The fifties was the era when advertising came to cinemas and right into our living rooms, with the sole purpose of charming money from our pockets.

From 1953, Pearl and Dean became synonymous with picture going. The novelty of seeing familiar names from our local high streets, superimposed on stylish footage, entranced unsophisticated audiences.

At home, commercials were the price we had to pay for the popular music not available on BBC. Radio Luxembourg broadcast on medium wave where reception was patchy. But somehow, the Ovaltiney’s and Horace Bachelor with his ‘Pools’ Infra-draw method, managed to penetrate the static when the music couldn’t. British advertising’s greatest leap forward came in 1956 with the inception of ITV. Not having the ‘technology’ to receive Granada at first, my sister and I were late joining the advert junkies.

British advertising’s greatest leap forward came in 1956 with the inception of ITV. Not having the ‘technology’ to receive Granada at first, my sister and I were late joining the advert junkies.

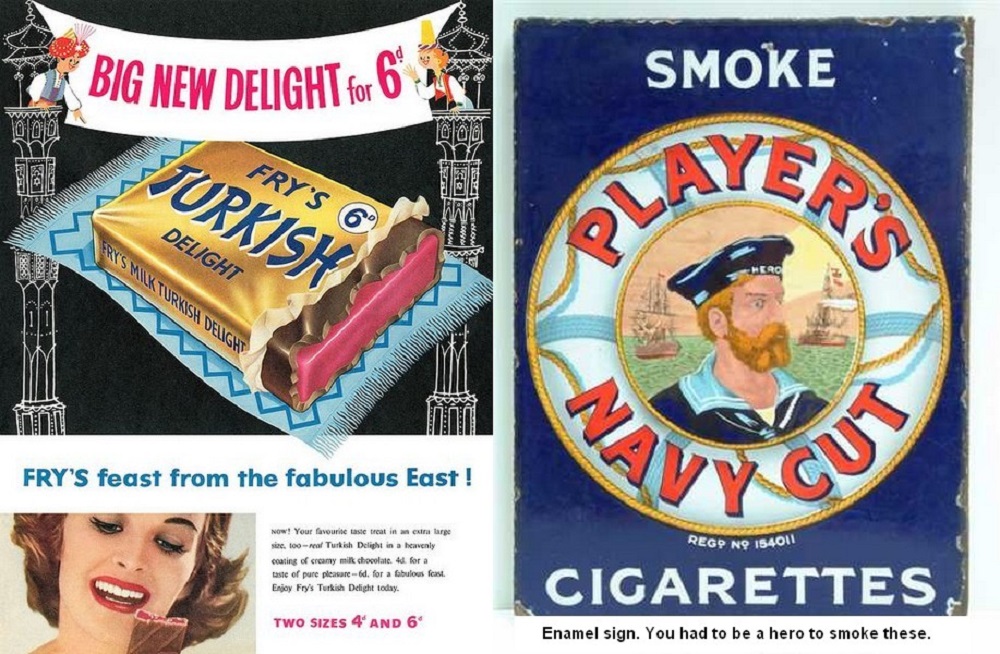

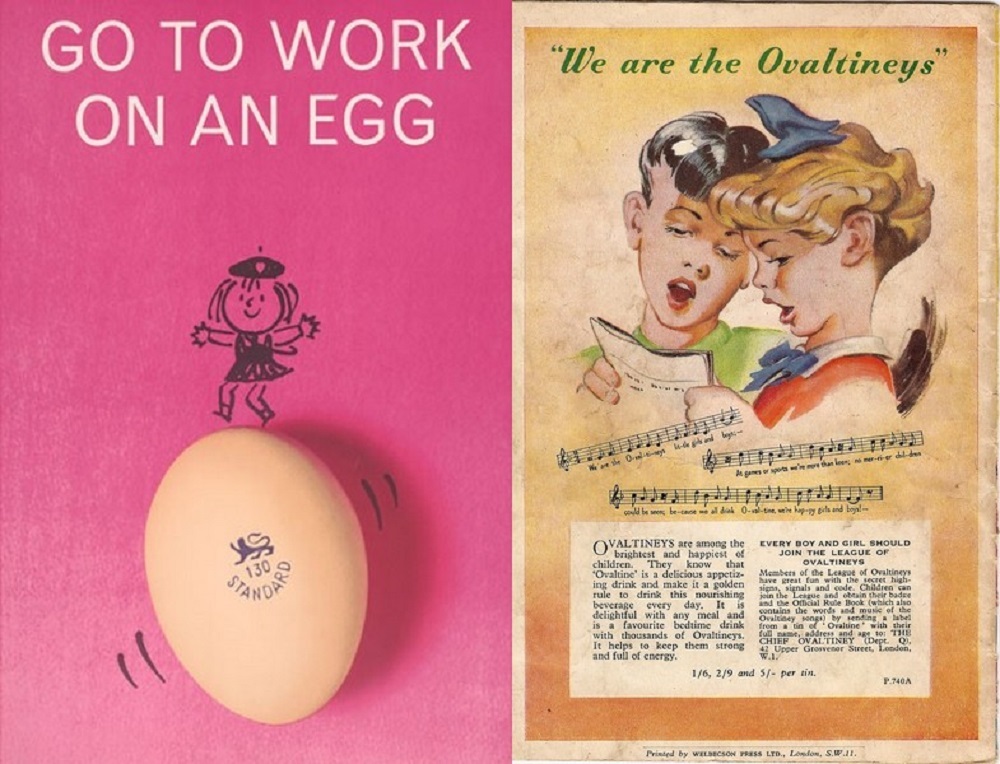

Until the novelty wore off, we begged to be allowed to stay up for the next commercial break. Our family didn’t use Pepsodent toothpaste, nor did we have a car, but we happily sang along with the jingles ‘you’ll wonder where the yellow went’ and the ‘Esso sign means happy motoring’. You could learn a lot from adverts. For instance, how to fortify the over forties, and that Turkish Delight is full of eastern promise. Before commercials, who knew Murray mints were the ‘too good to hurry mints’, or that everyone ought to ‘go to work on an egg’.

You could learn a lot from adverts. For instance, how to fortify the over forties, and that Turkish Delight is full of eastern promise. Before commercials, who knew Murray mints were the ‘too good to hurry mints’, or that everyone ought to ‘go to work on an egg’. The early 20th century circulation wars between newspapers were responsible for an idea that agencies pinched in the fifties. The free gift phenomenon produced such promotions as Daz roses. Strange as it sounds, those free gifts were an unintentional perk of my father’s job as manager of a GPO canteen. Manufacturers invariably included the equivalent quantity of the current free gift with bulk orders. Initially, the canteen ladies and our neighbours welcomed the unlikely coloured, plastic roses, but soon it became impossible to give the damn things away.

The early 20th century circulation wars between newspapers were responsible for an idea that agencies pinched in the fifties. The free gift phenomenon produced such promotions as Daz roses. Strange as it sounds, those free gifts were an unintentional perk of my father’s job as manager of a GPO canteen. Manufacturers invariably included the equivalent quantity of the current free gift with bulk orders. Initially, the canteen ladies and our neighbours welcomed the unlikely coloured, plastic roses, but soon it became impossible to give the damn things away.

My favourite free gift was a metal waste paper bin adorned with ‘cave paintings‘. For over 60 years, I kept one as a souvenir from the dozens dad brought home.

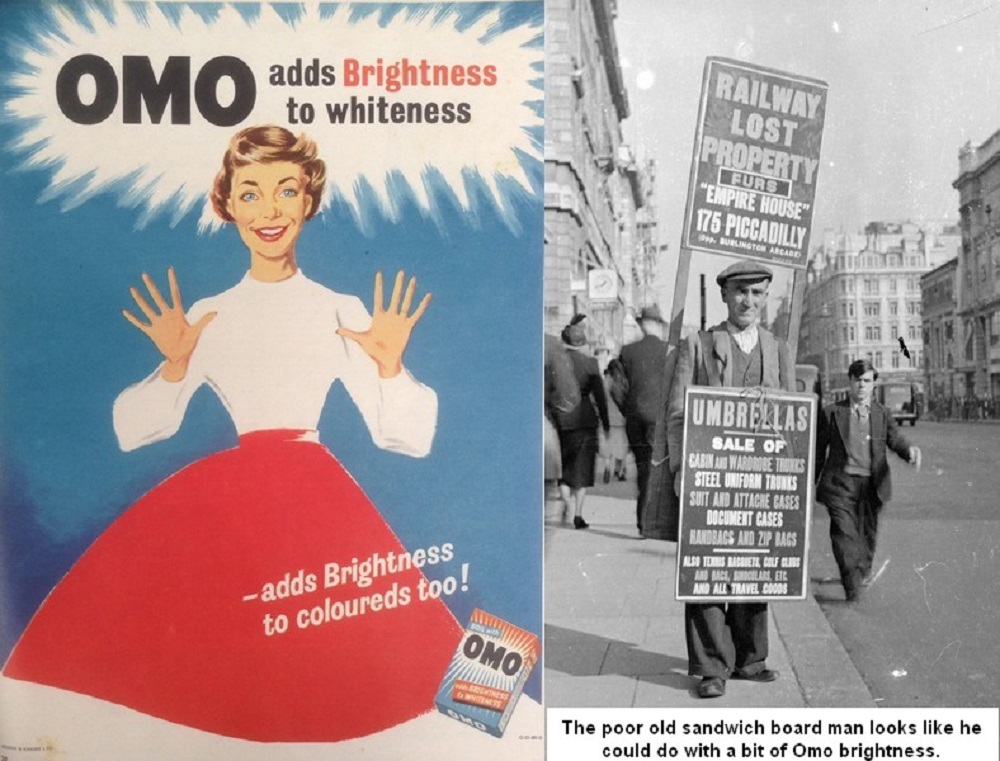

The nation’s letter boxes became the battle ground in the fifties Soap powder wars. It seemed that every day a ‘2d off’ coupon for Surf, Omo or Fairy Snow landed on the door mat. Sometimes you would come home to find a sample sized detergent packet, plus ‘money off next purchase coupon’, left on the door step. The trend toward pre-packaged goods was used as an advertising opportunity by manufacturers. The backs of packets soon featured prize winning competitions where the ‘decider’ was a slogan. It didn’t matter that the winner failed to set the advertising world alight, because dedicated sloganeers had already bought the product in order to enter.

The trend toward pre-packaged goods was used as an advertising opportunity by manufacturers. The backs of packets soon featured prize winning competitions where the ‘decider’ was a slogan. It didn’t matter that the winner failed to set the advertising world alight, because dedicated sloganeers had already bought the product in order to enter.

Breakfast cereals exploited the pester power of kids by incorporating cut-out models in the packaging. Later, collecting plastic figures from cereal packets became a national obsession. A plastic nuclear submarine which ran on baking powder was one of the most popular Kelloggs ‘giveaways’. Then there were the ‘send away for’ offers. My husband has never got over the half crown (twelve and a half pence) he paid out for one that took six months to arrive. The correctly addressed package containing the, elastic powered, swamp buggy, had toured two continents before reaching Blackpool, only to break almost immediately.

Then there were the ‘send away for’ offers. My husband has never got over the half crown (twelve and a half pence) he paid out for one that took six months to arrive. The correctly addressed package containing the, elastic powered, swamp buggy, had toured two continents before reaching Blackpool, only to break almost immediately.

Packet token collecting was not confined to kids. Many a Black and Greens (the family tea) packet top was exchanged for china tea sets or similar. When the cost of a postal order with its ‘poundage’ charge, plus p&p, was taken into account, the items would probably cost less from a department store.

In the great outdoors, colour changing electric signs, flashing out their advertising message, had returned after six years of blackout. And sometimes we were lucky enough to spot an aeroplane trailing a banner across the skies. Men down on their luck had the opportunity of earning a few shillings by walking the streets carrying ‘sandwich boards’ bearing adverts.

Advertising hoardings varying in size from the enormous to small newsagents’ boards, were a common sight around the streets. A welcome splash of colour in the drabness was provided by the enamelled tin shop signs, put there to attract customers and maintain brand awareness. Travelling by train, my sister and I always looked out for a clever amalgamation of shop sign and billboard. It was a couple of workmen (up to twice life size) carrying a plank advertising Hall’s distemper (paint), as they apparently strolled across a field.

Travelling by train, my sister and I always looked out for a clever amalgamation of shop sign and billboard. It was a couple of workmen (up to twice life size) carrying a plank advertising Hall’s distemper (paint), as they apparently strolled across a field.

Speaking personally, today’s adverts don’t have the charm of the ones featuring Joe, ‘the Esso Blee dooler’, or the Hoover which ‘beats as it sweeps, as it cleans’.

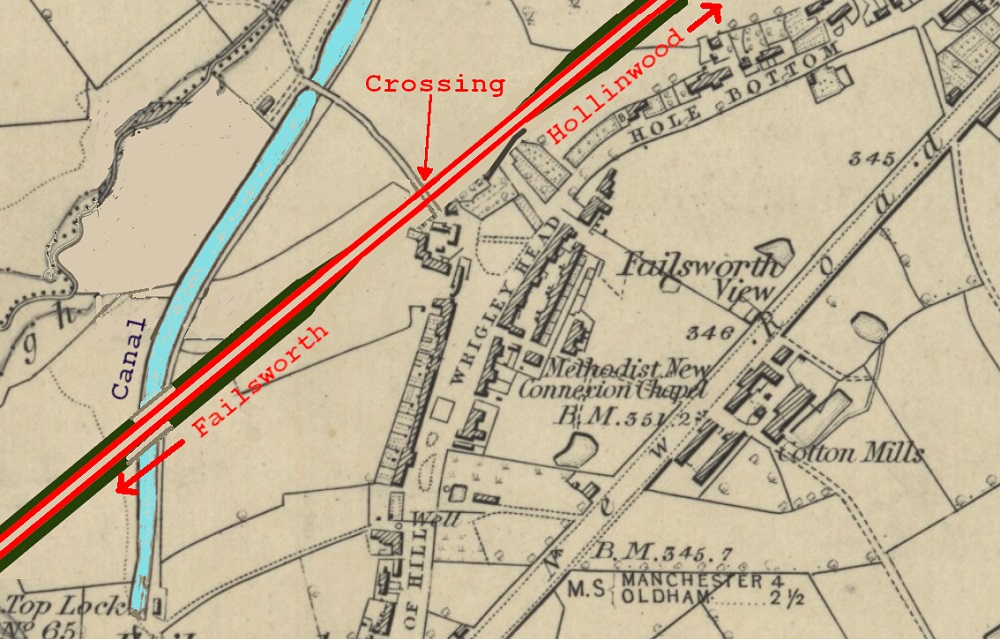

In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten…

In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten… At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system.

At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system. An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later.

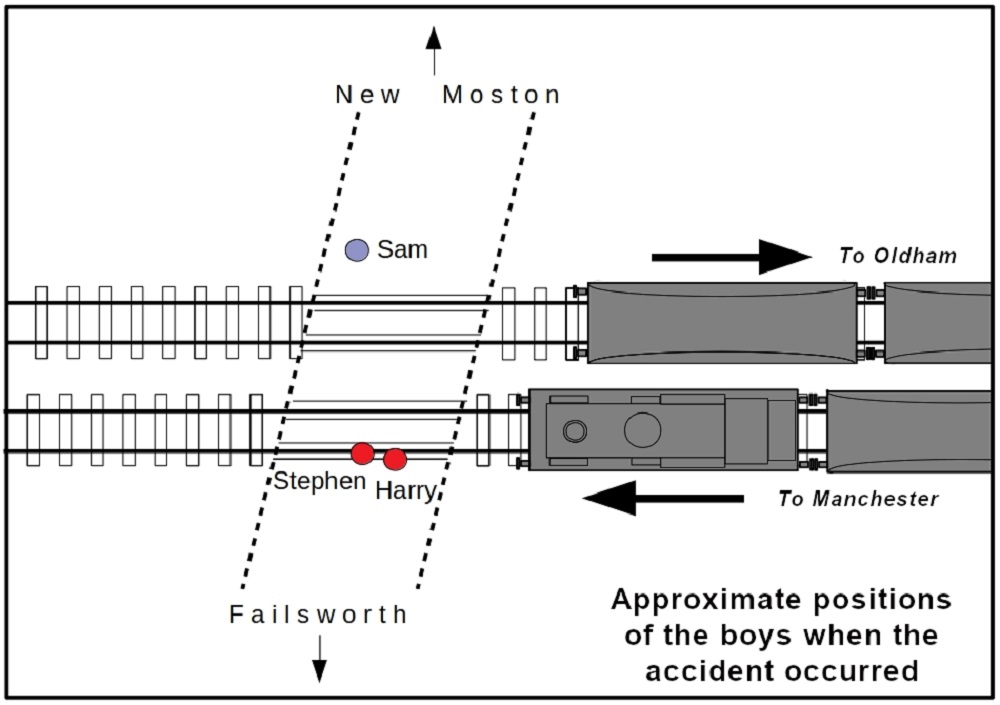

An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later. Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed.

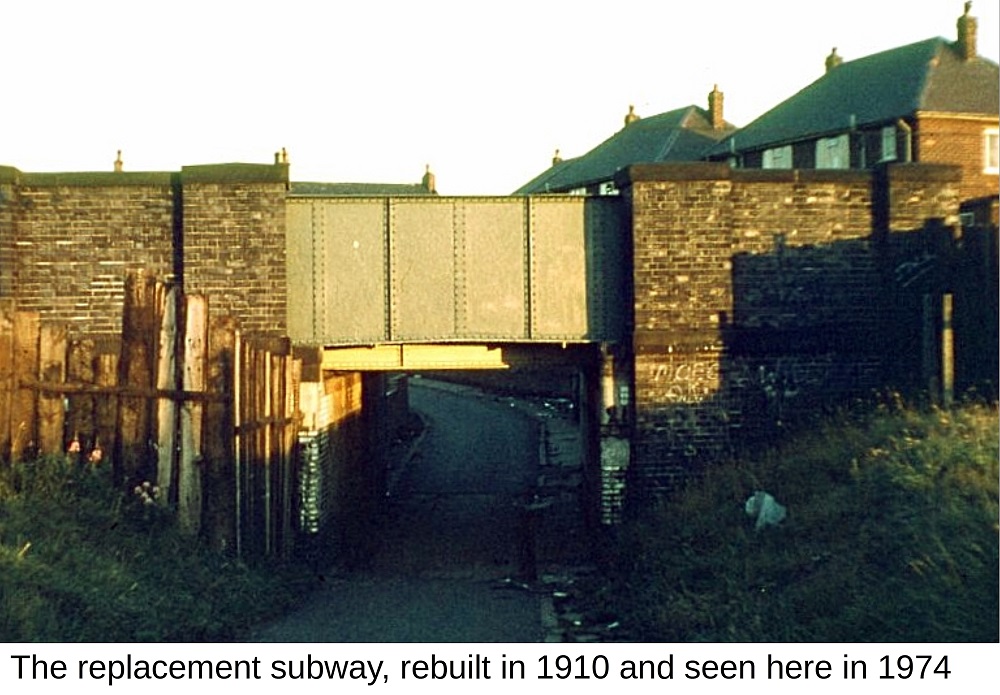

Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed. After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history.

After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history. Until mass vaccination all but eradicated whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever, their spectres remained ever present, especially in poorer areas.

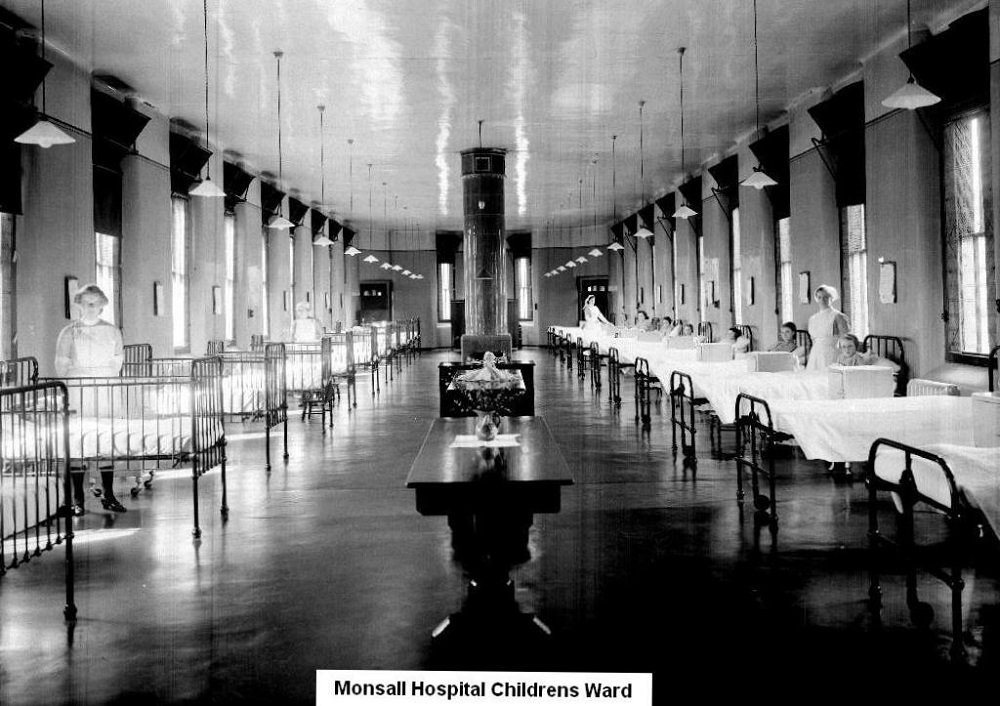

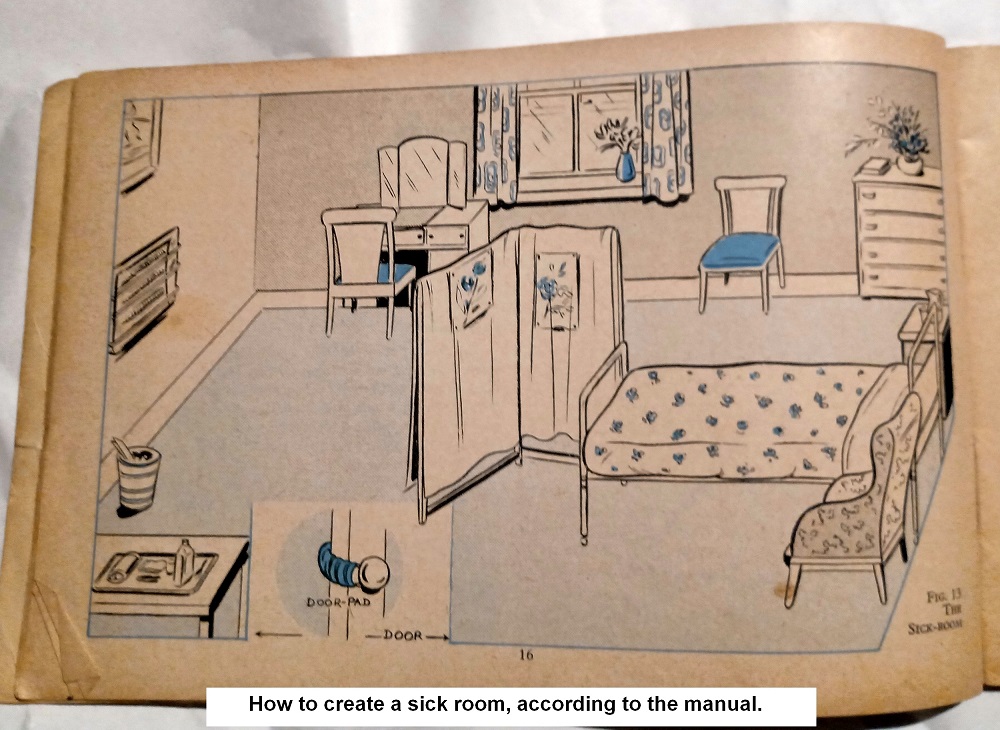

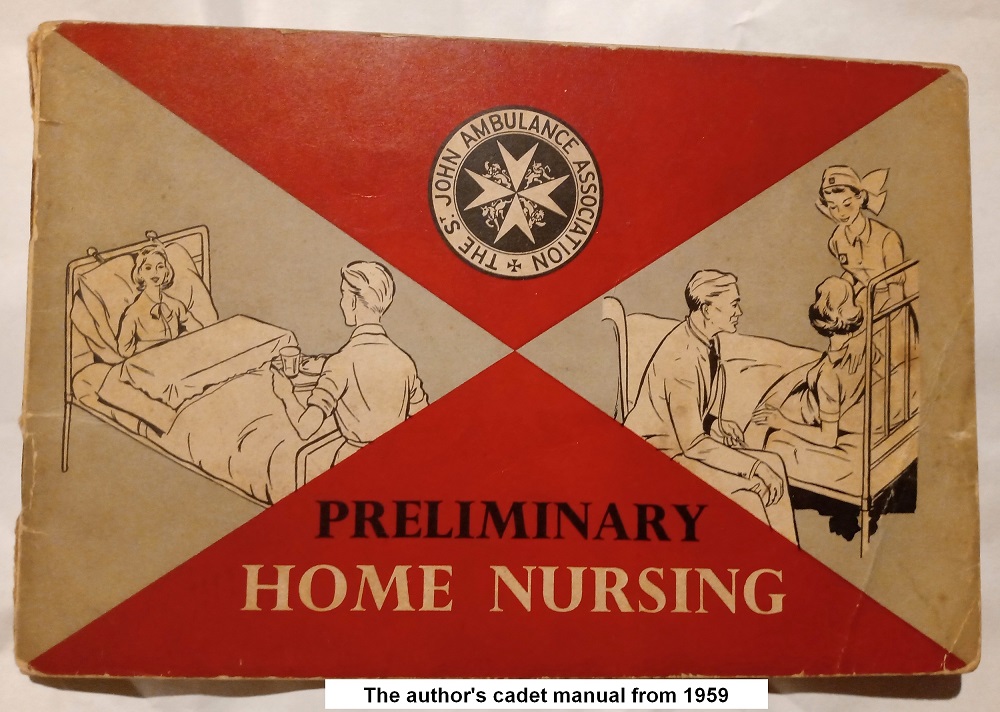

Until mass vaccination all but eradicated whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever, their spectres remained ever present, especially in poorer areas. In the fifties, the belief was that, sooner or later, every child would contract mumps, chicken pox and measles. To get it over with quickly, we were sent to play at the homes of contagious friends.

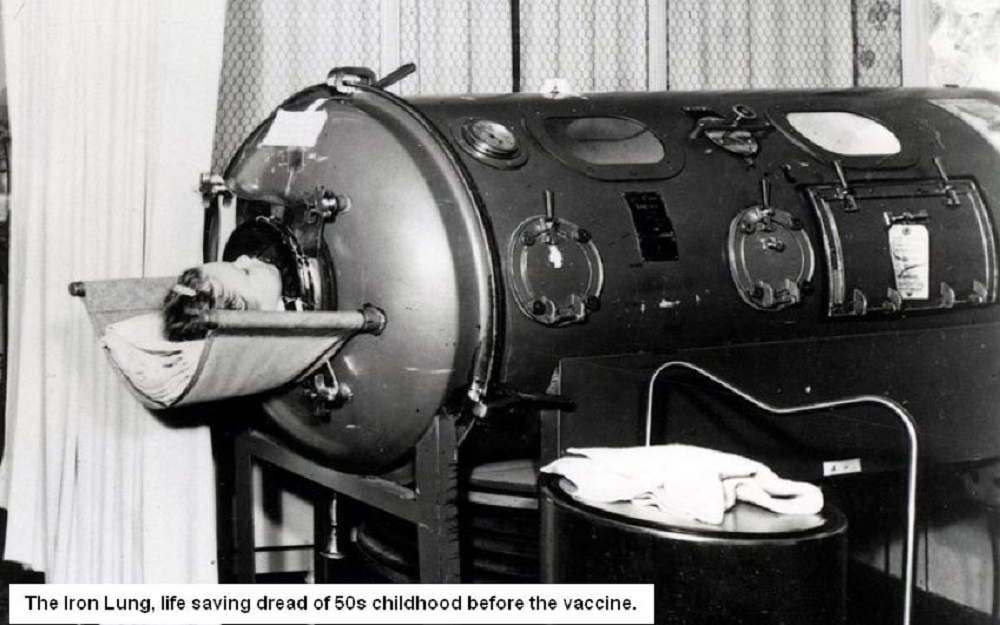

In the fifties, the belief was that, sooner or later, every child would contract mumps, chicken pox and measles. To get it over with quickly, we were sent to play at the homes of contagious friends. Throughout my childhood, TB and polio were the demon diseases. When I was about 9, there was a polio scare. Banner headlines exhorted parents not to allow children near open water. The previous afternoon, my friend Anne and I had been up to our welly tops in the Moston Brook, trying to build a dam. We kept the escapade from our parents, but visions of ‘iron lungs’ and metal leg callipers haunted our thoughts.

Throughout my childhood, TB and polio were the demon diseases. When I was about 9, there was a polio scare. Banner headlines exhorted parents not to allow children near open water. The previous afternoon, my friend Anne and I had been up to our welly tops in the Moston Brook, trying to build a dam. We kept the escapade from our parents, but visions of ‘iron lungs’ and metal leg callipers haunted our thoughts. Later, a polio vaccine became available. Subsequently it would be administered as syrup or on a sugar lump, but for us it was the dreaded ‘prick’, as injections were then commonly known.

Later, a polio vaccine became available. Subsequently it would be administered as syrup or on a sugar lump, but for us it was the dreaded ‘prick’, as injections were then commonly known. Eventually my tonsils burst, and had to be removed at Booth Hall. Two days in hospital was followed by a fortnight off school to convalesce.

Eventually my tonsils burst, and had to be removed at Booth Hall. Two days in hospital was followed by a fortnight off school to convalesce. Although complaints from the past seem to be re-surfacing, I don’t hear anyone mentioning chilblains these days. Girls at my school were repeatedly warned not to stand against the cloakroom radiators as it would only increase the agony. And as yet, I haven’t spotted a ring worm sufferer with a shaven head adorned with Gentian Violet. And when did they stop painting it on throats?

Although complaints from the past seem to be re-surfacing, I don’t hear anyone mentioning chilblains these days. Girls at my school were repeatedly warned not to stand against the cloakroom radiators as it would only increase the agony. And as yet, I haven’t spotted a ring worm sufferer with a shaven head adorned with Gentian Violet. And when did they stop painting it on throats?