If the 1605 plotters had made the attempt on the life of James I with a dagger, would it still be commemorated 400 years later?

Round our way, Halloween came a poor second to logging and ‘penny for the guy’. Enterprising lads shone torches into back yards and gardens, looking for discarded furniture and old wood. The occupant of the house would be approached and politely asked if they wanted it removing. Too curt a refusal could result in the ‘liberation’ of said article, along with a section of garden fence.

The brick back yard air-raid shelters had a flat roof that was ideal for keeping wood out of sight of rival loggers. An alarm system consisting of a string of strategically placed tin cans was supposed to alert one of the gang whose bedroom overlooked the back yard – a triumph of hope over experience if ever I heard one. My recall of actual bonfires in Moston is rather sketchy, but fireworks are another matter. Dad chose ours individually and I spent days sorting through the collection stored in the biscuit tin under my bed (what’s Health and Safety?).

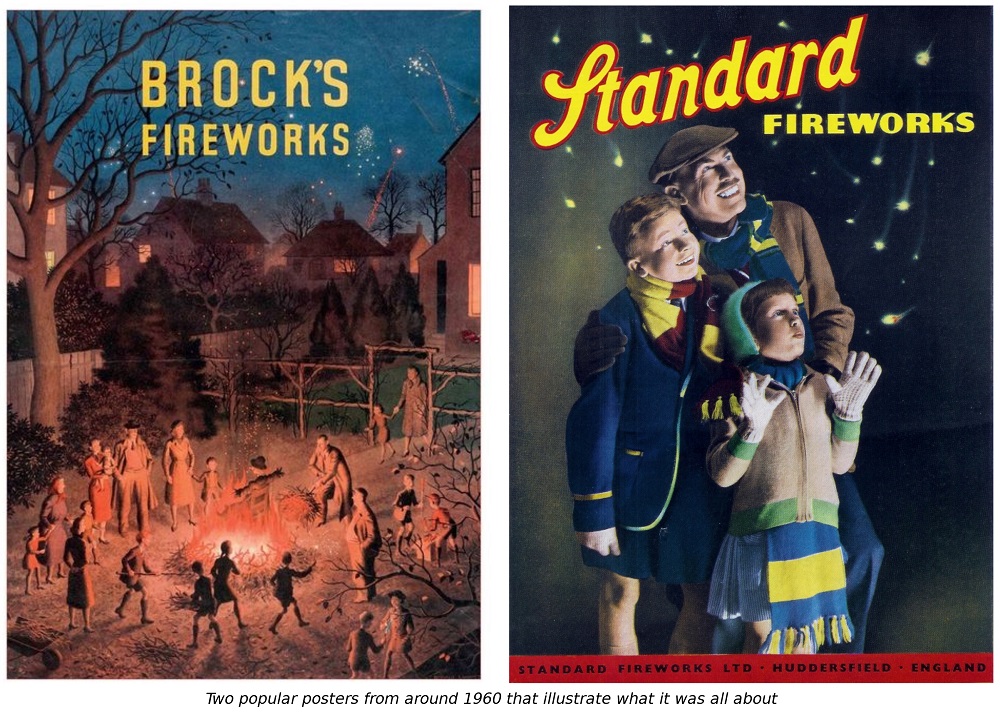

My recall of actual bonfires in Moston is rather sketchy, but fireworks are another matter. Dad chose ours individually and I spent days sorting through the collection stored in the biscuit tin under my bed (what’s Health and Safety?).

Rip-raps were my favourite and, along with Snowstorms, Golden Rain and other tamer fireworks, cost about three halfpence (approximately half a decimal penny). Pin wheels, rockets and sparklers varied in size and were generally more expensive. Roman candles could cost as much as a shilling (5p each).

My specific bonfire memories come after our move to New Moston in 1956. Because of its close proximity to Failsworth and Chadderton, the Manchester ‘penny for the guy’ and Oldham’s ‘cob o’ coaling’ co-existed in New Moston. Collecting with a guy was a static activity while ‘cob ‘o coalers’ went door to door chanting…

“We’ve come a cob ‘o coaling, cob o’ coaling, cob ‘o’ coaling, we’ve come a cob o’ coaling for bonfire night.”

The sleeves and trouser legs of old clothes were tied with string and stuffed with screwed up newspaper. With a mask and hat on a pillow case head, you had your guy. My dad was allocated new uniform trousers once a year, so Guy Fawkes often met his doom wearing a third best pair of GPO issue pants with red piping down the seams. For reasons best known to city planners, our large back garden formed a cul-de-sac completely enclosed by those of all the neighbours. It was so far from the house, mum couldn’t chance hanging out washing if it looked like rain. The only way to reach ‘our back’ was via a long, narrow unmade path, snaking around 5 or 6 other gardens. The result of this anomaly was that from 1957 onwards, we hosted the street’s communal bonfire.

For reasons best known to city planners, our large back garden formed a cul-de-sac completely enclosed by those of all the neighbours. It was so far from the house, mum couldn’t chance hanging out washing if it looked like rain. The only way to reach ‘our back’ was via a long, narrow unmade path, snaking around 5 or 6 other gardens. The result of this anomaly was that from 1957 onwards, we hosted the street’s communal bonfire.

A couple of dads would be deputed to let the pooled fireworks off at a steady rate. Most adults brought themselves a kitchen chair to sit on but one memorable year, someone donated an old leather-cloth three piece suite. We took turns sitting on it until it was the only combustible item left. Then the furniture went onto the fire with Guy Fawkes sitting on top. There was always a plentiful supply of things to eat. If you took your own basin, you could help yourself from the large brown jugs of black peas seasoned with salt and vinegar. And there was no shortage of parkin and treacle toffee, both home-made and shop-bought. The obligatory sooty, half raw potatoes were fished out of the ashes, and an unspoken conspiracy proclaimed them delicious.

There was always a plentiful supply of things to eat. If you took your own basin, you could help yourself from the large brown jugs of black peas seasoned with salt and vinegar. And there was no shortage of parkin and treacle toffee, both home-made and shop-bought. The obligatory sooty, half raw potatoes were fished out of the ashes, and an unspoken conspiracy proclaimed them delicious.

Trousers were not our family’s only contribution to the proceedings. Dad brewed ginger beer from one of those strange plants in vogue at the time. The bubbling demi-john had to be racked off regularly, and the larder soon filled up with various vintages that were universally vile. But judging by bonfire consumption rates, less discerning palates than mine appreciated it.

For some inexplicable reason, the sticks from rockets, spent firework cases and sparkler wires held a strange fascination for the kids who dashed out to collect them on November 6th.

The annual aftermath of bonfire night was a week of damp, evil smelling smog. Naphtha flares that can only have added to the pollution, burned at the junctions of major roads. It was black as night by half past two and children were sent home from school early. Buses crept along at a snail’s pace. And rather than waiting for the designated stop, passengers ‘decked off’ the open, rear platform at the nearest point to home.

It’s many years since I was at a communal street bonfire, but as a gesture toward the tradition, I shall be making black peas and parkin, as usual.

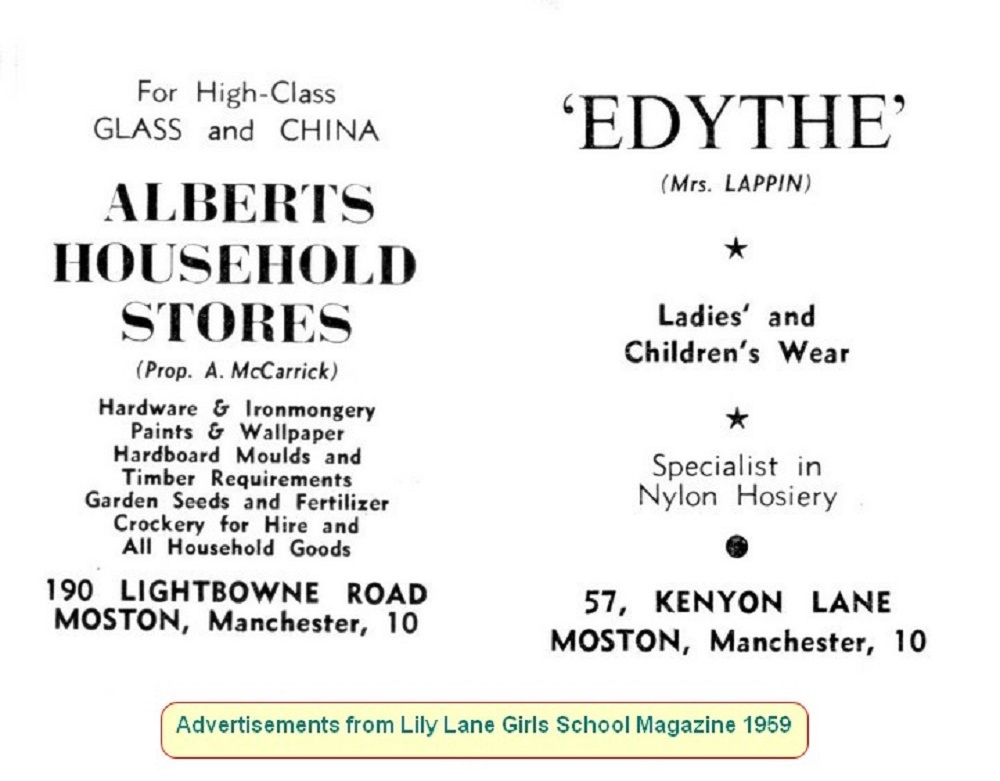

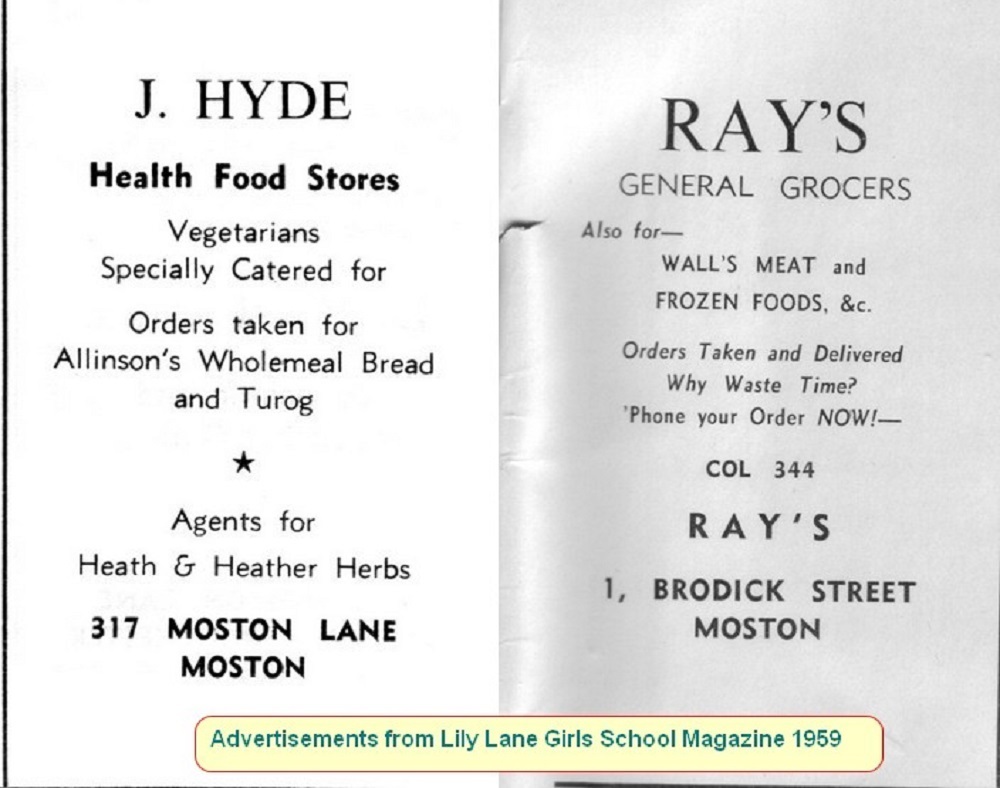

Moston had its specialist shops but almost every street corner had an ‘Open All Hours’ type store, selling everything from Butter Puffs to mothballs and face powder. The one we used had formerly been a terraced house. There was no display window and the door was in the blank gable end wall. On entering, it was bundled firewood stacked under the staircase that first attracted the eye.

Moston had its specialist shops but almost every street corner had an ‘Open All Hours’ type store, selling everything from Butter Puffs to mothballs and face powder. The one we used had formerly been a terraced house. There was no display window and the door was in the blank gable end wall. On entering, it was bundled firewood stacked under the staircase that first attracted the eye. On Ashley Lane there was a chemist, baker, newsagent, butcher, and green-grocer who also sold wet fish. Vegetables came loose and unwashed, necessitating a dedicated ‘potato bag’. Ours was made of rexine, an artificial leather-cloth produced by a company in Hyde. As a boy, my father once forgot the all-important bag, and was told to hold out his gansey (sweater). He did so, and 5 lbs of King Edwards were unceremoniously tipped into it.

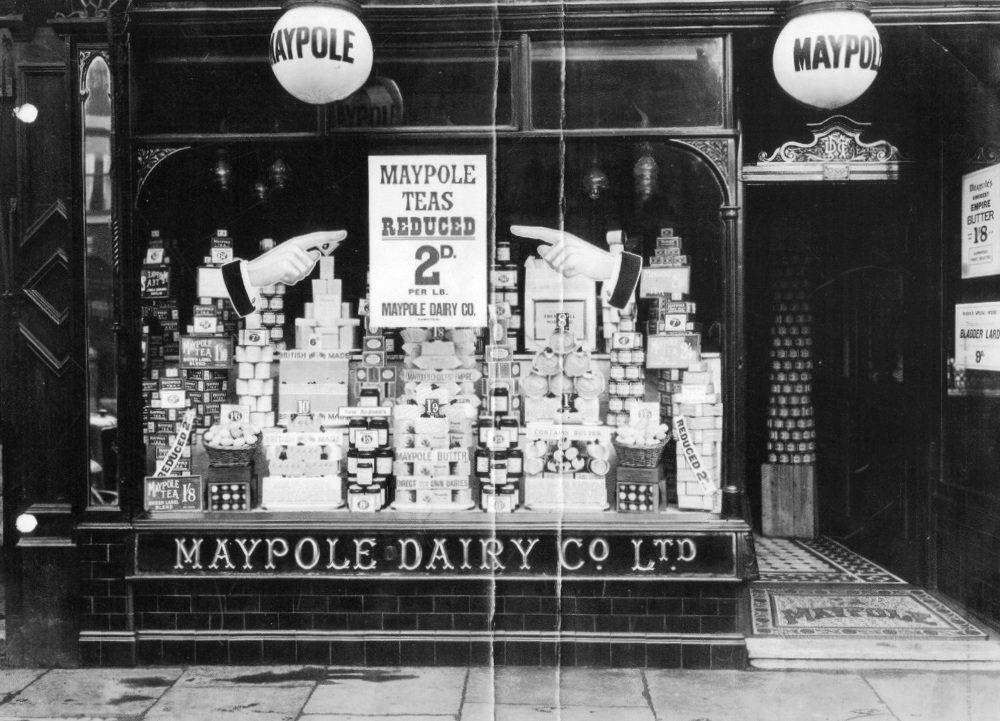

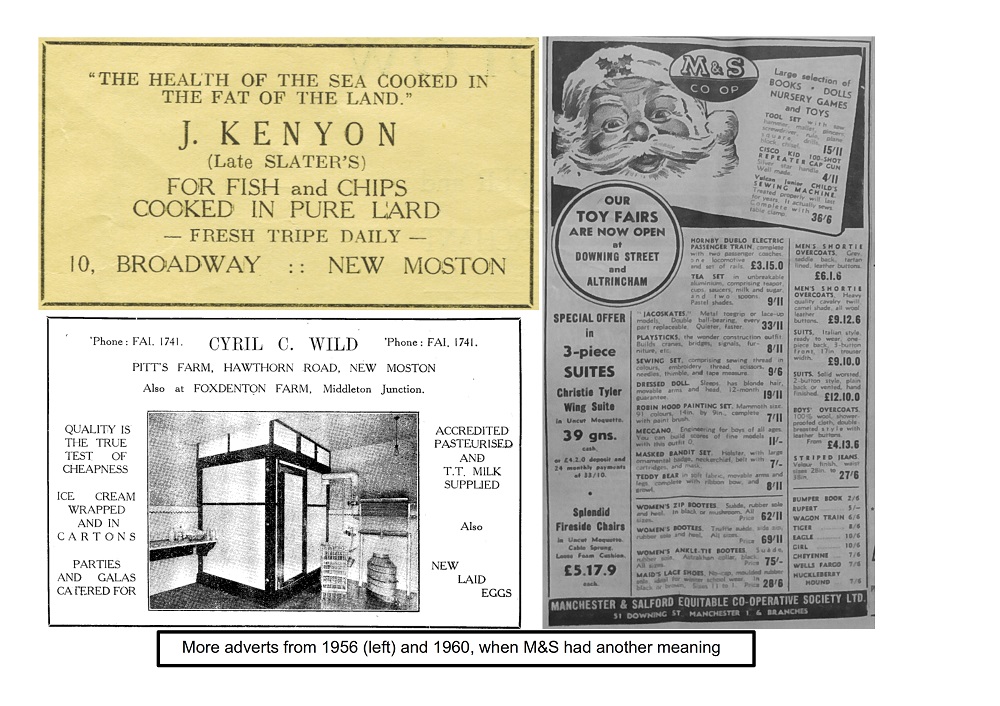

On Ashley Lane there was a chemist, baker, newsagent, butcher, and green-grocer who also sold wet fish. Vegetables came loose and unwashed, necessitating a dedicated ‘potato bag’. Ours was made of rexine, an artificial leather-cloth produced by a company in Hyde. As a boy, my father once forgot the all-important bag, and was told to hold out his gansey (sweater). He did so, and 5 lbs of King Edwards were unceremoniously tipped into it. Saturday was the day for ‘the lane’. The shops on Moston Lane were there to supply all our needs from cradle to grave. There was the Maypole grocers, shoe shops, drapers, dry cleaners, and yes, even an undertaker.

Saturday was the day for ‘the lane’. The shops on Moston Lane were there to supply all our needs from cradle to grave. There was the Maypole grocers, shoe shops, drapers, dry cleaners, and yes, even an undertaker. To my mind, supermarkets will never replace the convenience of nipping round the corner for a bottle of Camp coffee, OK Sauce or a roll of Izal, which when not performing its primary purpose, made excellent tracing paper or a comb kazoo.

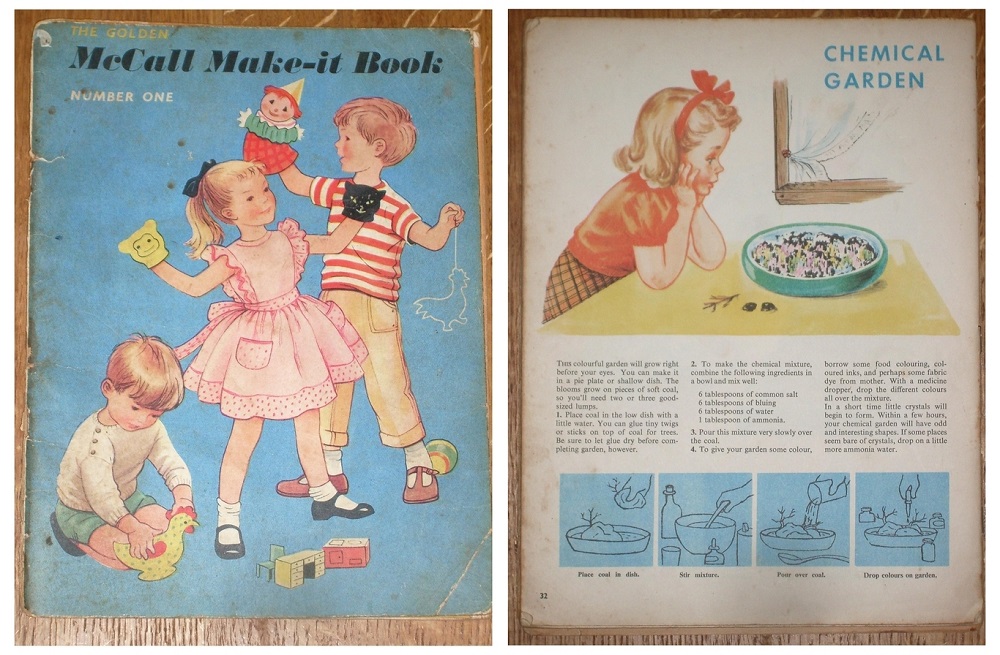

To my mind, supermarkets will never replace the convenience of nipping round the corner for a bottle of Camp coffee, OK Sauce or a roll of Izal, which when not performing its primary purpose, made excellent tracing paper or a comb kazoo. Buildings were created by sliding the modular brick tiles, windows and doors between metal rods inserted into a base. The only down side was that our creations had to be dismantled when the table was needed for meals.

Buildings were created by sliding the modular brick tiles, windows and doors between metal rods inserted into a base. The only down side was that our creations had to be dismantled when the table was needed for meals. Kids used to being feral soon tired of sedentary pastimes and brought scaled-down versions of outdoor games inside. In true wartime ‘make do and mend’ style we used our family’s laundry basket, a wooden crate with sturdy rope handles which normally lived under the kitchen table. On rainy days it could be transformed into a pirate ship or stagecoach under attack from ‘red Indians’, or anything else our imagination conjured up.

Kids used to being feral soon tired of sedentary pastimes and brought scaled-down versions of outdoor games inside. In true wartime ‘make do and mend’ style we used our family’s laundry basket, a wooden crate with sturdy rope handles which normally lived under the kitchen table. On rainy days it could be transformed into a pirate ship or stagecoach under attack from ‘red Indians’, or anything else our imagination conjured up. Time and patience was required for the fiddly cutting out in those pre-sellotape days, when a slip of the scissors could spell disaster. The figures came printed on thin card and the paper outfits had small tabs which folded around the doll to keep them in place. My sister and I often combined forces to act out plays with our dolls as the characters.

Time and patience was required for the fiddly cutting out in those pre-sellotape days, when a slip of the scissors could spell disaster. The figures came printed on thin card and the paper outfits had small tabs which folded around the doll to keep them in place. My sister and I often combined forces to act out plays with our dolls as the characters.