In two words: Elijah Dixon.

The Manchester Bridgewater Freehold Land Society was formed in 1850 by Elijah and his colleagues, with the aim of allowing ordinary workers a chance to acquire land, for housing or allotments, away from the smoke and pollution of overcrowded industrial Manchester.

Despite the parliamentary Reform Act of 1832, most ordinary workers (and all women) were denied the vote unless they owned land, so having your name on one of the society’s plots also gave you this right.

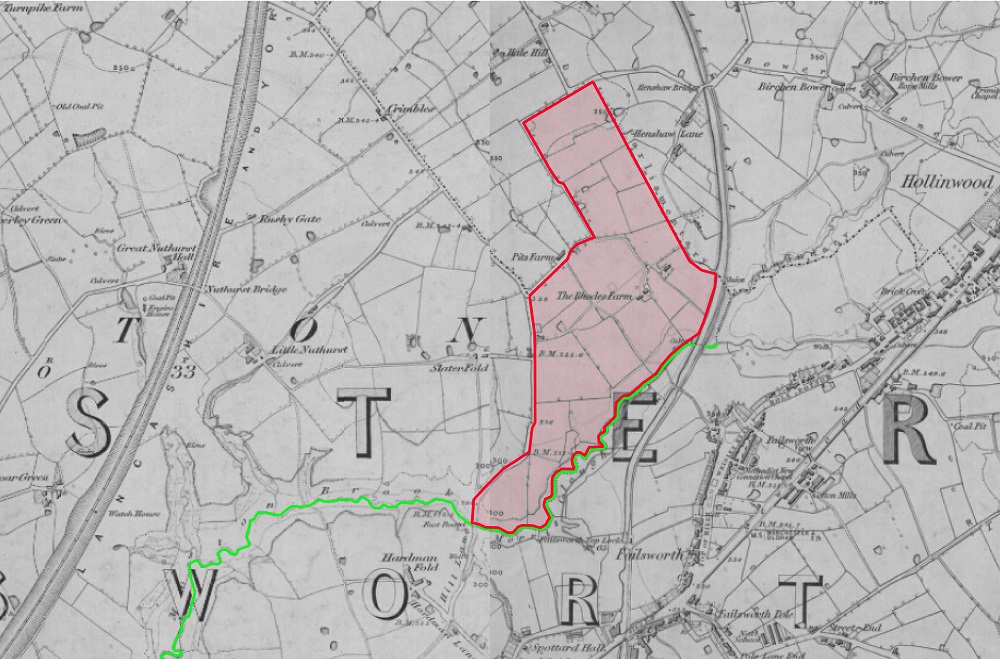

In March 1851, six holdings covering 57 acres at the “top end of Moston”, farmed by tenants of the Hilton family, of the medieval Great Nuthurst Hall, were purchased for £2,900 by the society, the aim being to divide the land into 230 plots. A plot could be bought through a loan, paid off by a subscription of a few pence or shillings a week. Land schemes such as this were early versions of what became building societies. The top end of Moston in 1848, showing the original area purchased by the Society shaded pink. Moston Brook is highlighted in green.

The top end of Moston in 1848, showing the original area purchased by the Society shaded pink. Moston Brook is highlighted in green.

A further £5,000 was invested by the society in laying out new streets to serve the plots. An access road was formed from Hale Lane in Failsworth to replace a footpath, known as Morris Lane, across the Moston Brook, which formed the boundary (and still does). Morris Lane ran into Moston Lane (now ‘East’). The new road, connecting with Oldham Road, gave an easier route to Manchester, Oldham or beyond.

The brook was culverted and the hollow filled in to permit a road wide, level and firm enough to take carts and carriages into the estate at ‘New Moston’. The name chosen reflected Robert Owen’s model housing schemes such as New Lanark and New Harmony.

The access road was opened in 1853 and was soon followed by the laying-out of five streets: Dixon, Ricketts, Potts, Jones and Frost Streets. These were later renamed Belgrave, Parkfield, Northfield, Eastwood and – combined with the existing Scholes Lane, past Pitt’s Farm – Hawthorn Roads respectively.

By 1854, houses had begun to be built, some of the earliest surviving ones being Rose and Moss Cottages, Ivy Cottage and by 1863, a pair of cottages on Dixon Street, one of which was used as a beerhouse. By 1871 this was already named the New Moston Inn; in the twentieth century the two cottages were rebuilt and merged together as one. The New Moston Inn, originally two cottages dating from 1863 or earlier, seen here in 1905.

The New Moston Inn, originally two cottages dating from 1863 or earlier, seen here in 1905.

Around 1870, Elijah Dixon himself moved to a house on Ricketts St (Vine House) from Newton Heath, where he had lived for many years, next to his match works and timber yard. He died at Vine House in 1876, but his daughter and grand-daughter continued the line right up to 1940.

There was little change after Elijah’s death, until Moston and New Moston became part of Manchester in 1890. Many little-used plots began to be sold to developers, and the next twenty years or so saw a massive expansion of housing, both within the original area, with the addition of side-streets and avenues, and beyond, as neighbouring farms were gradually sold off.

Schools were built on what had been Brown’s Farm, Slater Fold Farm gave way to Nuthurst Road, the park and the avenues around Hazeldene Road, and Crimbles Farm, the last to go, enabled further expansion along Moston Lane, extending right up to the Chadderton boundary.

From the 1920s onwards, the building of Broadway spurred further expansion, such as the estates around West Avenue and Chatwood Road: New Moston is now much bigger than the original “top end of Moston”.

Elijah Dixon’s story, of lifelong social justice campaigning and his parallel industrial success, has just been published by Pen and Sword Books of Barnsley (details on the link below):-

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Beyond-Peterloo-Paperback/p/15101

The authors will be giving a talk to the Newton Heath History Society on Tuesday, 24 July 2018 at 1:30pm, at the Heathfield Resource Centre, off Mitchell St, Newton Heath.

The author, aged about four, in the back yard of 5 Hanson Road, Moston.

The author, aged about four, in the back yard of 5 Hanson Road, Moston. Mum crossing Egbert Street near Langworthy Road in 1940. Mrs Mazza’s was the shop on the left.

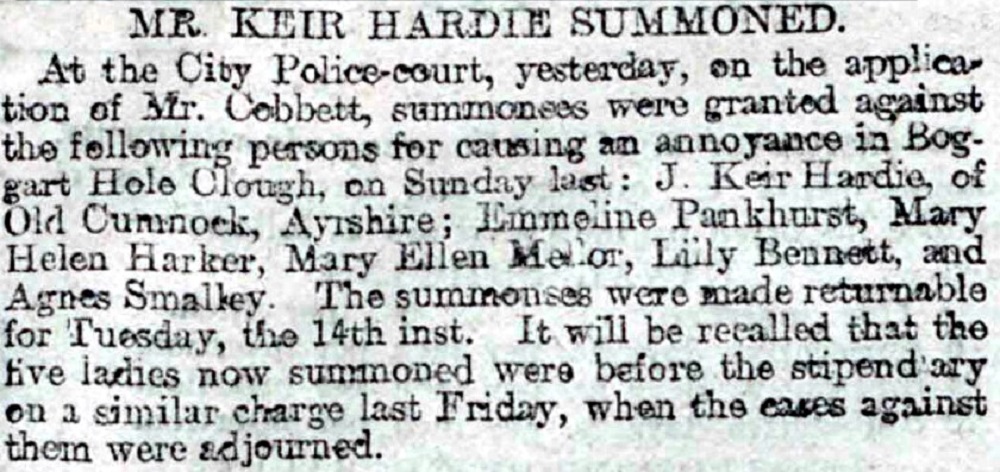

Mum crossing Egbert Street near Langworthy Road in 1940. Mrs Mazza’s was the shop on the left. Short article in the Manchester Courier, 9 July 1896

Short article in the Manchester Courier, 9 July 1896  Location of the former drinking fountain and refreshment rooms in Boggart Hole Clough, possibly the site referred to for the 1906 meeting

Location of the former drinking fountain and refreshment rooms in Boggart Hole Clough, possibly the site referred to for the 1906 meeting