I was born in the legendary ‘terrible winter’ of 47. Even when coal ceased to be rationed, the supply often ran out before the next delivery. Consequently, to survive the privations, new-borns had to be toughened up from day one.

Even when coal ceased to be rationed, the supply often ran out before the next delivery. Consequently, to survive the privations, new-borns had to be toughened up from day one.

My mother used to pin me into the bedclothes of my cot, to prevent me getting my hands free during the night. Even with ice on the inside of windows, I never lost a single finger to frost bite, so it must have worked. However, it has left me with a phobia about having my arms confined.

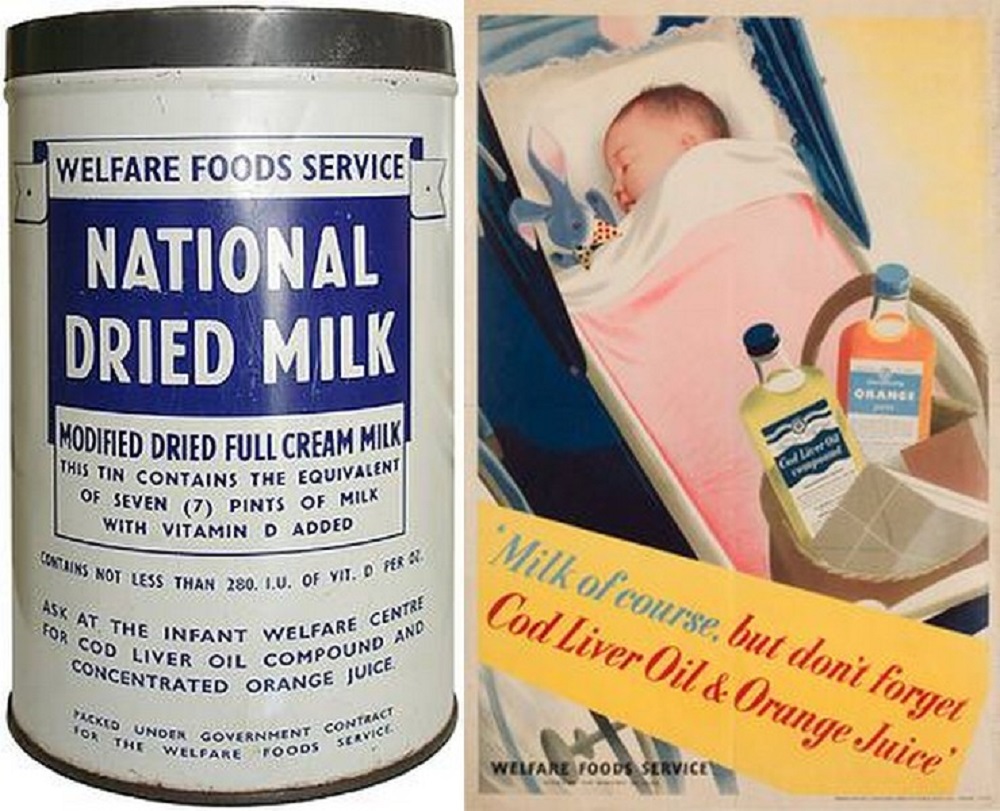

We were the Virol, rusks and National Dried Milk generation, when clothing substituted for the central heating lacking in our houses. Swaddling was out of date, but babies less than 5 lbs were kept in cotton wool jackets (not removed, even for washing) until the required weight was achieved. Even when a house had a bathroom, lack of heating meant babies were often bathed in a large pot sink in the warm kitchen. A mother whose baby wasn’t wearing wool next to the skin, with its little bottom plastered in zinc and castor oil, would make herself the talk of the Welfare clinic.

Even when a house had a bathroom, lack of heating meant babies were often bathed in a large pot sink in the warm kitchen. A mother whose baby wasn’t wearing wool next to the skin, with its little bottom plastered in zinc and castor oil, would make herself the talk of the Welfare clinic.

Terry nappies were expensive, and only came in one size – huge. They had to survive daily boil washes until the family’s youngest child was toilet trained. By the early fifties, most babies wore rubber pants, but knitting patterns for the ‘pilch’ (a natural wool garment worn over nappies) was still available.

Vest and nappy were covered by layers of winceyette, leaving the now globular-shaped baby to be topped off with something smart but impractical. The preference was for dresses, romper suits or the unisex leggings and matinee jackets with gender appropriate headgear. Unlike many fathers of the time, dad could change a nappy, though his method was unorthodox. He was also happy to baby-sit while mum had a night out at the pictures with my grandparents. One night, following a 12-hour shift on GPO ‘Christmas pressure’, he settled himself to listen to Saturday Night Theatre with his tired feet in a bowl of water. There was a scream, and dad was halfway up the stairs before realising it came from the wireless rather than my cot. Mum arrived home to find him sheepishly mopping the sopping carpet.

Unlike many fathers of the time, dad could change a nappy, though his method was unorthodox. He was also happy to baby-sit while mum had a night out at the pictures with my grandparents. One night, following a 12-hour shift on GPO ‘Christmas pressure’, he settled himself to listen to Saturday Night Theatre with his tired feet in a bowl of water. There was a scream, and dad was halfway up the stairs before realising it came from the wireless rather than my cot. Mum arrived home to find him sheepishly mopping the sopping carpet.

The presents babies received were like children of the past: seen but not heard. We had to be satisfied with the sound of rattles and humming tops, while today everything from a mobile to a potty plays a nursery rhyme or animal noise. The most traditional gift for new-borns was a teddy bear. Dad won mine at a fair before I was born. I would describe Ted’s appearance as unique rather than scary, but for the sake of persons with a nervous disposition, his picture has been withheld.

The most traditional gift for new-borns was a teddy bear. Dad won mine at a fair before I was born. I would describe Ted’s appearance as unique rather than scary, but for the sake of persons with a nervous disposition, his picture has been withheld.

None of my surviving toys has ever been washed. With children’s propensity for putting everything straight into their mouths, it’s amazing so little consideration was given to hygiene and safety in the past.

Another inexplicable thing is the adult conspiracy that kept children believing babies materialised from nowhere. My own first intimation there was ‘summat up’, was getting home from afternoon school to find a ‘little stranger’ asleep in my old cot.

Prior to my sister’s arrival, living alongside me were 4 adults in a small council house. If she had been born in the 21st century, her bath, bouncy chair, Moses basket with stand and the myriad other essentials she couldn’t have done without, would have necessitated an extension.

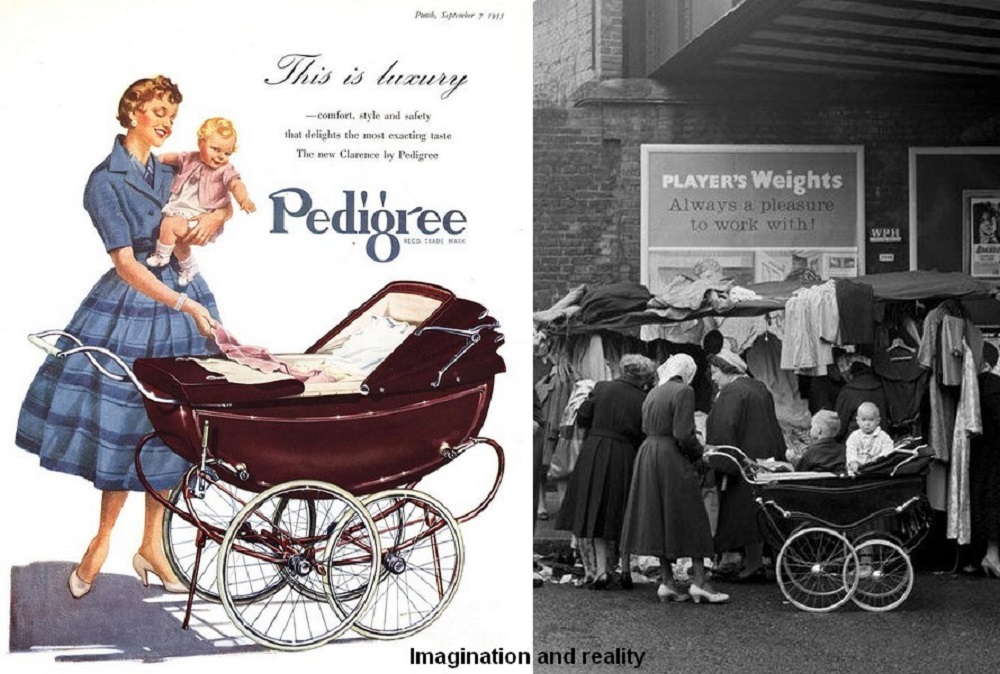

Unoccupied coach-built prams were a menace in narrow lobbies and passages. But no self-respecting mother would fail to put the swanky pram outside for her baby to get its daily dose of ‘fresh air’. Children stayed in their prams far longer back then. By removing some of the base panels, an older child could sit upright with the rest of the ‘bilge’ being utilised for the shopping.

Children stayed in their prams far longer back then. By removing some of the base panels, an older child could sit upright with the rest of the ‘bilge’ being utilised for the shopping.

Tumbles from prams must have been common before harnesses were fitted as standard. Strangely, when there were far fewer speeding motor vehicles, more toddlers were to be seen wearing reins looped over the arm of a parent or responsible sibling. Today’s all-terrain pushchairs and ergonomic baby seats are all very well, but as a child, I would have traded the lot for a bottle of that concentrated orange juice from ‘the Welfare’.

Today’s all-terrain pushchairs and ergonomic baby seats are all very well, but as a child, I would have traded the lot for a bottle of that concentrated orange juice from ‘the Welfare’.

One year Father Christmas brought me a small chipboard kitchen dresser, probably made by someone my dad knew. I loved it, despite its ghastly shade of pink (war surplus paint perhaps?). The painted tin tea set from my grandparents sat on the open shelves, while jigsaws and games could be stored in the bottom cupboard.

One year Father Christmas brought me a small chipboard kitchen dresser, probably made by someone my dad knew. I loved it, despite its ghastly shade of pink (war surplus paint perhaps?). The painted tin tea set from my grandparents sat on the open shelves, while jigsaws and games could be stored in the bottom cupboard. Whatever the current craze, it was sure to appear on most Christmas lists. The ones I remember best were yo-yos, hula hoops and roller skates. Maybe it was because I was shy, but it mattered very much that my present of desire was exactly ‘right’.

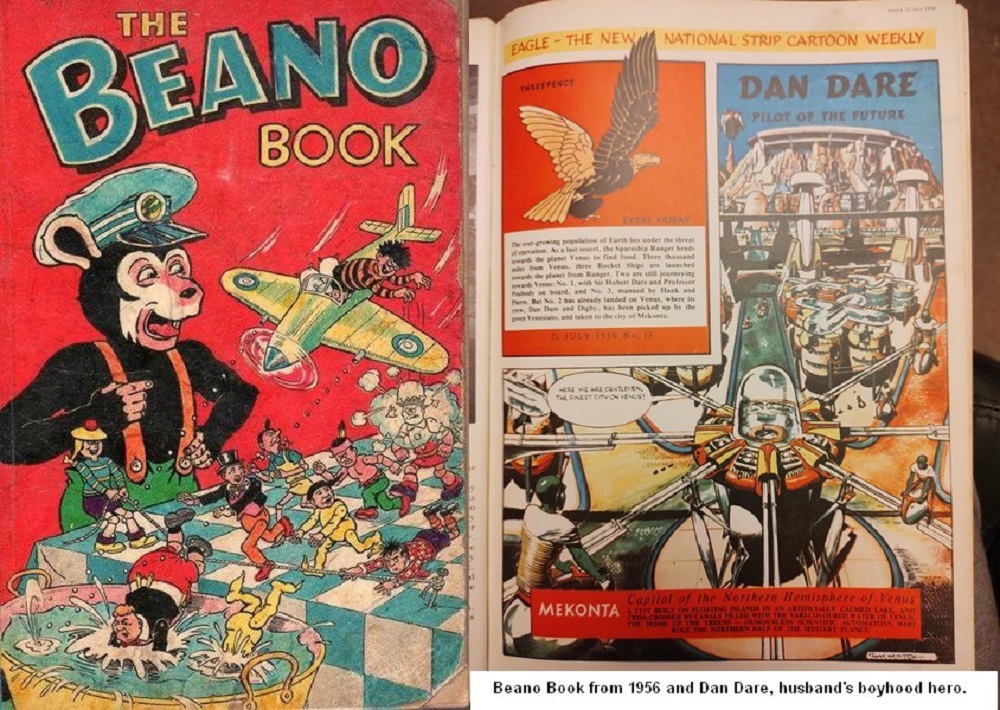

Whatever the current craze, it was sure to appear on most Christmas lists. The ones I remember best were yo-yos, hula hoops and roller skates. Maybe it was because I was shy, but it mattered very much that my present of desire was exactly ‘right’. A compendium of games was up market, but sets of draughts, snakes and ladders, Ludo or even tiddly-winks were not to be sniffed at. Later in the decade, board games like Monopoly and Cluedo came along, but they were expensive, so stockings were more likely to contain a pack of cards.

A compendium of games was up market, but sets of draughts, snakes and ladders, Ludo or even tiddly-winks were not to be sniffed at. Later in the decade, board games like Monopoly and Cluedo came along, but they were expensive, so stockings were more likely to contain a pack of cards. I invariably got one of the things specified on that list (or lists) I sent up the chimney. My parents would have been astounded to learn I felt the best bit of Christmas morning was opening my stocking. I loved those catch penny items such as chalks, crayons, puzzles, books and chocolate money, sold as stocking fillers.

I invariably got one of the things specified on that list (or lists) I sent up the chimney. My parents would have been astounded to learn I felt the best bit of Christmas morning was opening my stocking. I loved those catch penny items such as chalks, crayons, puzzles, books and chocolate money, sold as stocking fillers. British advertising’s greatest leap forward came in 1956 with the inception of ITV. Not having the ‘technology’ to receive Granada at first, my sister and I were late joining the advert junkies.

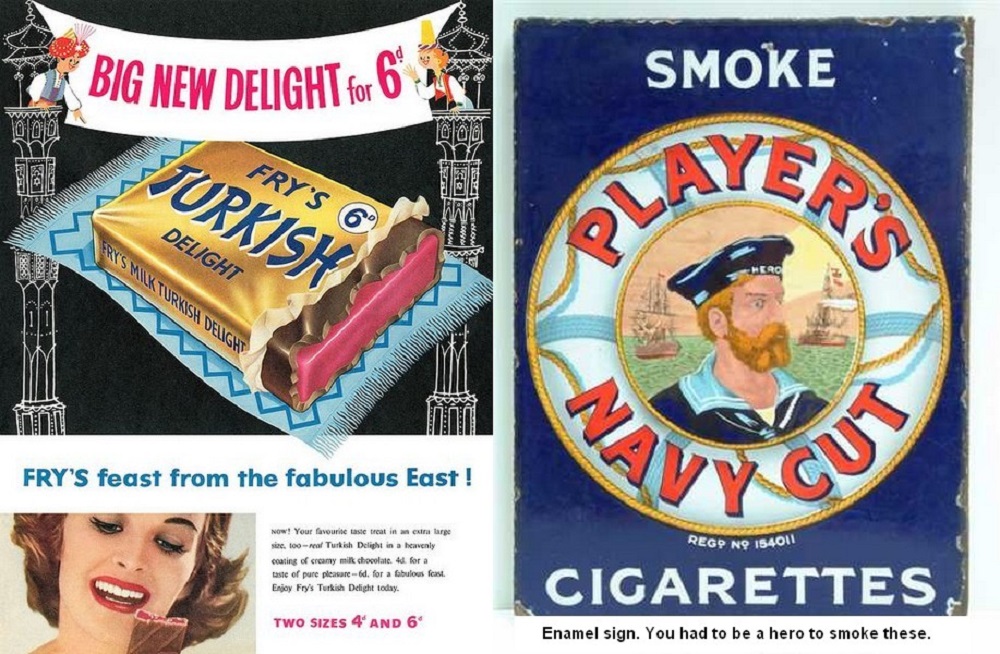

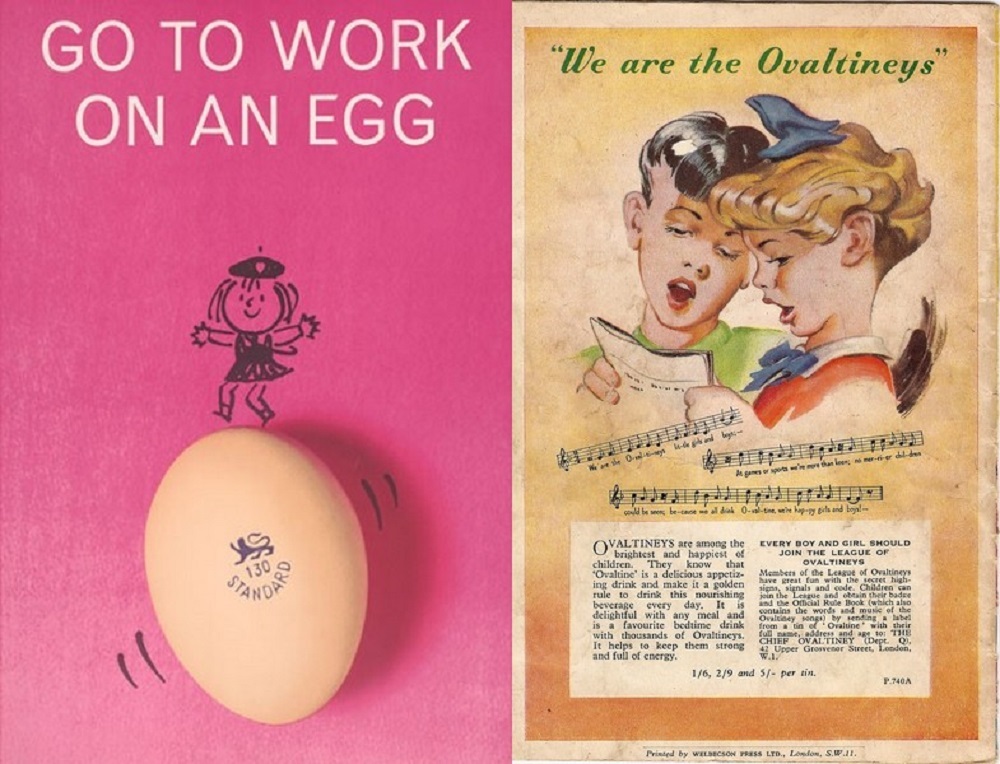

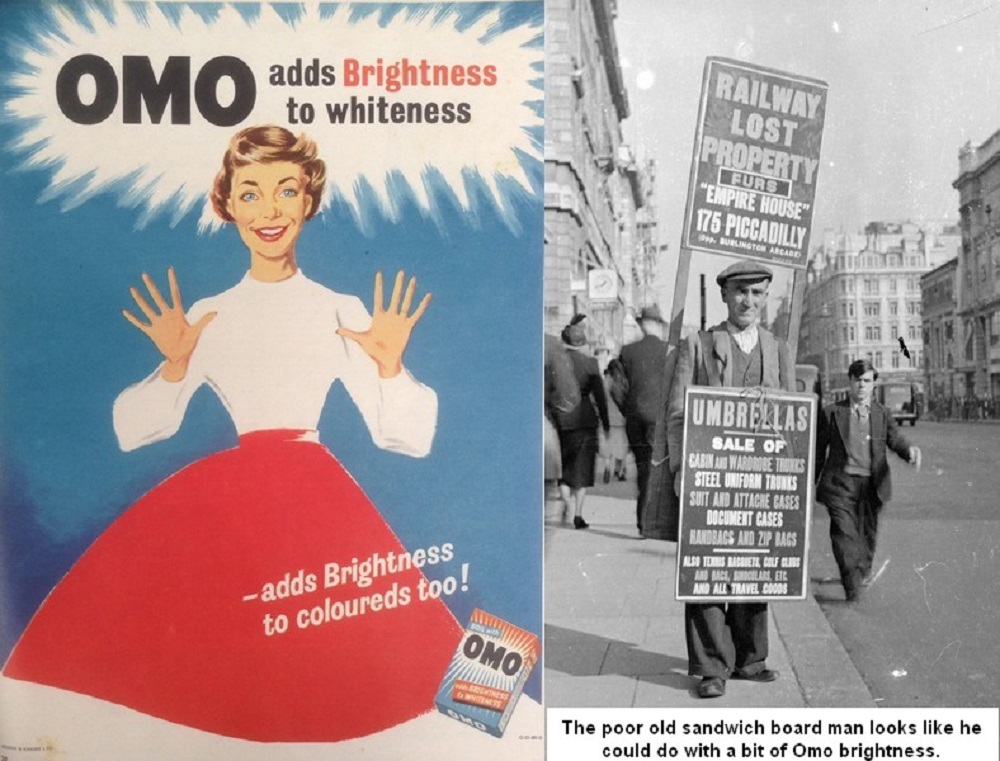

British advertising’s greatest leap forward came in 1956 with the inception of ITV. Not having the ‘technology’ to receive Granada at first, my sister and I were late joining the advert junkies. You could learn a lot from adverts. For instance, how to fortify the over forties, and that Turkish Delight is full of eastern promise. Before commercials, who knew Murray mints were the ‘too good to hurry mints’, or that everyone ought to ‘go to work on an egg’.

You could learn a lot from adverts. For instance, how to fortify the over forties, and that Turkish Delight is full of eastern promise. Before commercials, who knew Murray mints were the ‘too good to hurry mints’, or that everyone ought to ‘go to work on an egg’. The early 20th century circulation wars between newspapers were responsible for an idea that agencies pinched in the fifties. The free gift phenomenon produced such promotions as Daz roses. Strange as it sounds, those free gifts were an unintentional perk of my father’s job as manager of a GPO canteen. Manufacturers invariably included the equivalent quantity of the current free gift with bulk orders. Initially, the canteen ladies and our neighbours welcomed the unlikely coloured, plastic roses, but soon it became impossible to give the damn things away.

The early 20th century circulation wars between newspapers were responsible for an idea that agencies pinched in the fifties. The free gift phenomenon produced such promotions as Daz roses. Strange as it sounds, those free gifts were an unintentional perk of my father’s job as manager of a GPO canteen. Manufacturers invariably included the equivalent quantity of the current free gift with bulk orders. Initially, the canteen ladies and our neighbours welcomed the unlikely coloured, plastic roses, but soon it became impossible to give the damn things away. The trend toward pre-packaged goods was used as an advertising opportunity by manufacturers. The backs of packets soon featured prize winning competitions where the ‘decider’ was a slogan. It didn’t matter that the winner failed to set the advertising world alight, because dedicated sloganeers had already bought the product in order to enter.

The trend toward pre-packaged goods was used as an advertising opportunity by manufacturers. The backs of packets soon featured prize winning competitions where the ‘decider’ was a slogan. It didn’t matter that the winner failed to set the advertising world alight, because dedicated sloganeers had already bought the product in order to enter. Then there were the ‘send away for’ offers. My husband has never got over the half crown (twelve and a half pence) he paid out for one that took six months to arrive. The correctly addressed package containing the, elastic powered, swamp buggy, had toured two continents before reaching Blackpool, only to break almost immediately.

Then there were the ‘send away for’ offers. My husband has never got over the half crown (twelve and a half pence) he paid out for one that took six months to arrive. The correctly addressed package containing the, elastic powered, swamp buggy, had toured two continents before reaching Blackpool, only to break almost immediately. Travelling by train, my sister and I always looked out for a clever amalgamation of shop sign and billboard. It was a couple of workmen (up to twice life size) carrying a plank advertising Hall’s distemper (paint), as they apparently strolled across a field.

Travelling by train, my sister and I always looked out for a clever amalgamation of shop sign and billboard. It was a couple of workmen (up to twice life size) carrying a plank advertising Hall’s distemper (paint), as they apparently strolled across a field.