In the 1950s, northern women in their wrapover pinnies, headscarves or hairnets were on their knees at home more often than in church.

Laying fires, black leading grates, and scrubbing floors were only a few of the many domestic rituals performed on hands and knees – but there was a revolution on its way. What we have learned to call ‘white goods’, were slowly insinuating themselves into working class homes, though they were almost never white in those days.

What we have learned to call ‘white goods’, were slowly insinuating themselves into working class homes, though they were almost never white in those days.

It would be some time yet before wash boilers or ‘Dolly tubs’ were entirely replaced by electric washing machines. And, for every meal cooked on one of the new enamel gas stoves, there were plenty still produced in ovens needing a weekly black leading.

‘Stoning’ steps was done for pride, and in areas like ours, it was a measure of a housewife’s respectability. Donkey stones could be had from the rag and bone man in exchange for old clothing. Balloons and windmills on sticks were also on offer – guess what I had to ask for?

I was sometimes allowed to brown stone the back step. Cream stone was reserved for the front which nana always did herself. Getting the bedding and towels for a large family washed and dried, especially in winter, was worth every penny of the small sum charged for a wash-house ‘ticket’. Dilapidated prams had a second incarnation once their life as baby carriages was over, and it was a common sight to see a woman pushing one to the wash-house with the week’s laundry nestling under the hood.

Getting the bedding and towels for a large family washed and dried, especially in winter, was worth every penny of the small sum charged for a wash-house ‘ticket’. Dilapidated prams had a second incarnation once their life as baby carriages was over, and it was a common sight to see a woman pushing one to the wash-house with the week’s laundry nestling under the hood.

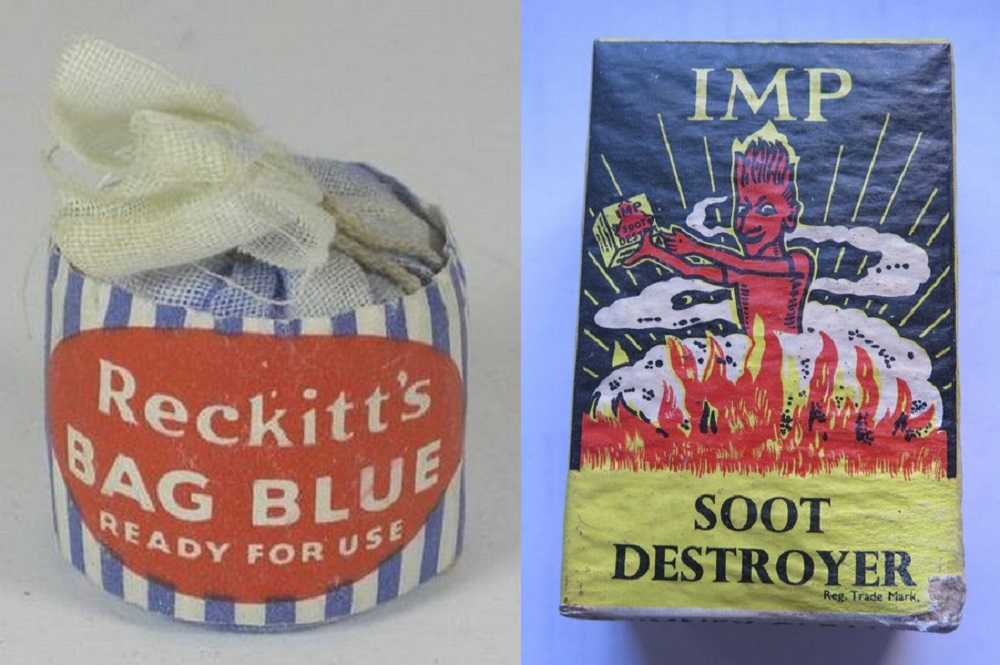

At our house, ‘body linens’ were done at home. I used to enjoy scrubbing my granddad’s loose collars with a nail brush and yellow soap, while his shirts were getting a hot wash in the (gas) boiler. Less robust items went into the dolly tub for a possing. Whites were dolly-blued and sometimes starched, while curtains, dingy from much laundering, got a freshening up in ‘dolly cream’. Vintage ‘washing machine and mangle (photo compliments of Direct Discounts, Oldham, purveyors of present day appliances).

Vintage ‘washing machine and mangle (photo compliments of Direct Discounts, Oldham, purveyors of present day appliances).

Our own nod toward modernity came when the large mangle was replaced by a wringer. It had rubber rollers that folded away under an enamel top that made a useful work surface.

On washing day, a ‘maiden’ (clothes drier) stood open around the oven and above there was a rack, suspended from the ceiling, raised and lowered on a pulley and used for airing. Airing rack still in use today (photo compliments of the editor’s mother-in-law)

Airing rack still in use today (photo compliments of the editor’s mother-in-law)

Due to her mistrust of electricity, nana’s ironing was done with a flat iron on an old blanket spread across the kitchen table.

City planners were rightly proud of the council houses that replaced the 200-year-old slum terraces of Ancoats and Collyhurst. The new houses had hot water, inside toilets and bathrooms, and the mixed blessing of indoor coal storage. Coal ’oles were handily situated next to kitchens and living rooms. Many a housewife’s heart must have broken as she saw the black dust settling on her newly cleaned surfaces with every sack of ‘nutty slack’ the coalman tipped.

Fires, grates and fenders got daily attention, but there was always the fear of incurring a fine for setting the chimney ablaze. There was a patent product called the ‘Imp’ which was put onto the fire to somehow dislodge or disperse the soot from the chimney. The flues on the back-to-back oven also required regular attention. First, kitchen shelves and surfaces were cleared and rugs taken outside. Then a housewife would kneel on the floor with a complicated array of long handled fire irons spread out on newspaper. Ash, fine enough to fly up at the least breath, was raked out first, followed by oily and rather sinister looking soot. Both were consigned to the dustbin before the kitchen was put to rights again.

The flues on the back-to-back oven also required regular attention. First, kitchen shelves and surfaces were cleared and rugs taken outside. Then a housewife would kneel on the floor with a complicated array of long handled fire irons spread out on newspaper. Ash, fine enough to fly up at the least breath, was raked out first, followed by oily and rather sinister looking soot. Both were consigned to the dustbin before the kitchen was put to rights again.

Floors and surfaces were scrubbed and the clean shelves lined with new oil-cloth (sometimes called American cloth) – ours had a scalloped edge cut along the front to make it look nice. Clothes were returned to the rack, pots and pans went back on shelves, and, following a good beating, and mats were put down on the floor again.

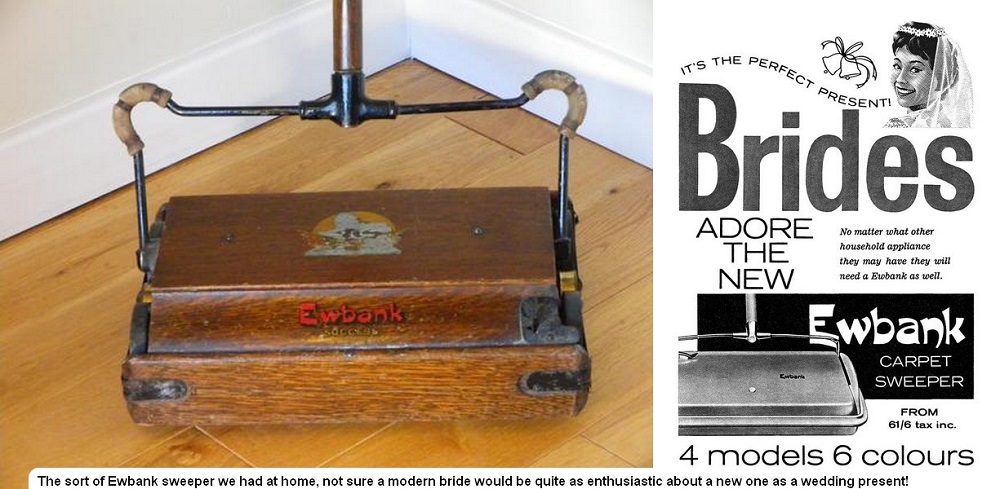

That kneeling band of indomitable women, and the language of their labours, has long since been consigned to history. How many people today have heard of dolly blue, donkey stones, Zebo black lead, Duraglit, Cardinal Red, the humble posser or a Ewbank carpet sweeper?

Acknowledgements: Direct Discounts, Oldham

Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma.

Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma. Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets.

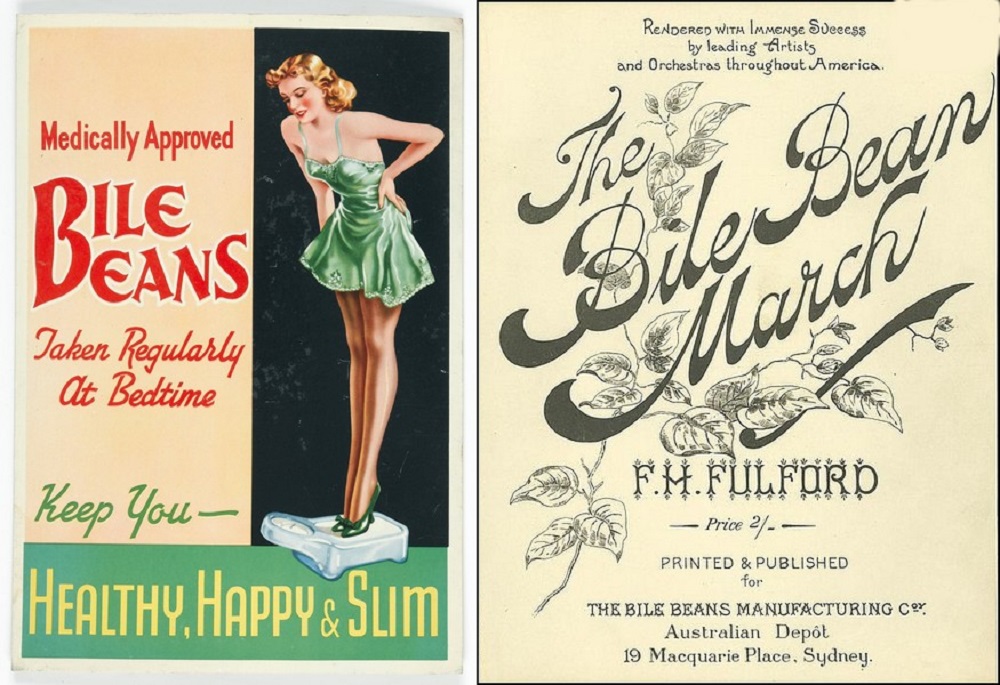

Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets. Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans!

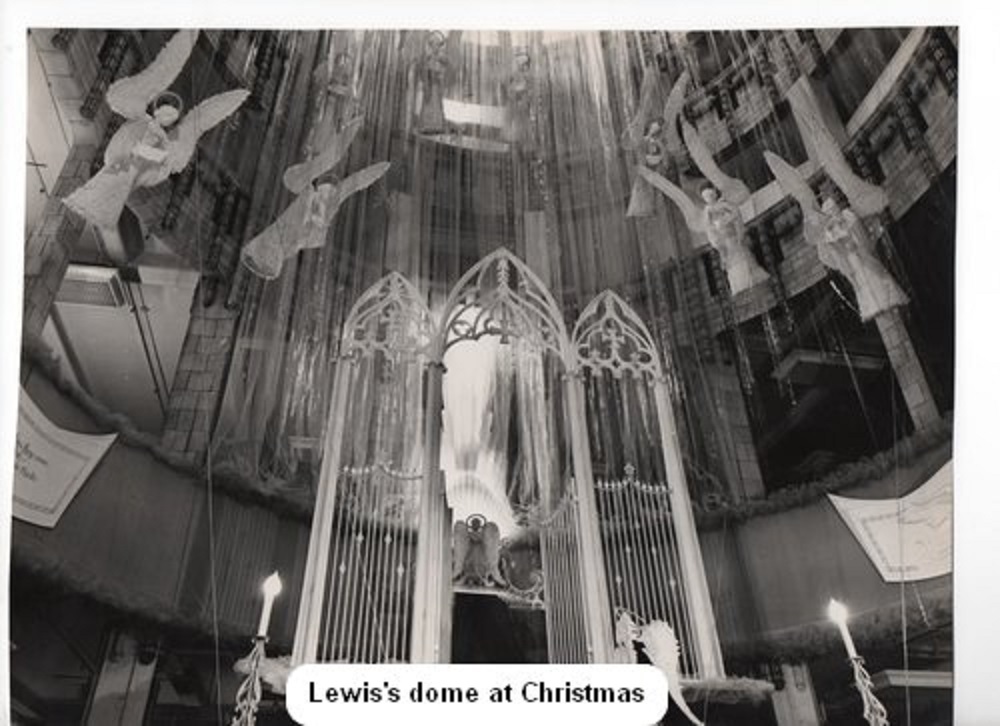

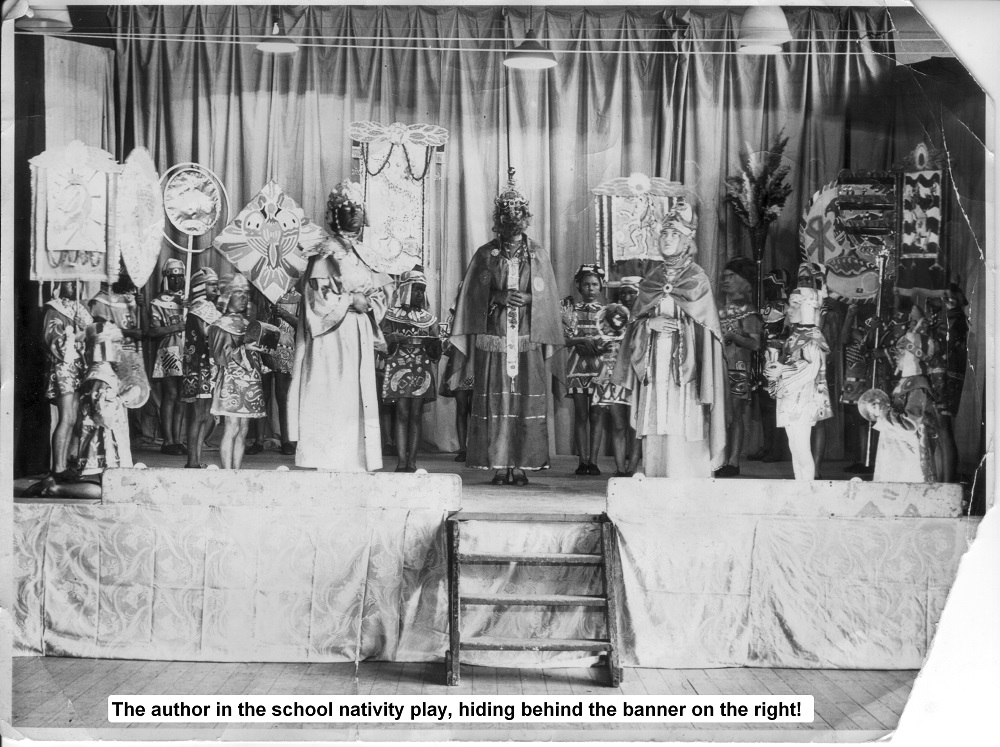

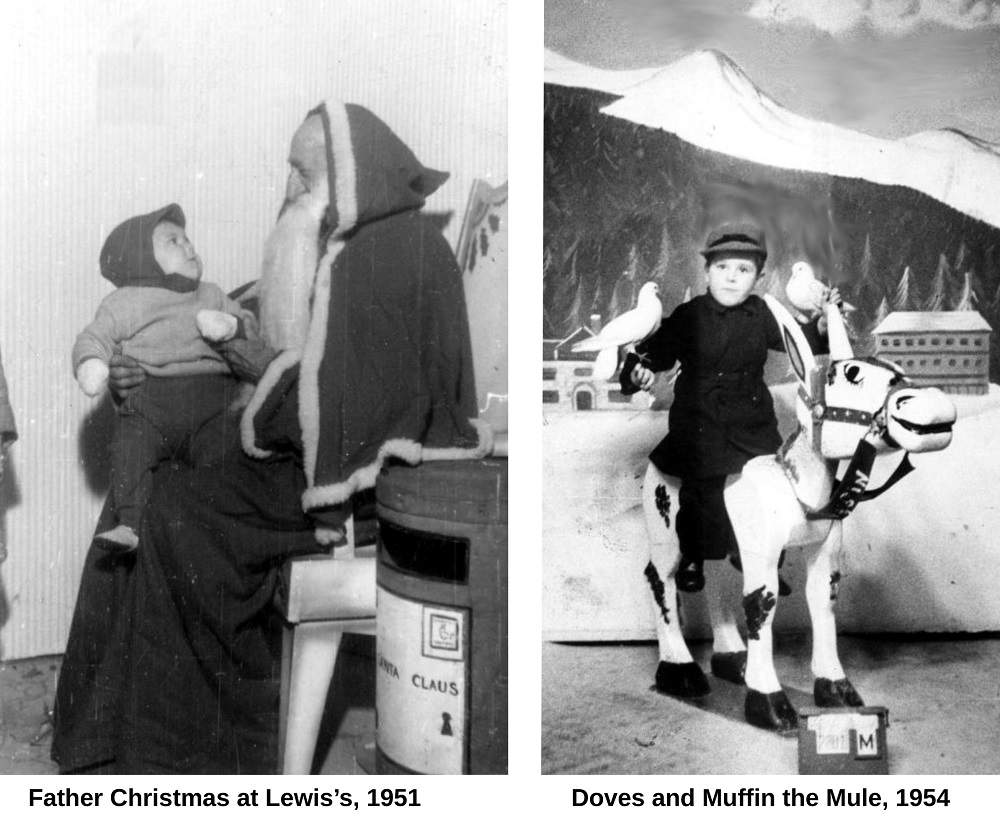

Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans! Queuing for Father Christmas was an annual ritual, but the cardboard and cotton wool grotto was something of a let down after that amazing dome. However, the ‘gift’ of a toy sweet shop, post office, or bus conductor’s set, was some consolation for that interminable wait.

Queuing for Father Christmas was an annual ritual, but the cardboard and cotton wool grotto was something of a let down after that amazing dome. However, the ‘gift’ of a toy sweet shop, post office, or bus conductor’s set, was some consolation for that interminable wait. At home, twisted streamers, paper chains (homemade) and a few balloons constituted our decorations. For the ‘Christmas tree’, picture a piece of dowel stuck into a 6-inch diameter block of wood, painted red. Then imagine stiff, dark green bottle brush ‘branches’ in a shape something like a fir tree. The bare wire ends of the branches were once tipped with artificial berries, but they had long since disappeared. My job was to roll red plasticine into little balls and stick them onto the wire, to avoid anyone’s eye getting poked out.

At home, twisted streamers, paper chains (homemade) and a few balloons constituted our decorations. For the ‘Christmas tree’, picture a piece of dowel stuck into a 6-inch diameter block of wood, painted red. Then imagine stiff, dark green bottle brush ‘branches’ in a shape something like a fir tree. The bare wire ends of the branches were once tipped with artificial berries, but they had long since disappeared. My job was to roll red plasticine into little balls and stick them onto the wire, to avoid anyone’s eye getting poked out. Alcohol wasn’t routinely found in most homes, but at Christmas we pushed the boat out with a bottle of QC port and a sherry. By the end of the decade, Babycham had made an appearance, and one year we even had advocaat (ugh).

Alcohol wasn’t routinely found in most homes, but at Christmas we pushed the boat out with a bottle of QC port and a sherry. By the end of the decade, Babycham had made an appearance, and one year we even had advocaat (ugh).