dark blue suitcase was dusted off. Its dimensions and wooden banding meant, in a poor light, it could be mistaken for a transatlantic steamer trunk. With two of us sitting on the lid, the case could be persuaded to close on the family’s entire holiday wardrobe. My dad might have been short, but he was strong, and until we got a set of strap-on wheels, he hefted that Leviathan everywhere. Looking like an East End family on the way to pick hops, the rest of us trailed in his wake with our worldly essentials (buckets, spades and comics) poking out of shoulder bags. For men in particular, holidays meant freedom to wear comfortable clothing of their own (or their wife’s) choosing. My granddad’s normal work attire was trilby, suit and tie. His version of holiday chic was what he called ‘a jockey cap and duster jacket’. Dad favoured coloured shirts, shorts and sandals. If it wasn’t actually raining, I seem to recall spending most days in a pea green, elasticated swimming costume, plus canvas shoes that were permanently full of sand.

For men in particular, holidays meant freedom to wear comfortable clothing of their own (or their wife’s) choosing. My granddad’s normal work attire was trilby, suit and tie. His version of holiday chic was what he called ‘a jockey cap and duster jacket’. Dad favoured coloured shirts, shorts and sandals. If it wasn’t actually raining, I seem to recall spending most days in a pea green, elasticated swimming costume, plus canvas shoes that were permanently full of sand.

Travelling to a holiday destination meant a train, coach or (best of all) a ferry. Our most ‘novel’ journey was to Wales during a rail strike. In order that nobody would miss out on their precious week away, every vehicle, no matter its age, was pressed into service. The ancient coach we travelled in was just about adequate on the flat, but when the going got steep, the able bodied had to disembark and walk. In case the bus escaped back downhill if the engine stalled, the men carried large stones to place behind the wheels. Without doubt, my best travel memories were of the Isle of Man ferry. You could sit on deck or lie about in the saloon on a day bed with tasselled, sausage shaped cushions.

Without doubt, my best travel memories were of the Isle of Man ferry. You could sit on deck or lie about in the saloon on a day bed with tasselled, sausage shaped cushions.

Two incidents, the stuff of family legend, occurred on the crossing to the IOM. The first was when a seagull let go its enormous ‘bomb load’ on great grandma Polly’s best black hat. Years later, granddad and I left to check on the lifeboats, prior to going below for an inspection of the engines. After discharging our duties, we returned to find my sister, then aged 4, tucking into an ice cream. It had been bought to stop her screaming, following dad’s attempts to extract her head from one of the port holes without amputating her ears in the process.

From our sea front boarding house in Douglas, we only had to cross the road to get on to the sands. For a couple of pennies, you could travel 1.6 miles on a horse-drawn, ‘toast rack’ tram. We took buses all over the island, but once I mastered reading, the nearby beach shop kept me happily occupied. Some part of each day would find me perusing the extremely saucy and non-PC McGill postcards. For evenings, there was a cinema next door, and a theatre within walking distance. Last year, in the name of security, I was treated to an airport body search. Suddenly it made those uncomplicated childhood holidays look positively idyllic – if you don’t count sunburn, insect bites and sand-filled underwear, that is.

Last year, in the name of security, I was treated to an airport body search. Suddenly it made those uncomplicated childhood holidays look positively idyllic – if you don’t count sunburn, insect bites and sand-filled underwear, that is.

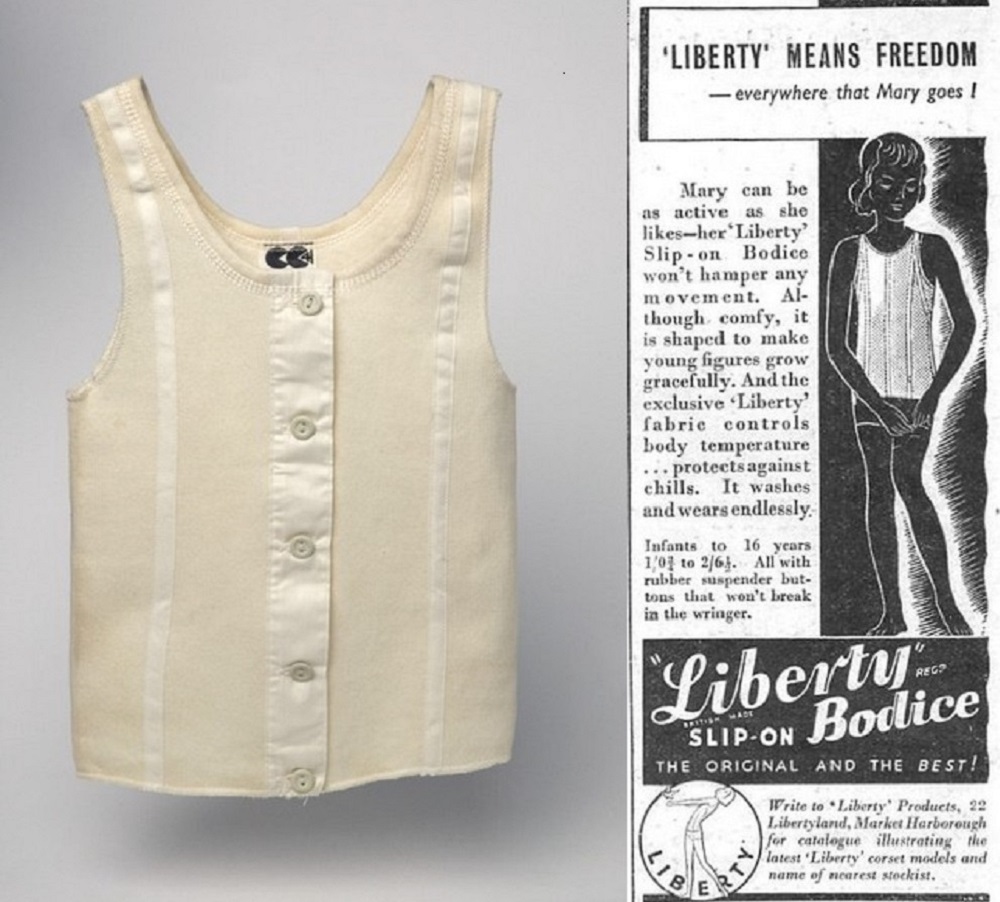

The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory).

The mention of liberty bodices will almost certainly evoke a memory of soft, sticky rubber buttons. The wooden rollers on mangles were notorious for destroying rigid buttons, so rubber was a good substitute (in theory). For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts.

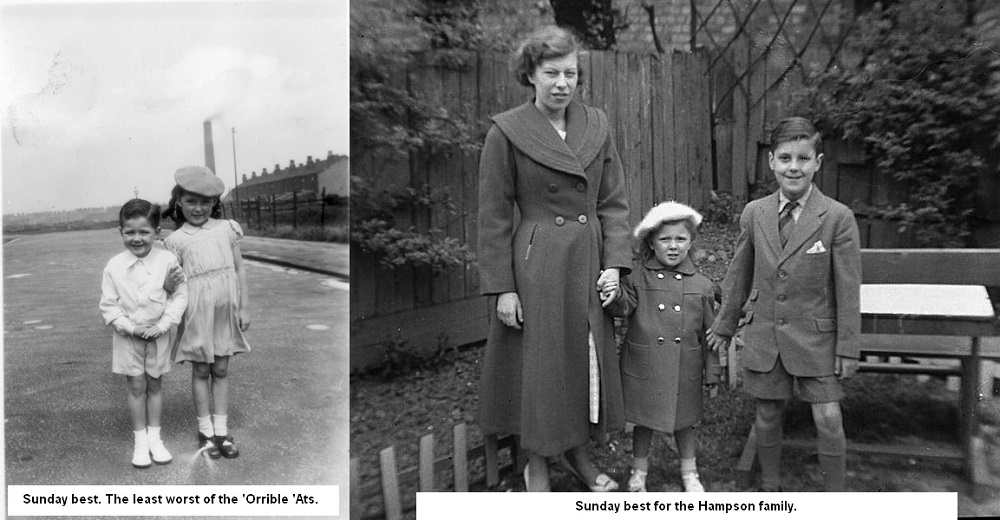

For school, boys usually wore grey or blue shirts and worsted shorts, until they graduated to long trousers in their early teens. I’m reliably informed that in winter, cold, wet legs were rubbed red raw by the coarse fabric of those shorts. Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent.

Adults, and my mother in particular, failed to appreciate that chucking girls’ hats on to tall hedges was a favourite pastime of local boys. The lace or white cotton gloves we wore for best, didn’t stand up well to scrabbling through privets. But it was either that or go home bare headed to face the wrath of my hat-obsessed parent. In 1907 my Nana (aged 13) went from Collyhurst to London Road on foot every day. After 10 hours machining football shirts, she came home, collected a basin and set off to buy ‘a tuppeny mix’ (vegetables and potatoes) for her tea. Despite her mother’s poor example, Nana became an excellent cook.

In 1907 my Nana (aged 13) went from Collyhurst to London Road on foot every day. After 10 hours machining football shirts, she came home, collected a basin and set off to buy ‘a tuppeny mix’ (vegetables and potatoes) for her tea. Despite her mother’s poor example, Nana became an excellent cook. Meat and potato pie, like Nana used to make!

Meat and potato pie, like Nana used to make! When we lived with my grandparents, the larder always contained a large jam tart or fruit pie – fresh fruit in summer (winberry was favourite) and raisins or sultanas in winter. Homemade cakes were coconut, fruit or parkin – all delicious, as was Nana’s treacle toffee.

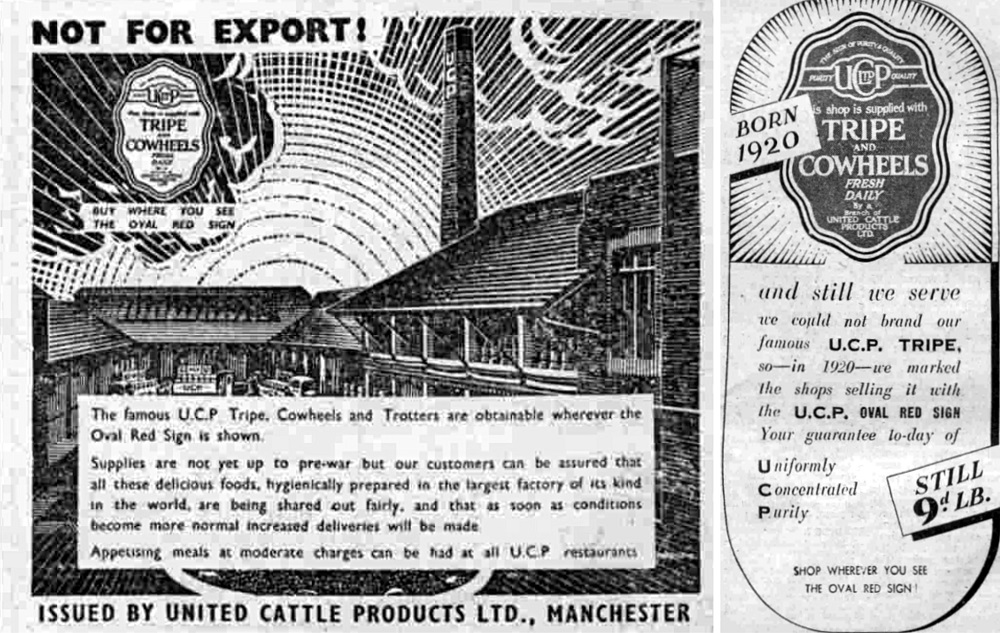

When we lived with my grandparents, the larder always contained a large jam tart or fruit pie – fresh fruit in summer (winberry was favourite) and raisins or sultanas in winter. Homemade cakes were coconut, fruit or parkin – all delicious, as was Nana’s treacle toffee. Many households relied on ‘the chippy’ for a ready to eat meal. However there were one or two things that could almost be called convenience foods. My granddad’s favourites were black pudding with plenty of fat and the kind of dark tripe that looked like a filthy wash leather. The rest of us contented ourselves with pies, crumpets or pikelets.

Many households relied on ‘the chippy’ for a ready to eat meal. However there were one or two things that could almost be called convenience foods. My granddad’s favourites were black pudding with plenty of fat and the kind of dark tripe that looked like a filthy wash leather. The rest of us contented ourselves with pies, crumpets or pikelets. Black tripe – Grandad’s favourite!

Black tripe – Grandad’s favourite! Next time you pop something in the microwave, spare a thought for those fifties housewives. With the most basic facilities, and only a few shillings left from the week’s housekeeping, they managed to produce tasty meals cooked from scratch, day in, day out.

Next time you pop something in the microwave, spare a thought for those fifties housewives. With the most basic facilities, and only a few shillings left from the week’s housekeeping, they managed to produce tasty meals cooked from scratch, day in, day out.