When the industrial revolution began, men, women and children flooded into Manchester seeking work. They found themselves in one up/one down dwellings or multi tenanted houses where the only cooking facility was a pot set on an open fire.

For centuries it was vegetables, barley, suet pastry, pulses and, above all, bread that filled hungry bellies. Punitive Corn Laws that made wheat bread too expensive for workers forced them to subsist on oatcake or Waterloo porridge (oatmeal, water and salt, with perhaps a bit of cheese, red herring or bacon on a Sunday.

Although potatoes came to Britain in the late 16th century, it was some time before the poor came to rely on them as a staple food. By the time workers’ houses had cooking ranges, potatoes and cheaper cuts of meat were the basis of good plain meals still being eaten in the 1950s. But there were exceptions to every rule. In 1907 my Nana (aged 13) went from Collyhurst to London Road on foot every day. After 10 hours machining football shirts, she came home, collected a basin and set off to buy ‘a tuppeny mix’ (vegetables and potatoes) for her tea. Despite her mother’s poor example, Nana became an excellent cook.

In 1907 my Nana (aged 13) went from Collyhurst to London Road on foot every day. After 10 hours machining football shirts, she came home, collected a basin and set off to buy ‘a tuppeny mix’ (vegetables and potatoes) for her tea. Despite her mother’s poor example, Nana became an excellent cook. Meat and potato pie, like Nana used to make!

Meat and potato pie, like Nana used to make!

Once rationing finished, pre-war favourites like meat and potato pie, soup with bacon ribs or ham shank, neck chops, breast of lamb, fried plaice and pot roasted brisket made a return. At home we had something called ‘fat cake’ which nobody else seems to have heard of. It was a sort of plain scone mixture bound together with melted butter and baked in the oven on greaseproof paper. When we lived with my grandparents, the larder always contained a large jam tart or fruit pie – fresh fruit in summer (winberry was favourite) and raisins or sultanas in winter. Homemade cakes were coconut, fruit or parkin – all delicious, as was Nana’s treacle toffee.

When we lived with my grandparents, the larder always contained a large jam tart or fruit pie – fresh fruit in summer (winberry was favourite) and raisins or sultanas in winter. Homemade cakes were coconut, fruit or parkin – all delicious, as was Nana’s treacle toffee.

Apart from milk puddings and custard tart, such desserts as we had came out of a tin. Peaches, pineapple chunks or fruit salad was served with evaporated milk or tinned cream (not to be confused with condensed milk). As far as I recall, I never tasted fresh cream until the late 50s, and it was a revelation after the horrible tinned stuff.

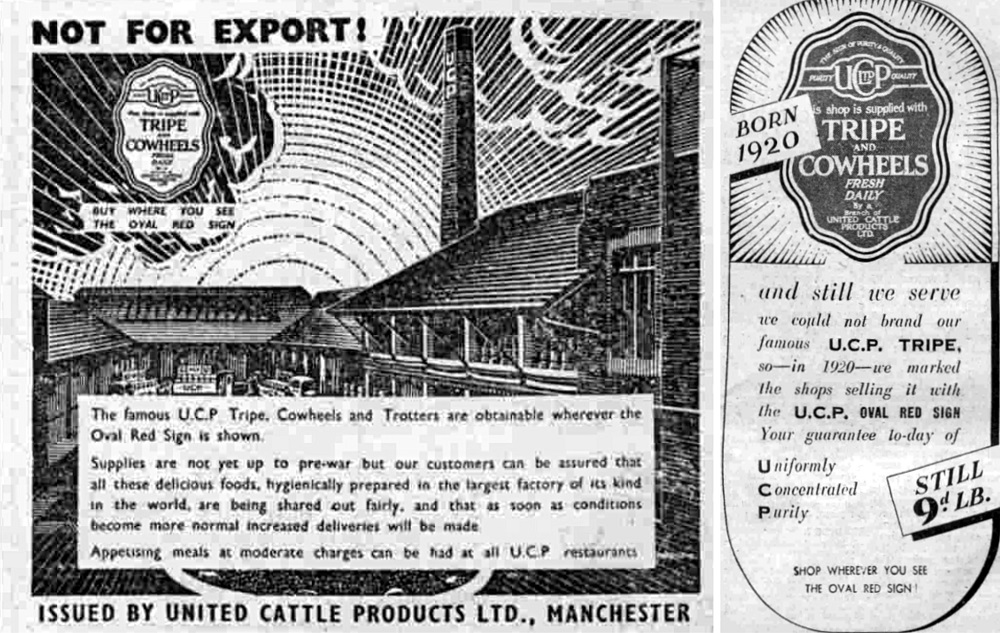

I speak from bitter experience when I say that rose coloured spectacles couldn’t make me nostalgic for the tinned Spam or waterlogged vegetables we ate when mum took on the cooking, when we moved to New Moston. She was the sort of cook who put the Christmas sprouts on to simmer in November. Many households relied on ‘the chippy’ for a ready to eat meal. However there were one or two things that could almost be called convenience foods. My granddad’s favourites were black pudding with plenty of fat and the kind of dark tripe that looked like a filthy wash leather. The rest of us contented ourselves with pies, crumpets or pikelets.

Many households relied on ‘the chippy’ for a ready to eat meal. However there were one or two things that could almost be called convenience foods. My granddad’s favourites were black pudding with plenty of fat and the kind of dark tripe that looked like a filthy wash leather. The rest of us contented ourselves with pies, crumpets or pikelets. Black tripe – Grandad’s favourite!

Black tripe – Grandad’s favourite!

Nowadays it’s almost impossible to imagine how limited the food horizons used to be, especially for the non-meat eaters. Our school cookery lessons only included one vegetarian dish, and that was nut cutlet. Thanks to ingredients unknown 60 years ago, having a vegan or ‘free from’ friend round for tea isn’t the challenge it used to be.

But what I would like to know is why trendy ‘foodies’ have been allowed to claim they invented ‘slow food’? Their gentrification of our traditional dishes has made bacon ribs, oxtail, belly pork and breast of lamb more expensive per pound than a roasting joint.

And while you may find good old sausage and mash on the menu in a gastro pub, it’s more likely to come with a ‘jus’ than simple brown gravy. It seems beer is now obligatory in fish batter and, for all I know, there might be Ovaltine in the soup to give it ‘hipster’ appeal. What’s more, don’t be surprised if your meal arrives on a hub cap with the side order of chips in a plant pot! Next time you pop something in the microwave, spare a thought for those fifties housewives. With the most basic facilities, and only a few shillings left from the week’s housekeeping, they managed to produce tasty meals cooked from scratch, day in, day out.

Next time you pop something in the microwave, spare a thought for those fifties housewives. With the most basic facilities, and only a few shillings left from the week’s housekeeping, they managed to produce tasty meals cooked from scratch, day in, day out.

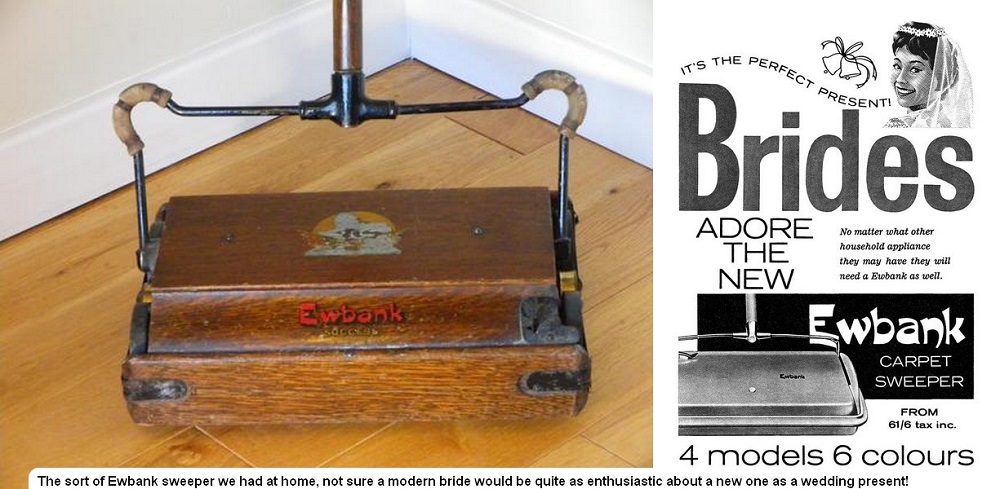

What we have learned to call ‘white goods’, were slowly insinuating themselves into working class homes, though they were almost never white in those days.

What we have learned to call ‘white goods’, were slowly insinuating themselves into working class homes, though they were almost never white in those days. Getting the bedding and towels for a large family washed and dried, especially in winter, was worth every penny of the small sum charged for a wash-house ‘ticket’. Dilapidated prams had a second incarnation once their life as baby carriages was over, and it was a common sight to see a woman pushing one to the wash-house with the week’s laundry nestling under the hood.

Getting the bedding and towels for a large family washed and dried, especially in winter, was worth every penny of the small sum charged for a wash-house ‘ticket’. Dilapidated prams had a second incarnation once their life as baby carriages was over, and it was a common sight to see a woman pushing one to the wash-house with the week’s laundry nestling under the hood. Vintage ‘washing machine and mangle (photo compliments of Direct Discounts, Oldham, purveyors of present day appliances).

Vintage ‘washing machine and mangle (photo compliments of Direct Discounts, Oldham, purveyors of present day appliances).  Airing rack still in use today (photo compliments of the editor’s mother-in-law)

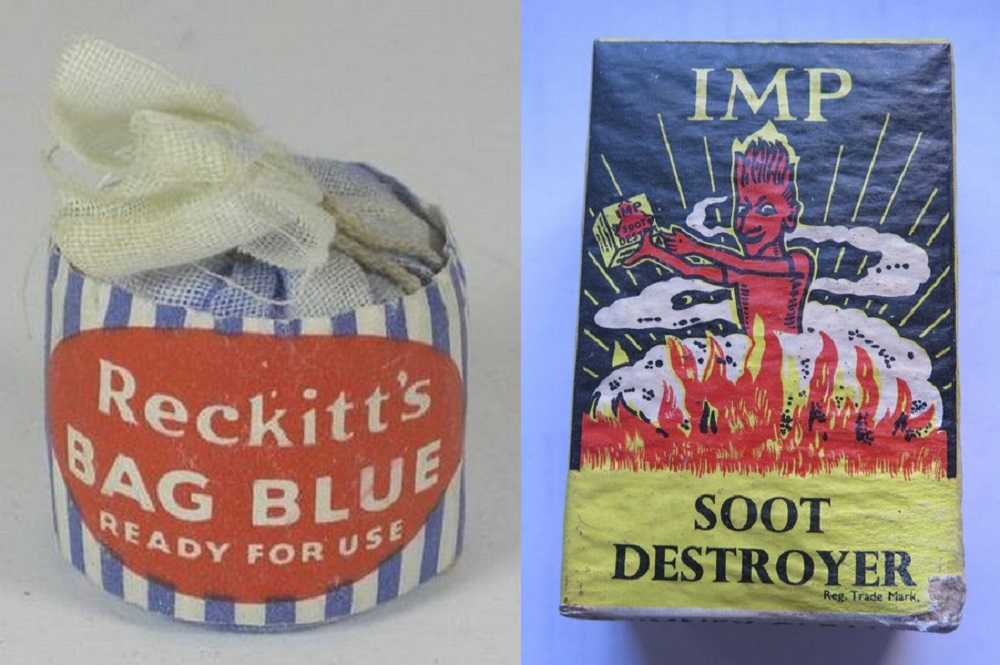

Airing rack still in use today (photo compliments of the editor’s mother-in-law) The flues on the back-to-back oven also required regular attention. First, kitchen shelves and surfaces were cleared and rugs taken outside. Then a housewife would kneel on the floor with a complicated array of long handled fire irons spread out on newspaper. Ash, fine enough to fly up at the least breath, was raked out first, followed by oily and rather sinister looking soot. Both were consigned to the dustbin before the kitchen was put to rights again.

The flues on the back-to-back oven also required regular attention. First, kitchen shelves and surfaces were cleared and rugs taken outside. Then a housewife would kneel on the floor with a complicated array of long handled fire irons spread out on newspaper. Ash, fine enough to fly up at the least breath, was raked out first, followed by oily and rather sinister looking soot. Both were consigned to the dustbin before the kitchen was put to rights again. Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma.

Grandad was asthmatic, so we knew all about ‘bad chests’ in our house. He accepted his NHS inhaler gratefully, but he continued to wear Thermogene next to the skin for luck. Pink in colour, Thermogene’s texture most resembled modern roof insulation, with a smell that was redolent of a chemical weapons establishment. But for those who were put off by its pong, there were always Do-do tablets. Also known as Chesteze, they contained caffeine and ephedrine to relieve breathlessness, wheezing and other symptoms of asthma. Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets.

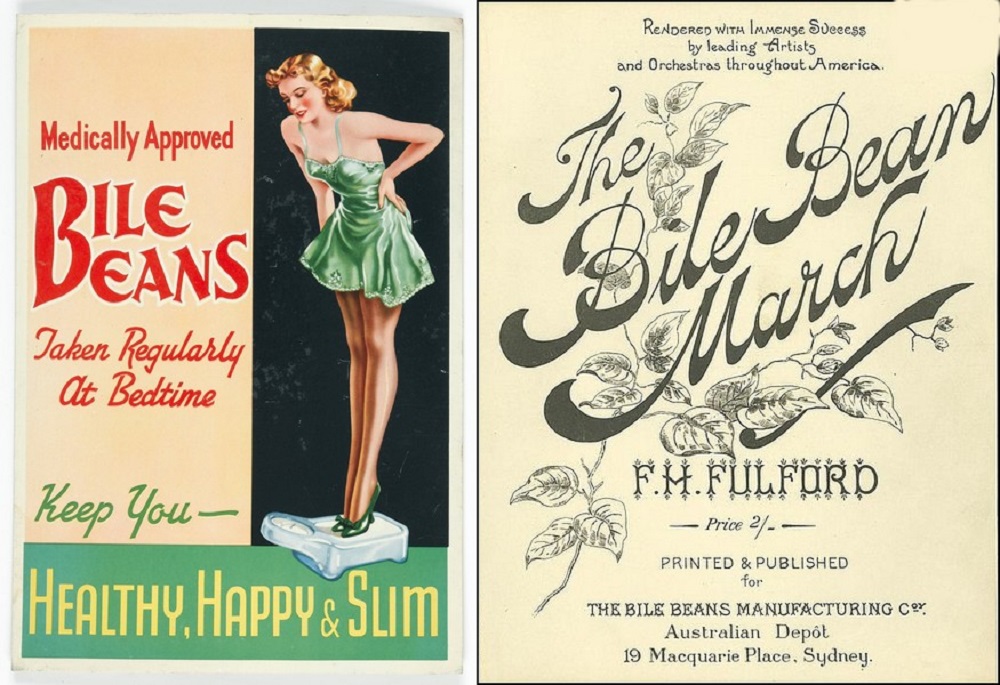

Aspro were sold in a distinctive cellophane strip (the inspiration for bubble packs perhaps?). Many regarded them as superior, purely because of the brand name, but their ingredients were actually the same as generic aspirin tablets. Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans!

Advertising drives would see men blitzing a neighbourhood with Bile Bean flyers containing testimonials from satisfied customers. One of the most extreme was from a mother who claimed she had been preparing her daughter’s grave clothes, just prior to said daughter’s recovery, due entirely to Bile beans!