We were not fortunate enough to have a television for the coronation, but we knew a family who did.

On the morning of the day itself, the wireless broadcast the news that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had ‘conquered’ Everest.

With my baby sister in her lemon matinee jacket, matching leggings and bonnet, mum, dad and I set off with the pram to walk through the flag- and bunting-bedecked streets towards Rochdale Road.

The friends of my parents who had the television kept a greengrocers shop. Not only was this my first experience of a television set, but also the first time I had been ‘behind the scenes’ of a shop.

It’s estimated that an average of 17 people watched each set on the day. That number certainly accords with my memory of the crowd of people squeezed into the shop’s little back parlour.

On the Queen’s insistence, cameras had been allowed into Westminster Abbey to film the ceremony. 200 microphones were set up in the Abbey and it’s said 3 million people lined the streets along the route. With all that build up, we were anticipating something very special.

We kids sat around on the floor for what seemed like an age while the set was ‘warming up’. The tiny screen showed people standing in the rain, or perhaps it was the ‘interference’ we later came to associate with Outside Broadcasts.

To fill the gaps when not much was happening, the plummy-voiced BBC commentators interviewed members of the public who thought it worth a night sleeping on the pavement to secure a good place for the procession. They also went on at great length about the headgear and robes of state we could expect the different ranks of nobility to be wearing.

It’s hardly surprising we youngsters (as well as some of the grown-ups) got a bit restive. Mary, the daughter of the house, was directed to ‘take us off somewhere’ to play. As it was raining outside, we ended up on the staircase, amusing ourselves as best we could, until mum announced it was time to get my sister home.

If it hadn’t been for the cinema newsreels, I might have gone through life with only the grainy grey images of a day which cost an estimated £157 million.

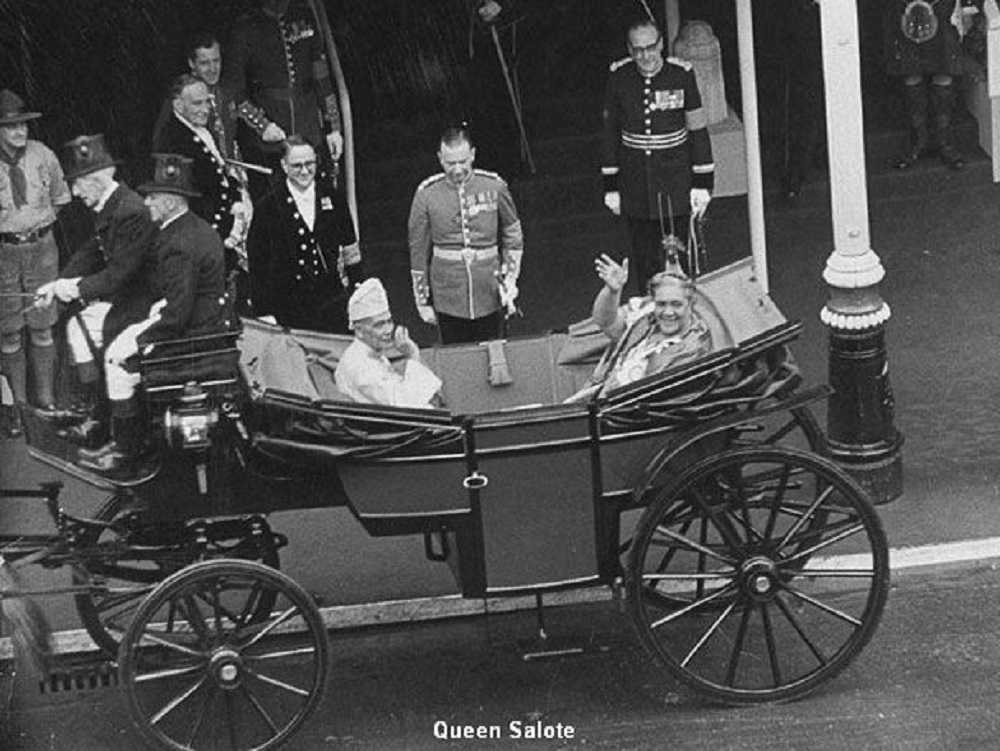

Of all the dignitaries attending the Abbey, it was Queen Salote of Tonga who stole the show. She rode in an open-topped carriage with the Sultan of Kelantan. The Queen was as large and imposing as the Sultan was diminutive. Someone asked “who is that man sitting opposite her?” – the answer (wrongly attributed to Noel Coward) came back as “her lunch”.

At the luncheon, what Queen Salote and the other guests were actually served was Coronation Chicken, a dish specially devised for the occasion.

More than 20 million viewers around the world were able to watch the coronation. With 750 commentators, broadcasting in 39 languages, it was truly an international spectacle.

RAF Canberras flew BBC film recordings across the Atlantic so CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company) could put it out on 2nd June. The Canadian servicemen, fighting in Korea, might have missed out on the coronation, but they had an improvised celebration by sending up red, white and blue flares.

Australia didn’t then have a full-time TV service, but a Qantas airliner flew film of the coronation to Australia in a record-breaking time of 53 hours 28 minutes.

In London there was a fireworks display on Victoria Embankment, but because of the inclement weather many street parties were either called off or moved to church halls.

I’m wondering if the elaborate Britannia costume my mother made me was intended for a fancy dress competition at a party that never happened? I can’t think of any reason for the time and expense that went into it otherwise.

In coronation year, the GPO issued special edition postage stamps to satisfy the philatelists. For the ordinary souvenir hunter, there were commemorative crown (5 shillings or 25p) coins and medals which are probably still knocking around in their thousands.

Of all the coronation memorabilia, the one thing best forgotten is Dickie Valentine’s recording of ‘In a Golden Coach, There’s a Heart of Gold’, which reached number 7 in the charts. Those lyrics probably stripped the nation’s teeth of more enamel than all the sweets consumed since rationing ceased in February of that year.