Our own locality was generally the place we shopped, so a trip to ‘town’ was rather special. Some trolley buses still ran on the 88 route, and if I could persuade mum to go upstairs, it made the trip even better.

Although logic tells me it isn’t true, it was always a winter afternoon when we were in town.

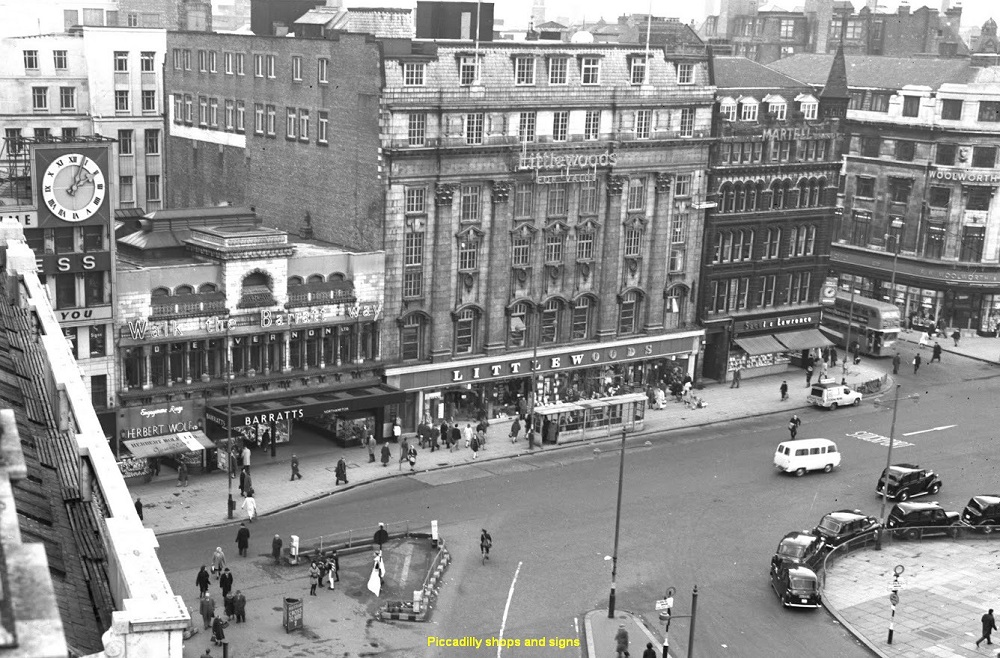

The bomb site on one side of Piccadilly was a legacy of the Christmas blitz of 1941. However the gardens remained the town centre to us, and the illuminated signs on the opposite side kept our eyes averted from the devastation. Colourful neon lights exhorted us to ‘walk the Barratt way’, and a huge clock announced Guinness was good for us. In those pre-mobile phone days, many people used the flashing Mother’s Pride sign as a designated meeting point. And to keep you occupied while waiting, there was a newsfeed spooling across the building facades on a rolling display. There must have been traffic noise, but I remember the predominant sound as the Murmuration of thousands of starlings roosting on high window sills.

There must have been traffic noise, but I remember the predominant sound as the Murmuration of thousands of starlings roosting on high window sills.

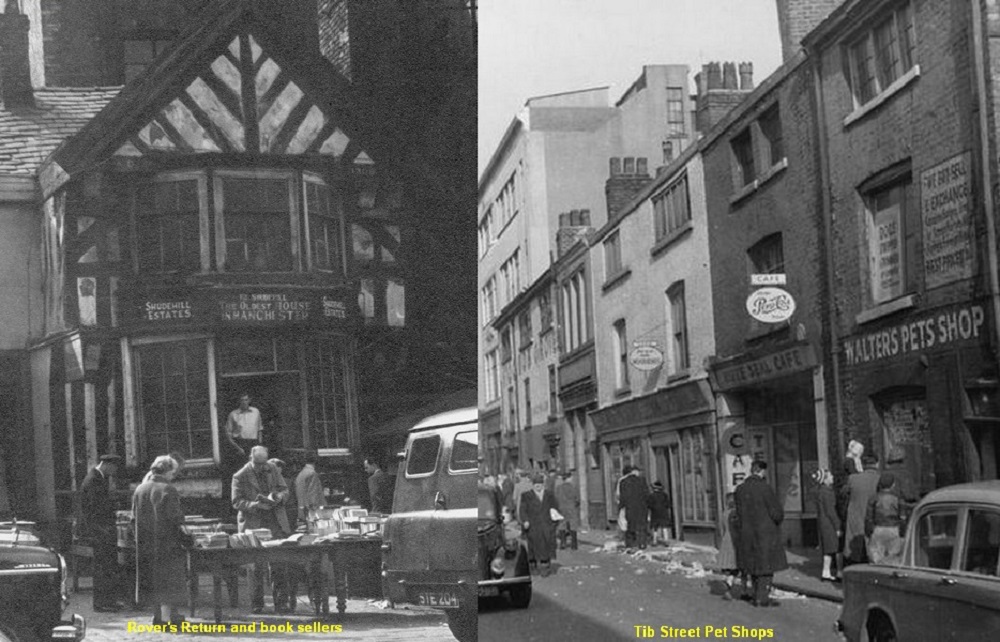

In those days, whatever the size, shops each had some USP (unique selling point) to tempt us inside. Whether you were looking for a kitten or an alto saxophone, Tib Street was the place to go. It was just one of the many narrow back streets teeming with shops supplying items not stocked by the larger stores. However the department stores’ magnificent window displays acted like a magnet. Once inside, the interiors were a symphony of polished wood, brass, and occasionally marble. Even the toilet facilities seemed opulent. With their own banks, cafes, and hairdressing salons, the stores were a sophisticated microcosm of the streets surrounding them.

However the department stores’ magnificent window displays acted like a magnet. Once inside, the interiors were a symphony of polished wood, brass, and occasionally marble. Even the toilet facilities seemed opulent. With their own banks, cafes, and hairdressing salons, the stores were a sophisticated microcosm of the streets surrounding them.

I liked going into Henry’s because it had a moving staircase (escalator). It’s difficult to imagine, but travelling in a lift was then still something of a novelty. A uniformed man (often a disabled war veteran) operated the switches whilst calling out each floor’s merchandise.

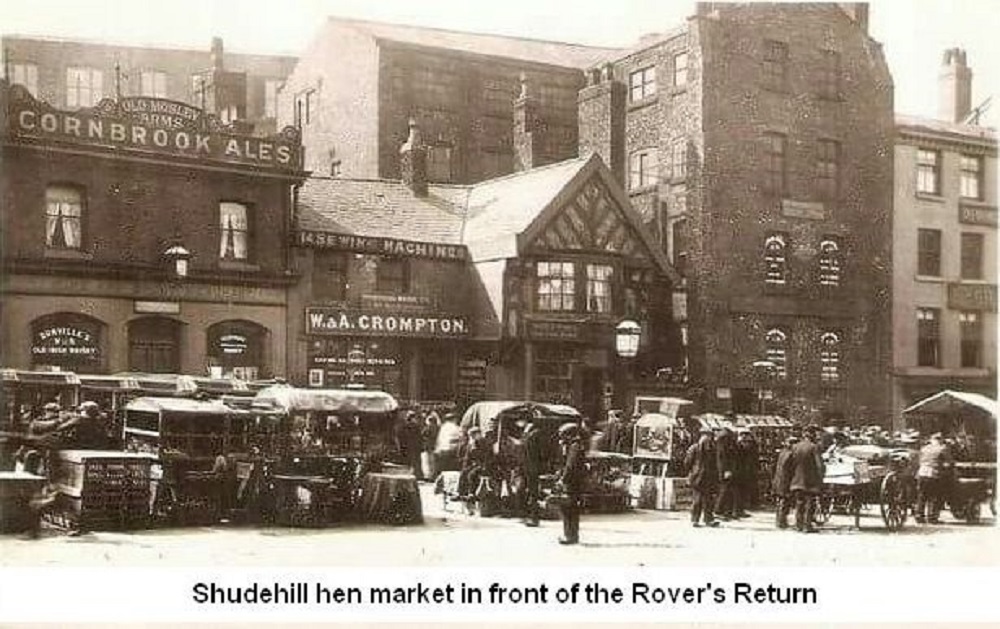

In the fifties, to find a street market and an ancient black and white building standing alongside Georgian warehouses, or a modern office block, was not unusual. It was simply a glimpse into the different phases of Manchester’s commercial history.

If our elderly hens needed replacing, we headed for Shudehill market on Sunday morning. I recall sitting on the steps of an old building, once the Rovers Return Inn, while granddad checked out each bird. Finding a building of such antiquity in the middle of ‘town’ was what kick-started my interest in the past. Another historical landmark I liked was the statuary on one of the cotton offices. Two figures I called ‘the dirty ladies’ reclined across the top of an ornate portico. My name for them didn’t refer to their state of undress, but rather the blackening caused by the smoke from nearby mill chimneys. Henry’s was about as far down Market Street as we usually ventured. We had Woolworths, C&A, Affleck & Brown, M&S and Littlewoods, not to mention as many shoe shops as you could wish for, on Oldham Street and Piccadilly.

Henry’s was about as far down Market Street as we usually ventured. We had Woolworths, C&A, Affleck & Brown, M&S and Littlewoods, not to mention as many shoe shops as you could wish for, on Oldham Street and Piccadilly.

The other outer limit for shopping was New Cross, once part of the area known as Little Italy. Many Italian street musicians lived there in the 1800s, so it seems appropriate it was the place I last heard a barrel organ. Masons was one of the largest shops on the Oldham Road side of Victoria Square (aka the Dwellings).

While my parents were busy choosing oilcloth (linoleum), I was spellbound by the organ grinder doing his stuff at the Bengal Street entrance to ‘the Dwellings’. With no access to recorded music, little girls like my nana danced around barrel organs. I like to imagine the elderly flat dwellers sighing as they were transported back to childhood days. By the fifties, Manchester’s motto seemed to be ‘progress at any price’. That apparently meant the sacrifice of the Rovers Return Inn, and the multiplicity of small businesses trading out of buildings up to 200 years old, which effectively drained the life from the area now known as the Northern Quarter.

By the fifties, Manchester’s motto seemed to be ‘progress at any price’. That apparently meant the sacrifice of the Rovers Return Inn, and the multiplicity of small businesses trading out of buildings up to 200 years old, which effectively drained the life from the area now known as the Northern Quarter.

Bricks and mortar were not the only thing which disappeared when small businesses and workshops were demolished. We lost the irreplaceable skills of rag trade workers, manufacturing jewellers, tailors, picture framers and ticket writers. And suddenly there was nowhere to get shoe, umbrella, watch and electrical repairs done.

Today not even a ride on a trolley bus could get me excited about going to ‘town’.

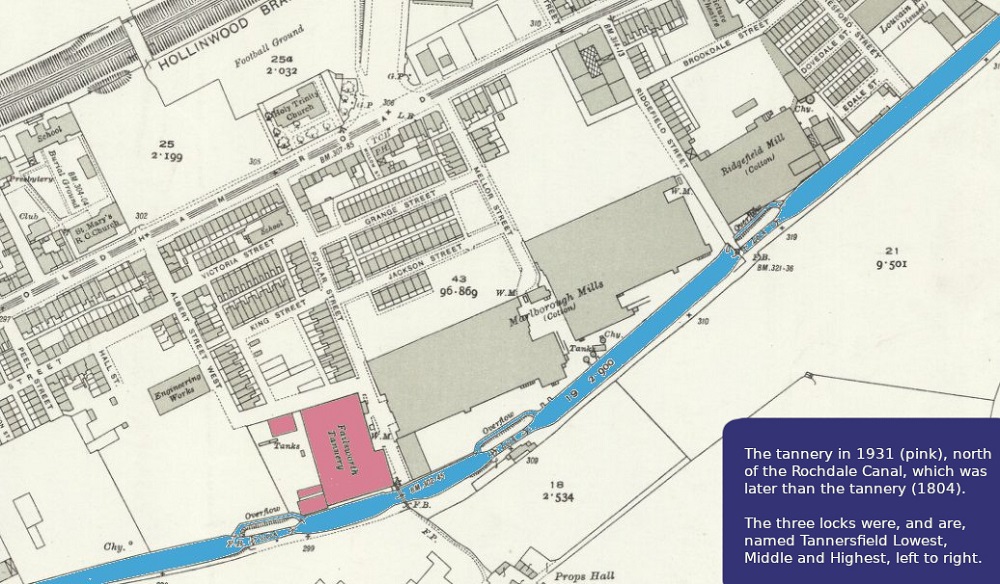

With the industrial revolution came a massive increase in demand for leather, not only for shoes and clothing for the growing population, but for the accoutrements of the steam age: belts to drive machinery, protective aprons, masks and gloves, piston glands and all manner of other bits and bobs. Thomas Kershaw was named as the tanner in Failsworth, when he married in October 1769, and took on an apprentice in 1771.

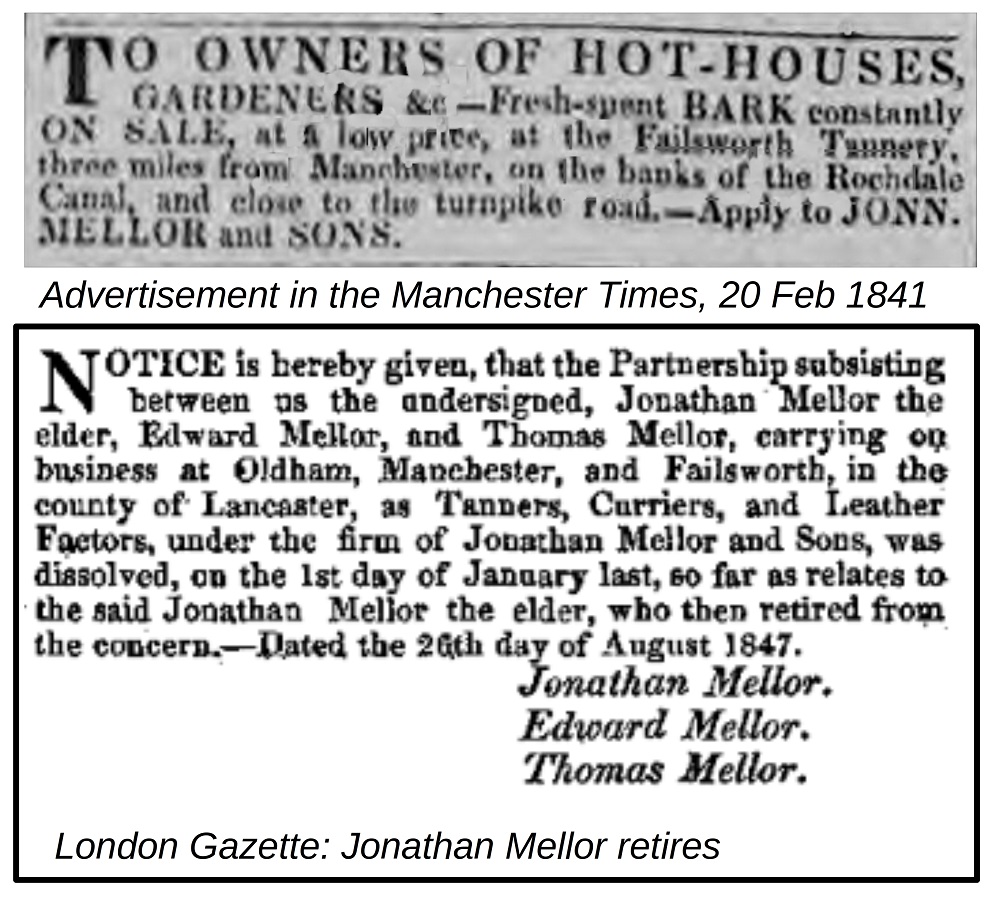

With the industrial revolution came a massive increase in demand for leather, not only for shoes and clothing for the growing population, but for the accoutrements of the steam age: belts to drive machinery, protective aprons, masks and gloves, piston glands and all manner of other bits and bobs. Thomas Kershaw was named as the tanner in Failsworth, when he married in October 1769, and took on an apprentice in 1771. Jonathan retired in 1847, leaving the tannery in the capable hands of his sons; he died two years later and was buried at Oldham parish church, where he had held a pew since 1842. Edward decided to concentrate on the mill interests in Rochdale, leaving Thomas in sole charge of the tannery from 1854. Unlike his father, who had resided on King St, Oldham up to his death, Thomas moved to Failsworth, living at Rich Field House, Dob Lane, and later becoming a J.P. and Poor Law Guardian.

Jonathan retired in 1847, leaving the tannery in the capable hands of his sons; he died two years later and was buried at Oldham parish church, where he had held a pew since 1842. Edward decided to concentrate on the mill interests in Rochdale, leaving Thomas in sole charge of the tannery from 1854. Unlike his father, who had resided on King St, Oldham up to his death, Thomas moved to Failsworth, living at Rich Field House, Dob Lane, and later becoming a J.P. and Poor Law Guardian. Around 1880, Thomas moved to Firs Hall, Failsworth, where he died in 1889, aged 81. Sir Edward Watkin (knighted in 1868) attended his funeral at Failsworth cemetery. His son, Robert, who had been born in Failsworth around 1853, took charge of the tannery, which then became “Robert Mellor Ltd”. In 1890, Robert married Eliza Melland of Bowdon, Cheshire, and moved to Disley.

Around 1880, Thomas moved to Firs Hall, Failsworth, where he died in 1889, aged 81. Sir Edward Watkin (knighted in 1868) attended his funeral at Failsworth cemetery. His son, Robert, who had been born in Failsworth around 1853, took charge of the tannery, which then became “Robert Mellor Ltd”. In 1890, Robert married Eliza Melland of Bowdon, Cheshire, and moved to Disley. The firm continued as Robert Mellor Ltd after his death and was listed as ‘sole-leather tanners’ in international directories, evidence of export as well as home markets. Another misfortune befell the firm when a fire broke out in the early hours of Saturday, 4 July 1914. The exact cause was never established, but it was reported that fifty firemen attended the blaze, which nevertheless destroyed most of the warehouse and around £12,000 worth of finished leather. Bystanders also said a large number of rats were seen dashing out and jumping into the canal!

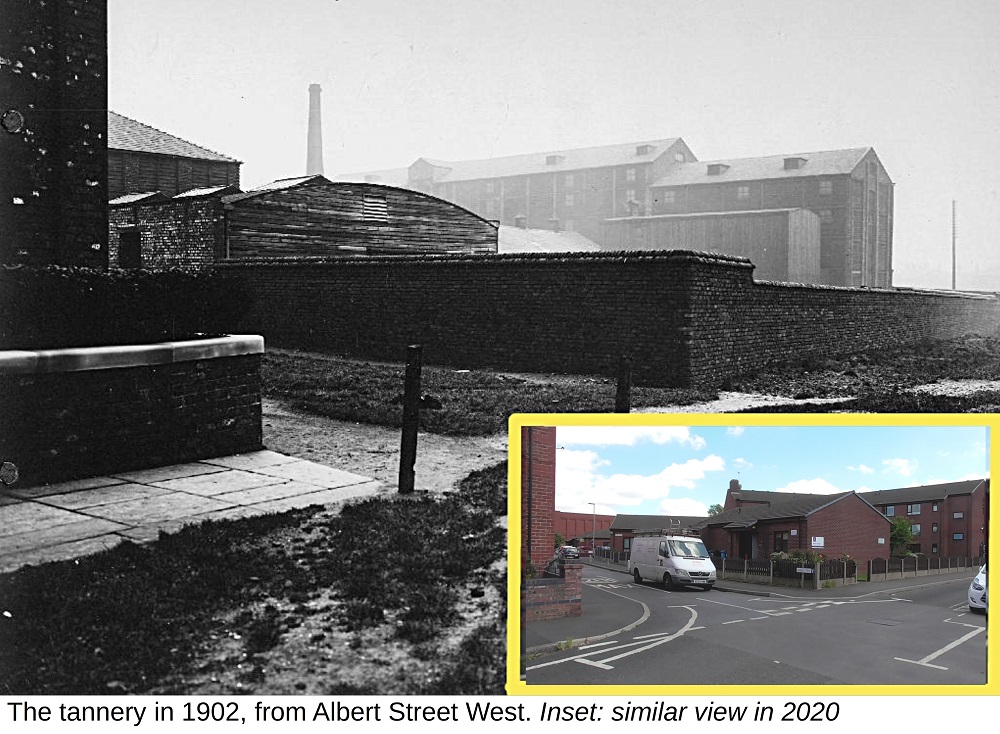

The firm continued as Robert Mellor Ltd after his death and was listed as ‘sole-leather tanners’ in international directories, evidence of export as well as home markets. Another misfortune befell the firm when a fire broke out in the early hours of Saturday, 4 July 1914. The exact cause was never established, but it was reported that fifty firemen attended the blaze, which nevertheless destroyed most of the warehouse and around £12,000 worth of finished leather. Bystanders also said a large number of rats were seen dashing out and jumping into the canal! The tannery continued to be listed in telephone books up to 1930, but appears to have closed by 1935. Nothing now remains: the Home Guard Club and wooden garages were built on the site in the 1960s, with bungalows and flats added later. The leather trade is still with us, of course, now utilising different, largely mechanised, processes, but there is still one traditional oak bark tannery at Colyton in Devon.

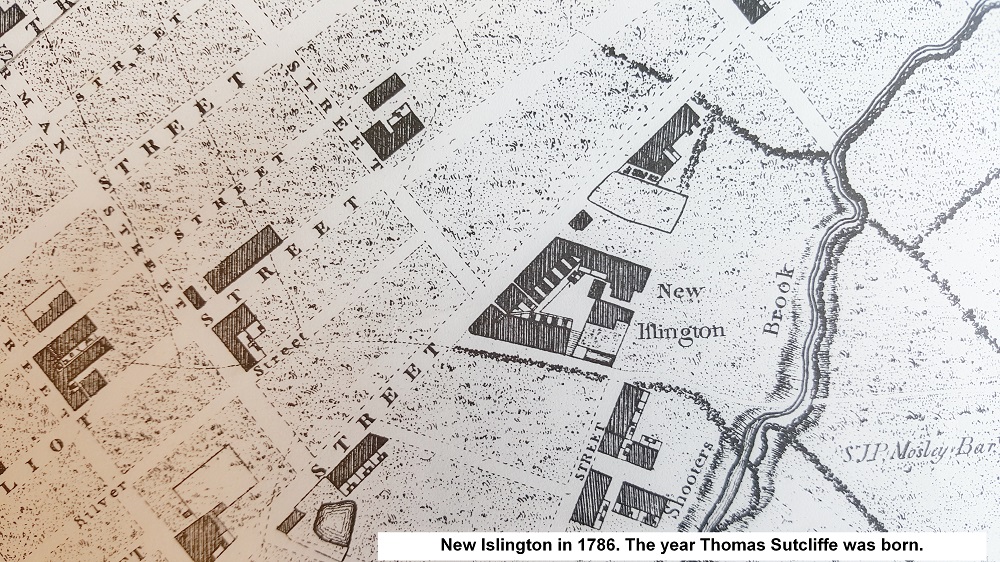

The tannery continued to be listed in telephone books up to 1930, but appears to have closed by 1935. Nothing now remains: the Home Guard Club and wooden garages were built on the site in the 1960s, with bungalows and flats added later. The leather trade is still with us, of course, now utilising different, largely mechanised, processes, but there is still one traditional oak bark tannery at Colyton in Devon. My 4 times great grandfather’s birth in 1786 coincided with the influx of country people seeking work in Manchester’s mills. The majority were casualties of mechanisation and newly introduced farming methods. Casual labour was replacing secure employment with a subsequent forfeiting of tied cottages.

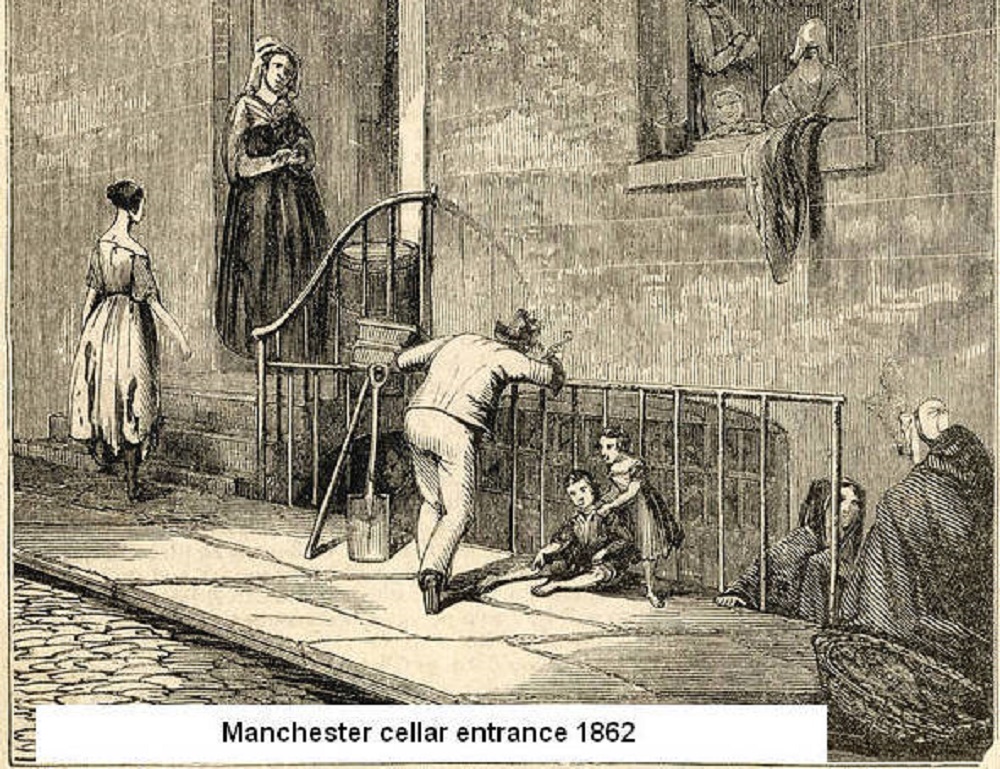

My 4 times great grandfather’s birth in 1786 coincided with the influx of country people seeking work in Manchester’s mills. The majority were casualties of mechanisation and newly introduced farming methods. Casual labour was replacing secure employment with a subsequent forfeiting of tied cottages. Many families were reduced to sharing turf huts erected on waste or common land with their livestock. But at the whim of a land owner, the turf huts could be pulled down, and the occupants driven beyond the parish boundaries.

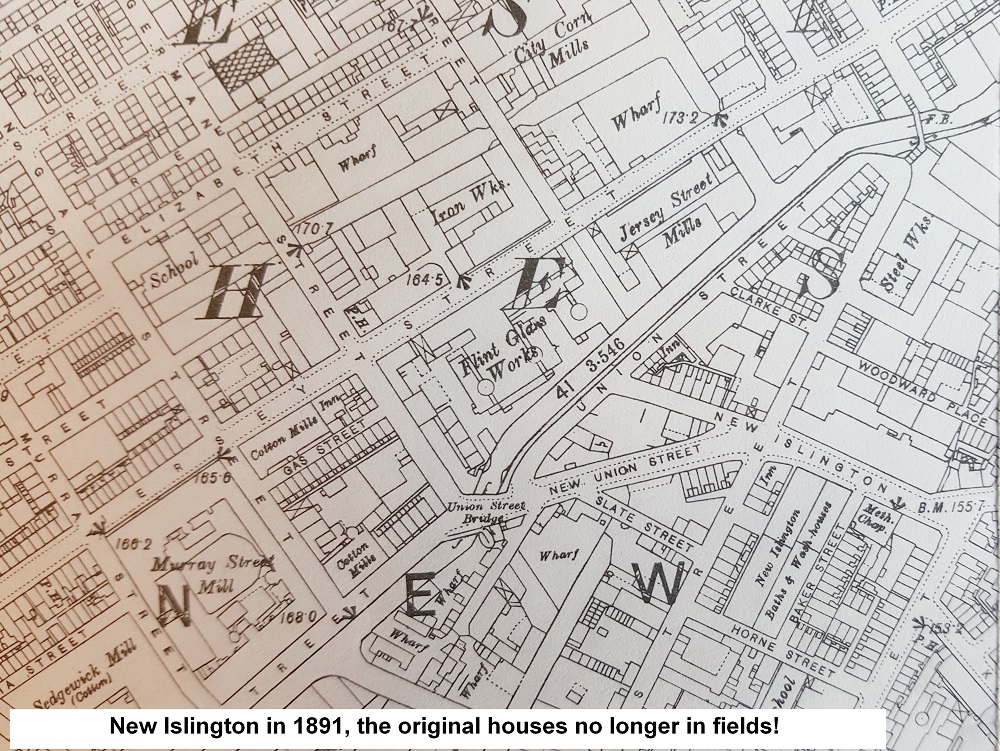

Many families were reduced to sharing turf huts erected on waste or common land with their livestock. But at the whim of a land owner, the turf huts could be pulled down, and the occupants driven beyond the parish boundaries. Central districts soon reached bursting point, and speculative builders turned their attention to Ancoats and Collyhurst.

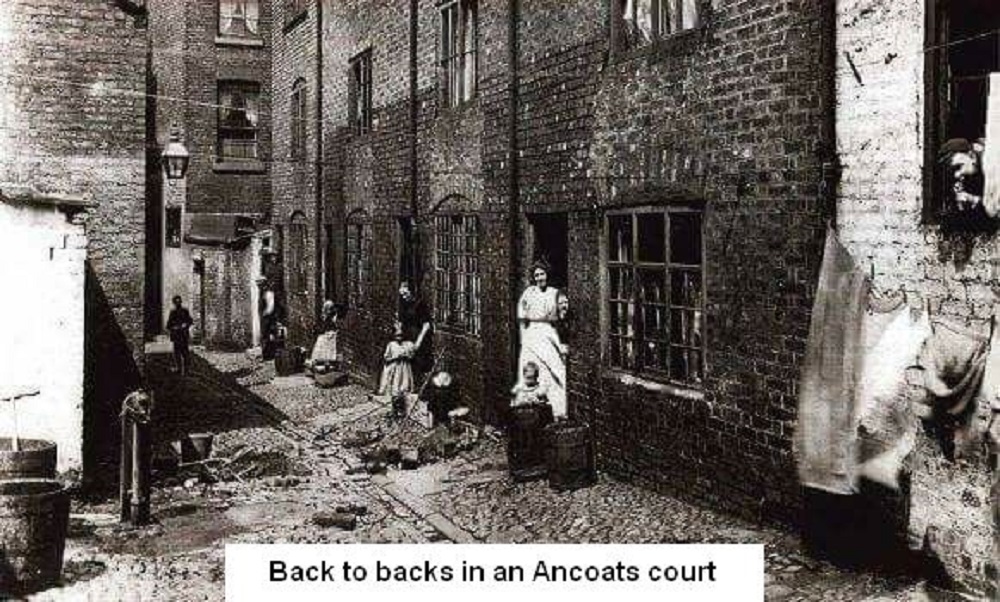

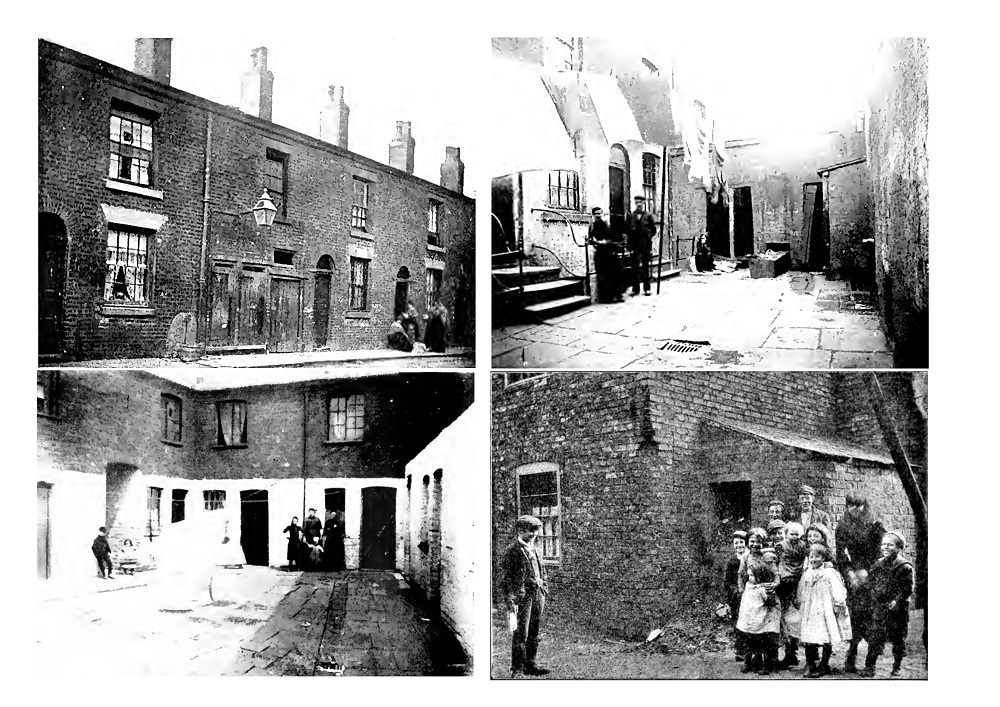

Central districts soon reached bursting point, and speculative builders turned their attention to Ancoats and Collyhurst. Primitive as these dwellings were, property owners soon realised that one up/one down terraces would yield more profit if they were constructed back-to-back (sharing a central wall).

Primitive as these dwellings were, property owners soon realised that one up/one down terraces would yield more profit if they were constructed back-to-back (sharing a central wall). Housing density was unprecedented, yet speculators were convinced still more profit could be squeezed from their investments. The solution they came up with was ‘closed courts’.

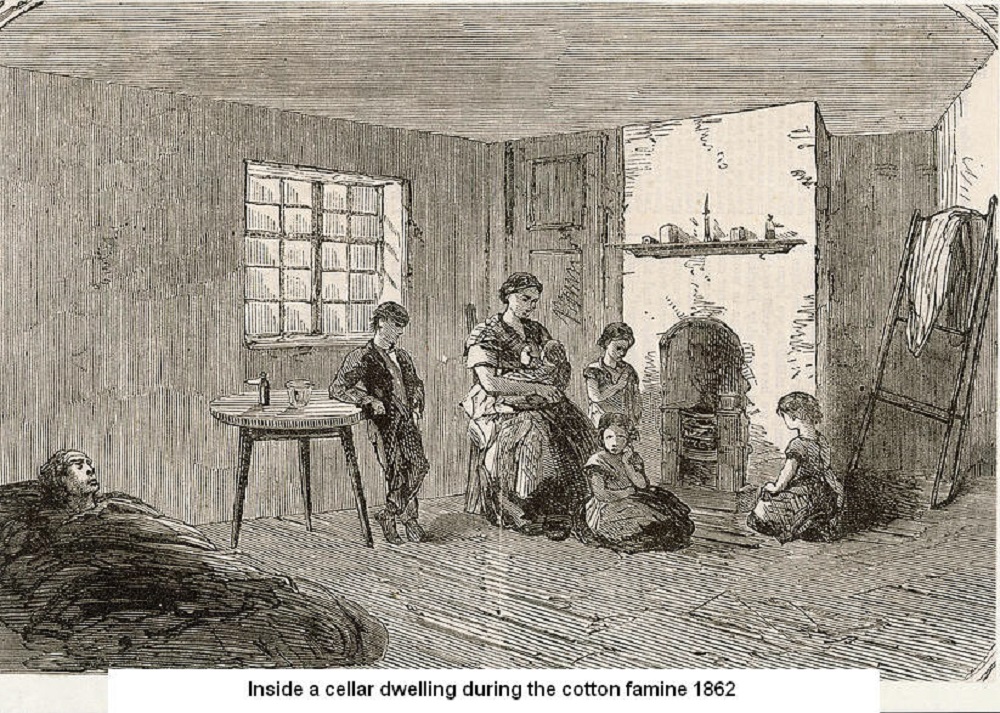

Housing density was unprecedented, yet speculators were convinced still more profit could be squeezed from their investments. The solution they came up with was ‘closed courts’. Access to the seven inter-connecting ‘closed courts’ was by covered ginnels, 3 to 4 foot wide. Hundreds of people in the seven courts were served by a single pump. It was situated in the 4 foot wide Kerr’s Court which had 5 one up/one down houses with cellars. Until the corporation’s bye laws were implemented in the last quarter of the century, no sanitary provision whatsoever existed in some of the courts.

Access to the seven inter-connecting ‘closed courts’ was by covered ginnels, 3 to 4 foot wide. Hundreds of people in the seven courts were served by a single pump. It was situated in the 4 foot wide Kerr’s Court which had 5 one up/one down houses with cellars. Until the corporation’s bye laws were implemented in the last quarter of the century, no sanitary provision whatsoever existed in some of the courts.