Brownsfield Mill, by the Rochdale canal just off Great Ancoats Street, was built in 1820-5 as a spinning mill, but by the 1880s was already home to various small traders, making umbrellas, prams and other items. One such trader was William Payne, a wood-turner and chair maker originally from Berkshire, who settled there in 1889. Another was Humphrey Verdon Roe, who made surgical dressings and “Bull’s Eye” braces.

In the early 1900s, Humphrey let his younger brother, Edwin Alliott (who always preferred his second name) use his workshop for making experimental model aeroplanes, and later full-sized ones, William Payne often supplying the timber. William’s grandson, Jack Whitehouse, would occasionally hang around his grandad’s workshop, and many years later recalled Alliott as a very friendly young man, asking how he was getting on at school, and so on.

With help from his brother, in 1909 Alliott founded a company that was to become world-famous: A.V.Roe & Co, shortened to AVRO. Some of his early designs, including the “Bull’s Eye” triplane, which was the first successful all-British aeroplane, were fabricated in Ancoats. After being disassembled they were taken by horse and cart to London Road station, to be sent by train to places like Brooklands for assembly and testing.

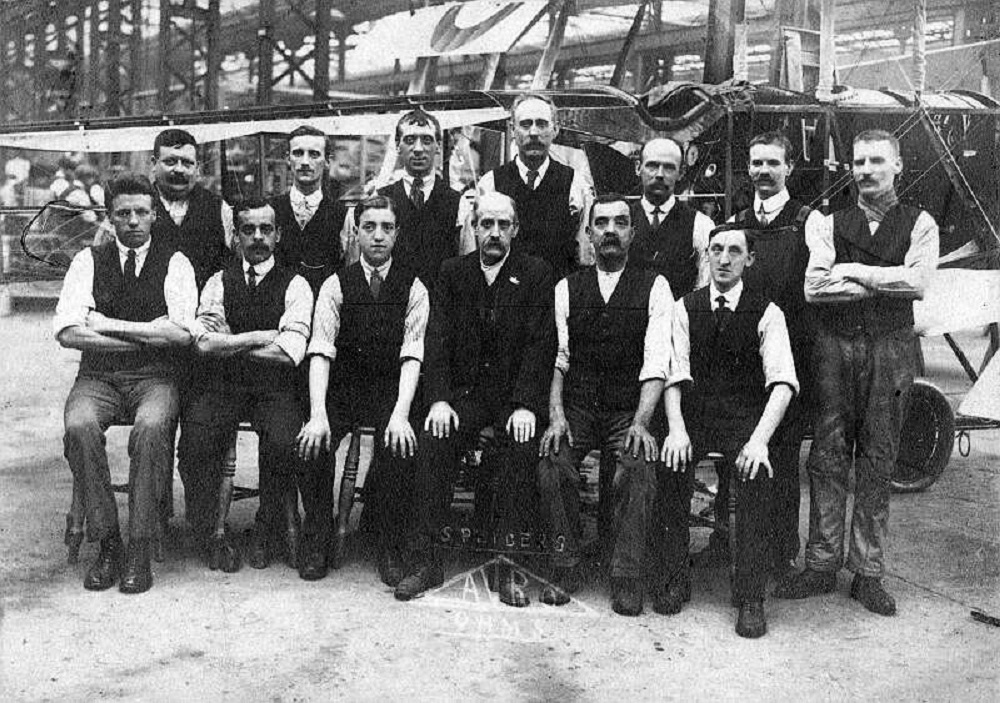

In 1910, the firm moved to larger premises at Clifton Street, Miles Platting. By then, young Jack had left school and found work on the railway, but Alliott offered him a job as a wire splicer: early multi-wing planes needed a lot of wire bracing, to give strength while keeping the weight down. Three years later an even larger works at Newton Heath was acquired, at the corner of Briscoe Lane and Ten Acres Lane, in an extension originally built for Mather and Platt.

The First World War, of course, established Avro as major aircraft designers and manufacturers, and the experience Jack gained with them led to his being recruited into the Royal Flying Corps as a rigger, making netting and other ropework for reconnaissance balloons, which were still very much in vogue. After the war, he was offered his old job back at Avro, but said he preferred being in the open air. He went back to the railway, first as a shunter and eventually as a goods guard.

Avro’s went from strength to strength, with premises at Woodford, Yeadon and Hamble being used at various times. In 1939 another huge works was built at Greengate, Chadderton, although the Newton Heath works was retained until 1947. One of the best-known aircraft of the Second World War, the Avro Lancaster, was designed here, around half of the 7,000 built coming from Chadderton. Another famous design followed just after the war: the Vulcan bomber, also designed at Greengate.

AVRO became part of Hawker Siddeley Aviation in 1963, during which period my uncle, Albert Robinson, worked in the offices at Chadderton. In 1977, the year he retired, the merged company was acquired by British Aerospace (later BAe Systems), who continued making aviation equipment until 2011.

I have not discovered what became of the Miles Platting works, but the other three buildings mentioned are still standing. Brownsfield Mill, after many years housing small businesses, is now an apartment block. The Briscoe Lane works, once used by the Co-operative Wholesale Society as a repair depot for their vehicle fleet, acts as a clothing warehouse, and the huge Chadderton plant is now home to Mono Pumps and Kitbag Ltd (sports clothing).

The Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester has an example of a “Bull’s Eye” triplane, although this is actually a replica, built from original drawings in 1964 for the film “Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines”.

In the 1950s, my grandad was interviewed by a reporter from the Manchester Evening News, recalling the pioneering days in Ancoats, so perhaps I should let him have the last word:

“Those machines looked for all the world like boxes on wheels, but we thought they were wonderfully up-to-date then.”

———————

A much more complete history of AVRO, its sites and products, can be found at their heritage centre in Woodford, Cheshire. Click here to view their website.

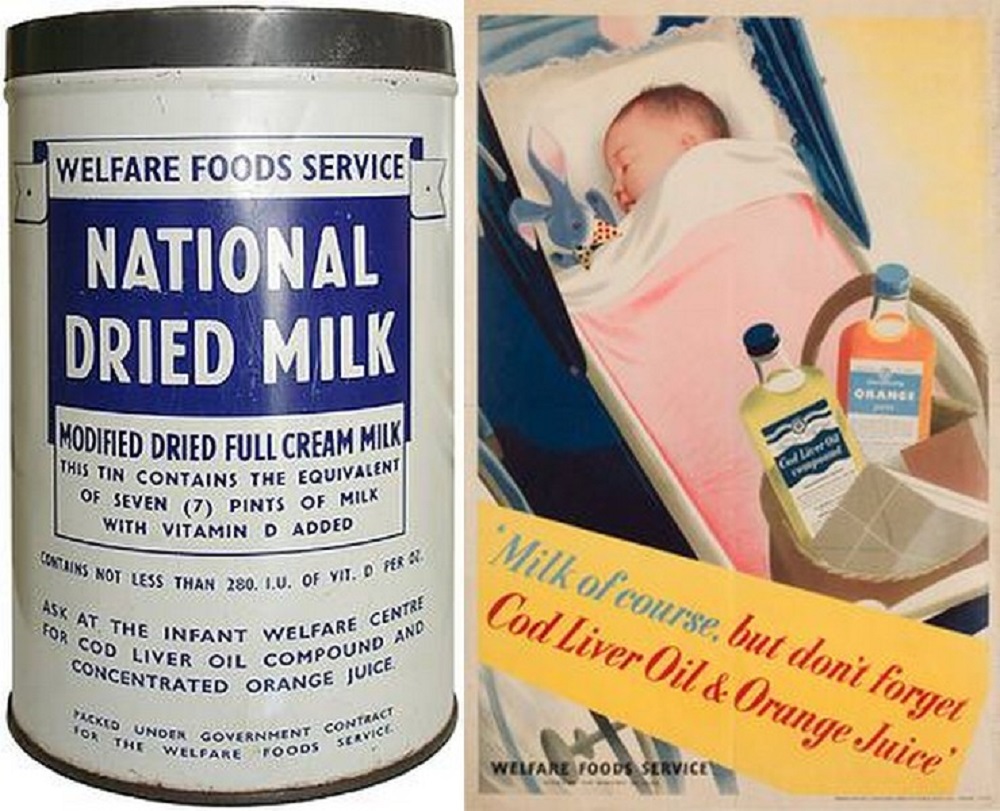

Even when coal ceased to be rationed, the supply often ran out before the next delivery. Consequently, to survive the privations, new-borns had to be toughened up from day one.

Even when coal ceased to be rationed, the supply often ran out before the next delivery. Consequently, to survive the privations, new-borns had to be toughened up from day one. Even when a house had a bathroom, lack of heating meant babies were often bathed in a large pot sink in the warm kitchen. A mother whose baby wasn’t wearing wool next to the skin, with its little bottom plastered in zinc and castor oil, would make herself the talk of the Welfare clinic.

Even when a house had a bathroom, lack of heating meant babies were often bathed in a large pot sink in the warm kitchen. A mother whose baby wasn’t wearing wool next to the skin, with its little bottom plastered in zinc and castor oil, would make herself the talk of the Welfare clinic. Unlike many fathers of the time, dad could change a nappy, though his method was unorthodox. He was also happy to baby-sit while mum had a night out at the pictures with my grandparents. One night, following a 12-hour shift on GPO ‘Christmas pressure’, he settled himself to listen to Saturday Night Theatre with his tired feet in a bowl of water. There was a scream, and dad was halfway up the stairs before realising it came from the wireless rather than my cot. Mum arrived home to find him sheepishly mopping the sopping carpet.

Unlike many fathers of the time, dad could change a nappy, though his method was unorthodox. He was also happy to baby-sit while mum had a night out at the pictures with my grandparents. One night, following a 12-hour shift on GPO ‘Christmas pressure’, he settled himself to listen to Saturday Night Theatre with his tired feet in a bowl of water. There was a scream, and dad was halfway up the stairs before realising it came from the wireless rather than my cot. Mum arrived home to find him sheepishly mopping the sopping carpet. The most traditional gift for new-borns was a teddy bear. Dad won mine at a fair before I was born. I would describe Ted’s appearance as unique rather than scary, but for the sake of persons with a nervous disposition, his picture has been withheld.

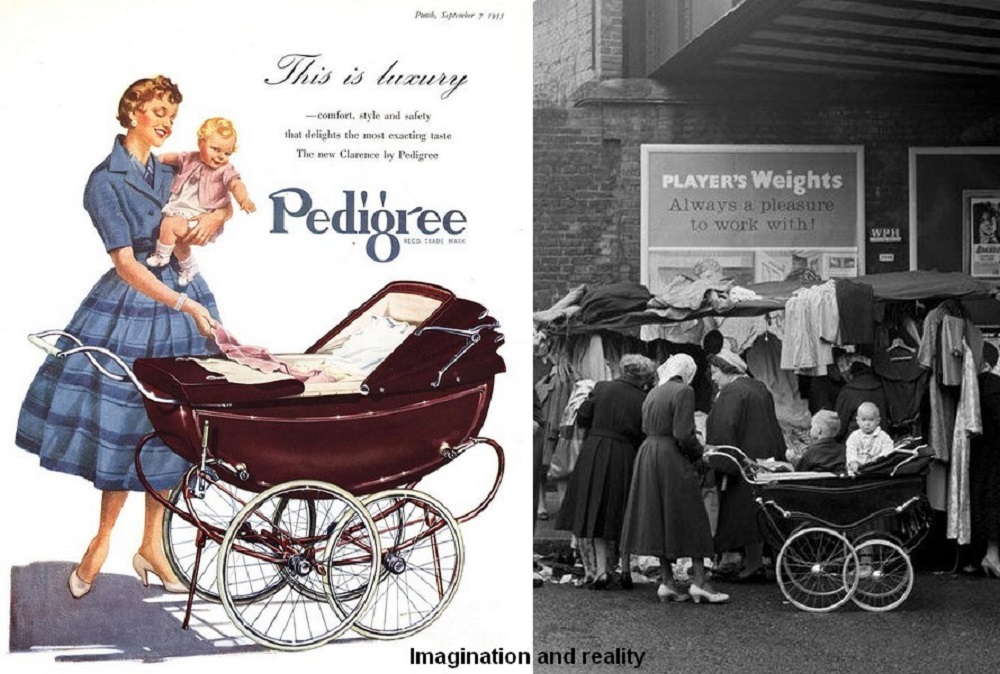

The most traditional gift for new-borns was a teddy bear. Dad won mine at a fair before I was born. I would describe Ted’s appearance as unique rather than scary, but for the sake of persons with a nervous disposition, his picture has been withheld. Children stayed in their prams far longer back then. By removing some of the base panels, an older child could sit upright with the rest of the ‘bilge’ being utilised for the shopping.

Children stayed in their prams far longer back then. By removing some of the base panels, an older child could sit upright with the rest of the ‘bilge’ being utilised for the shopping. Today’s all-terrain pushchairs and ergonomic baby seats are all very well, but as a child, I would have traded the lot for a bottle of that concentrated orange juice from ‘the Welfare’.

Today’s all-terrain pushchairs and ergonomic baby seats are all very well, but as a child, I would have traded the lot for a bottle of that concentrated orange juice from ‘the Welfare’. One year Father Christmas brought me a small chipboard kitchen dresser, probably made by someone my dad knew. I loved it, despite its ghastly shade of pink (war surplus paint perhaps?). The painted tin tea set from my grandparents sat on the open shelves, while jigsaws and games could be stored in the bottom cupboard.

One year Father Christmas brought me a small chipboard kitchen dresser, probably made by someone my dad knew. I loved it, despite its ghastly shade of pink (war surplus paint perhaps?). The painted tin tea set from my grandparents sat on the open shelves, while jigsaws and games could be stored in the bottom cupboard. Whatever the current craze, it was sure to appear on most Christmas lists. The ones I remember best were yo-yos, hula hoops and roller skates. Maybe it was because I was shy, but it mattered very much that my present of desire was exactly ‘right’.

Whatever the current craze, it was sure to appear on most Christmas lists. The ones I remember best were yo-yos, hula hoops and roller skates. Maybe it was because I was shy, but it mattered very much that my present of desire was exactly ‘right’. A compendium of games was up market, but sets of draughts, snakes and ladders, Ludo or even tiddly-winks were not to be sniffed at. Later in the decade, board games like Monopoly and Cluedo came along, but they were expensive, so stockings were more likely to contain a pack of cards.

A compendium of games was up market, but sets of draughts, snakes and ladders, Ludo or even tiddly-winks were not to be sniffed at. Later in the decade, board games like Monopoly and Cluedo came along, but they were expensive, so stockings were more likely to contain a pack of cards. I invariably got one of the things specified on that list (or lists) I sent up the chimney. My parents would have been astounded to learn I felt the best bit of Christmas morning was opening my stocking. I loved those catch penny items such as chalks, crayons, puzzles, books and chocolate money, sold as stocking fillers.

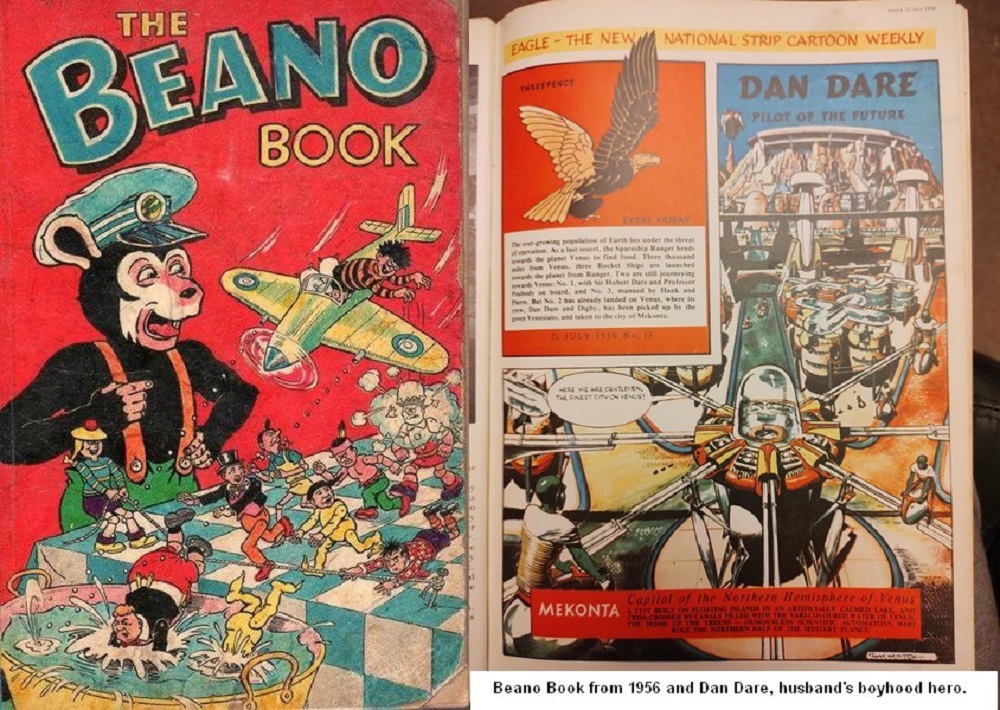

I invariably got one of the things specified on that list (or lists) I sent up the chimney. My parents would have been astounded to learn I felt the best bit of Christmas morning was opening my stocking. I loved those catch penny items such as chalks, crayons, puzzles, books and chocolate money, sold as stocking fillers.