St. Mary’s Road, Moston, is almost entirely residential nowadays, but not so long ago it housed several industries, including one which is almost completely forgotten.

John Johnson of Manchester, an iron wire-drawer and maker of nails and pins, had a business in the early 1800s on Shudehill, and later in Ancoats and Dale St. In 1838, he handed over the business to his younger sons, Richard and William (born in 1809 and 1811), the firm being named “Richard Johnson and Brother”. An older son, Thomas Fildes Johnson, became a cotton spinner, taking no part in the wire trade, but Richard and William expanded the business and made their reputation by supplying the wires for the first cross-Channel telegraph cable in 1851.

In 1853 the brothers took over the Bradford (Manchester) ironworks on Forge Lane and after William’s death in 1860, Thomas’s son John Thewlis Johnson became a partner, the firm now becoming “Richard Johnson and Nephew”. This is a name still familiar to many, as it thrived right up to the 1970s, when it was acquired by Firth Brown Ltd. The brothers also held shares in the nearby Bradford Colliery.

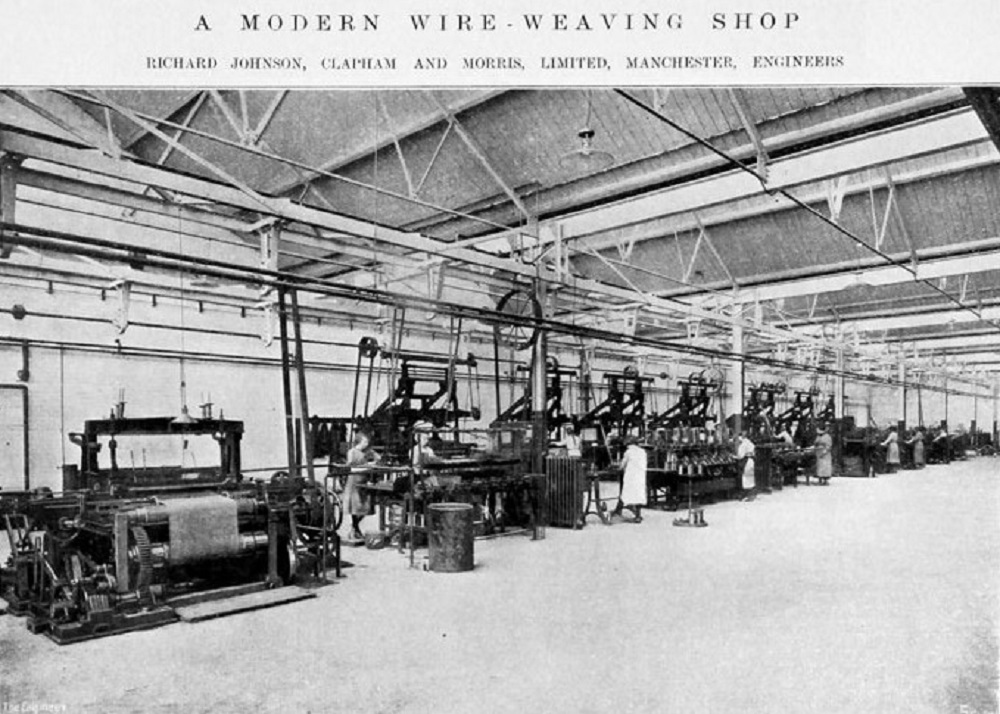

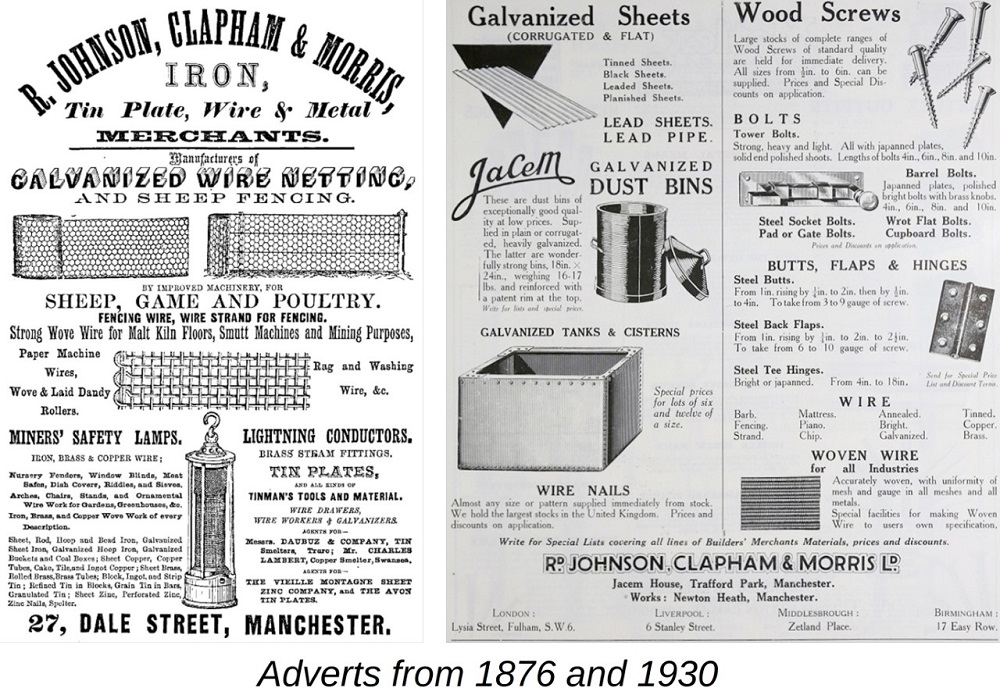

In addition to producing wire and cables, which now included copper and brass as well as iron, around 1860 Richard co-founded another firm to make hardware items such as wire gauze, netting, brick ties, concrete reinforcing mesh and many other items for domestic as well as industrial use. Two new partners joined him in this venture: William Clapham and Joseph Morris (from Swansea) – this firm, based at the old Dale St premises, was named Johnson, Clapham and Morris. The combined operations employed around 550 people in 1861.

The company enjoyed continued success and after St.Clement’s church on Lever St closed in 1878, it was acquired for their main office and warehouse. By 1880, Richard had earned enough to buy a grand house in Chislehurst, Kent, where he died in Feb 1881, although his body was brought back to Cheetham Hill Wesleyan Cemetery for burial in the family vault. An only son, also Richard, had died in 1865, so once again it was a nephew, William Henry, that carried on the Johnson name.

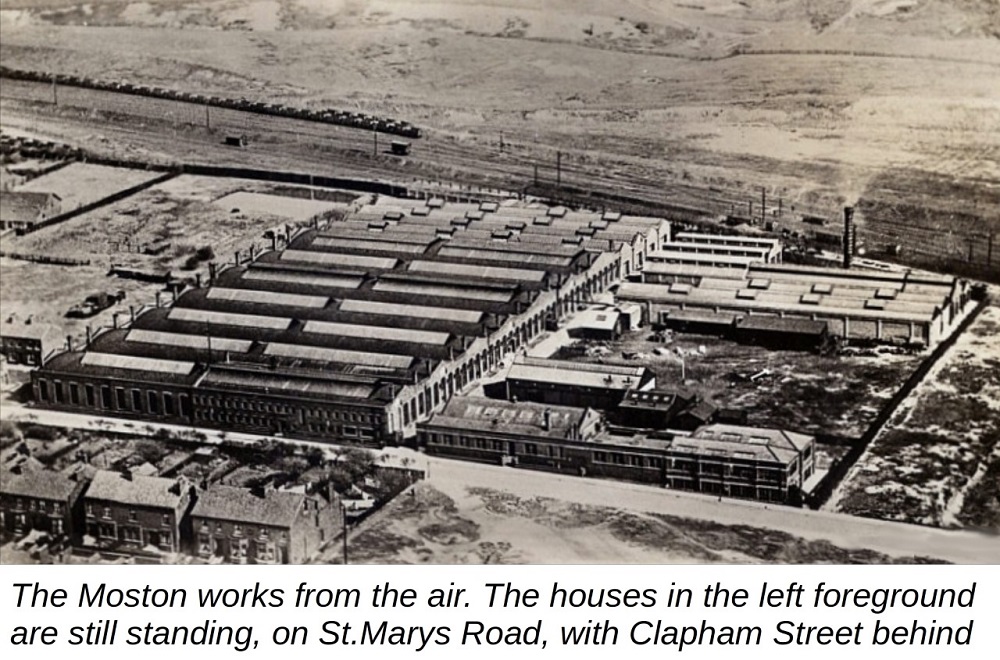

Phenomenal business expansion prompted the establishment of a new, larger works in Moston, (sometimes referred to as Newton Heath), begun in 1902 off St.Mary’s Road, close to Tymm St. The new – appropriately named – Clapham St and Wireworks St (now Beechdale Close) were later added. Miner’s lamps, bedsteads, galvanised dustbins, lawn-mowers and all manner of other products supplemented their range, under the brand-name “Jacem”, formed from the initial letters of the company name.

William Henry Johnson had four sons, of whom two were killed in action in Belgium during the First World War. Since their father had died six months before the war started, each in turn briefly became managing director. William Morton Johnson was a Captain in the Manchester Regiment, and died on 2 July 1916; Capt. Ronald Lindsay Johnson, Royal Field Artillery, was killed on 29 May 1917. Ronald, in his will, desired his estate to be shared among the workers at J, C & M – this was later effected by purchasing part of the Broadhurst estate and creating playing fields for the works staff, named in his memory.

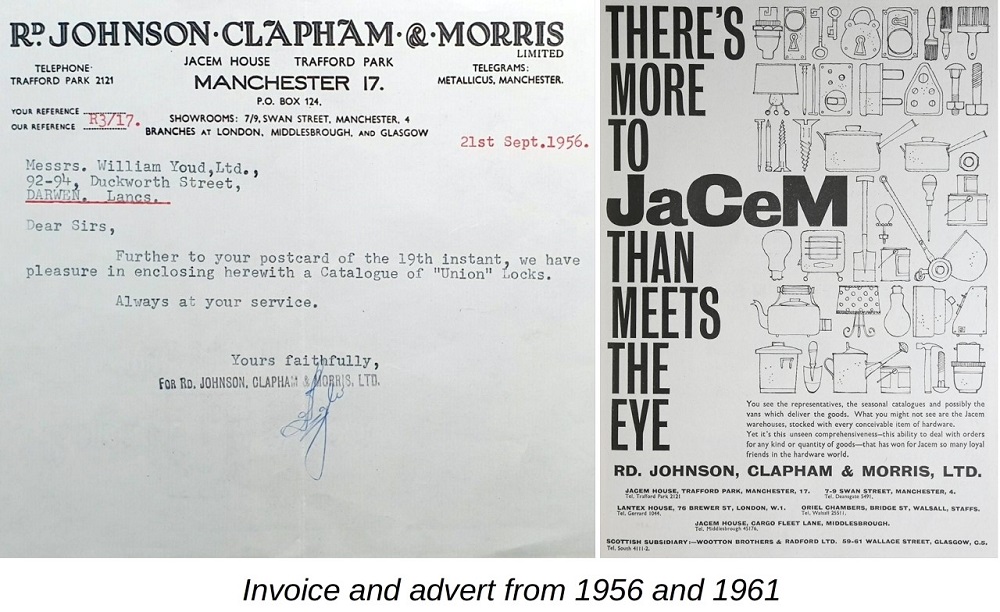

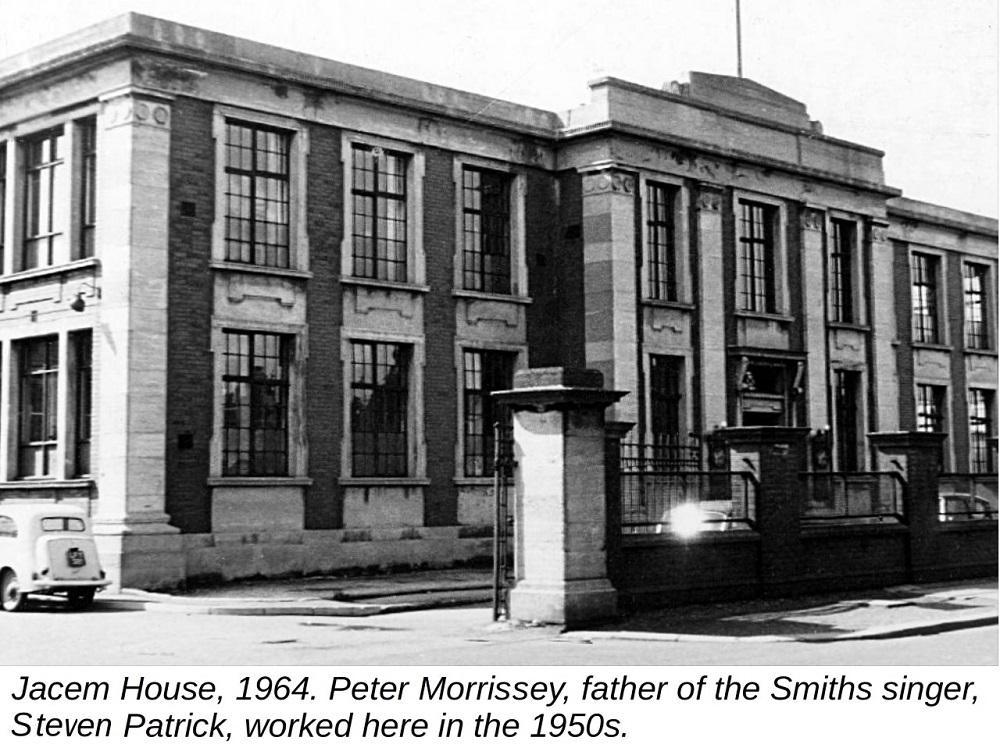

Around 1925, the company acquired premises next to St. Cuthbert’s church on Third Avenue, Trafford Park, which they named “Jacem House”. By now they were acting as general hardware wholesalers, and this became their head office and warehouse, while retaining the works in Moston and elsewhere for manufacturing their own-brand items. At their height, they also had premises in Liverpool, London, Middlesbrough and Glasgow, and offices in Australia and New Zealand.

As “Jacem”, they continued to supply hardware goods and were reputed to be a good firm to work for – they even featured in a promotional film for Stretford Borough in 1933, showing off their well-equipped staff canteen. Gradually, however, the manufacturing side was scaled down, and the Moston site was sold in 1934 to Ferranti Ltd (another story, as they say).

The company continued to trade as wholesalers up to the 1970s at least, and although I have not discovered exactly when it closed, Jacem House was demolished during 1989, much of Trafford Park ‘village’ following soon after.