The story of the vast electrical empire begun by Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti, born in Liverpool in 1846, is complex, but many Mostonians remember the firm’s local connection. When the wireworks of Johnson, Clapham and Morris, off St. Mary’s Road, was put up for sale in 1934, Ferranti’s domestic wireless (radio) market was already booming, more so than the Wickentree Lane factory could cope with, and so the Moston site was purchased, refitted and enlarged considerably.

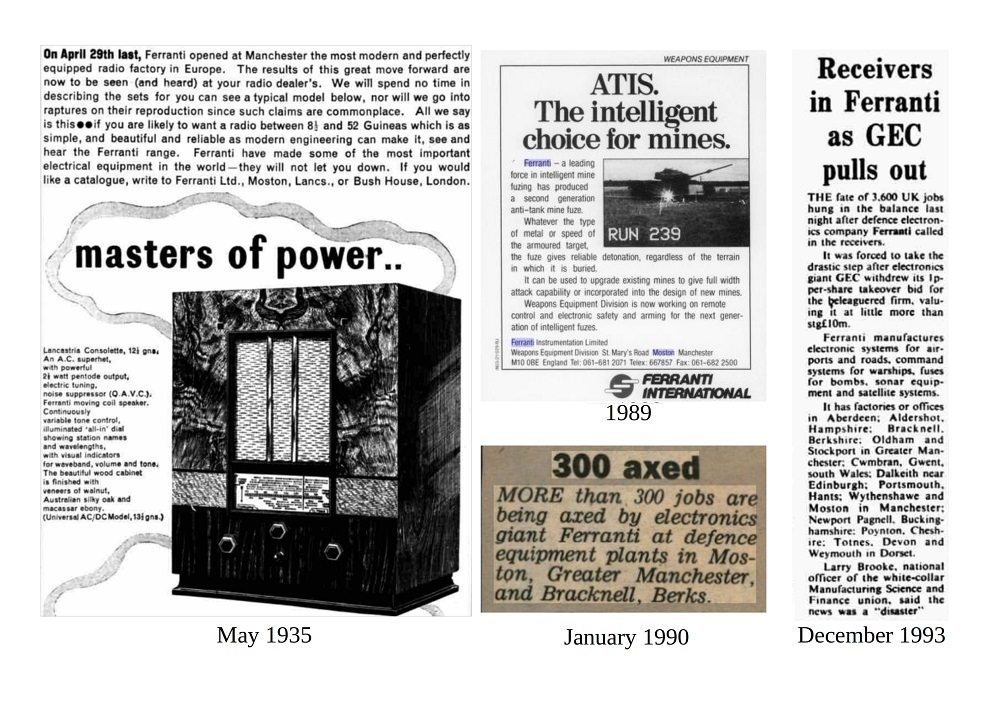

Said to be the best-equipped radio works in Europe, it opened on 29 April 1935 and initially employed around 1,000 people. Within 4 months the workforce had reached 3,000 and it was notable at the time that three quarters of the staff were women.

The wireless had become the essential news and entertainment console in most homes, and was considered a stylish item of furniture, to boot. Cabinet-making and glass-working skills were as much in demand as metalwork and electrical assembly. The range at Moston soon expanded to include meters and all kinds of domestic appliances: portable radios, gramophones, televisions, radiant fires, clocks and even electric irons.

Ferranti were also major producers of components for other manufacturers. When war was declared in 1939, the Moston site concentrated on instrument panels for aircraft and naval vessels, and were leaders in gyroscopic guidance systems, military radio systems and the development of radar. Other factories were opened to continue this work, in Edinburgh and elsewhere.

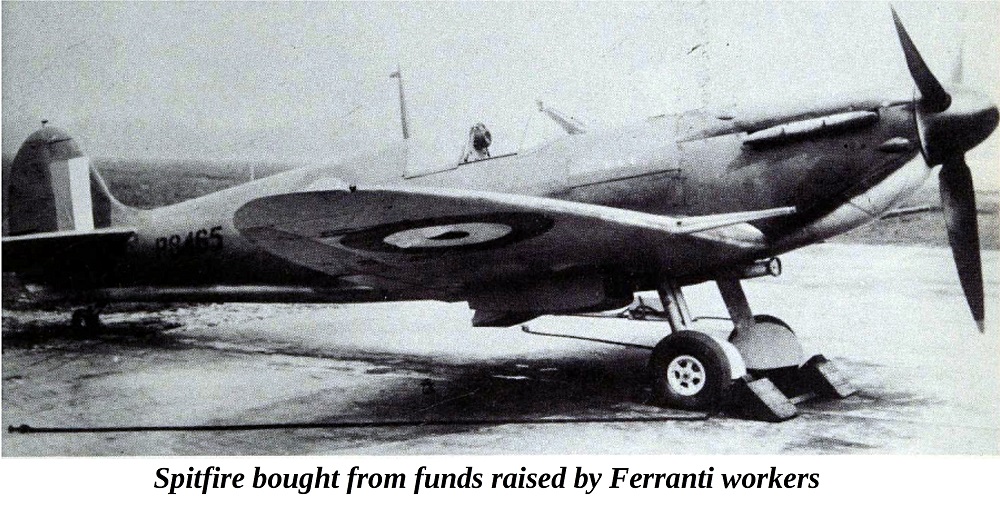

Although not directly involved in aircraft production, there was encouragement during the war for large firms to sponsor the building of aircraft, often supplemented by voluntary donations from the staff, and the St. Mary’s Road workforce ‘did their bit’. In 1940 they raised funds for the building of Spitfire P8465, which served with the RAF 303 (Polish) Squadron until shot down in 1941.

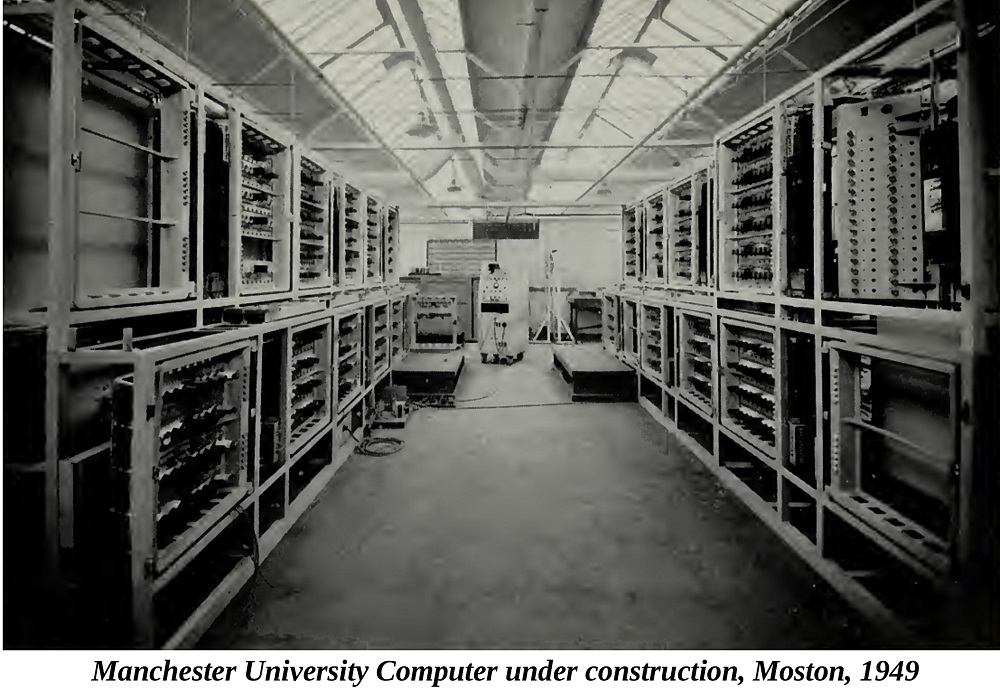

Not only in the air, Ferranti instruments were to be found on the bridges of Canadian and Royal Navy ships and many terrestrial defence systems. A spin-off from wartime research, particularly in the USA, was the development of the computer, an early use of which was in trajectory calculations for gun and missile aiming.

The essential quality of a computer, as opposed to a calculator, was that the same machine could be set up to do many different types of calculation, and that each set of instructions (program), and its results, could be displayed and stored electronically for future use. With the guidance of Dr. Alan Turing, a frequent visitor to Moston, a prototype computer was built by Ferranti for Manchester University in 1949.

Later refinements led to the Ferranti Mark I, the first reasonably successful commercial computer to be made in Britain – also at St. Mary’s Road. Although these early machines used valves in their logic circuits (and could easily fill a large bedroom!), Ferranti were in the vanguard in developing solid-state components such as transistors and, later, silicon devices and integrated circuits; much smaller, faster and cheaper than valves. Today, the average smartphone has far more computing power than the Mark I, but the essential operating logic is the same.

The Moston factory continued to diversify, particularly into telephones, automated switchboards and scientific instruments, and the Ferranti Group established several general divisions, such as the large transformer works opened in 1955 on Hollinwood Avenue. In 1958, the domestic appliance business was sold to the (then) well-known ‘Ekco’ brand (E.K.Cole Ltd) and the focus turned to military, commercial and industrial equipment.

By the 1960s, Ferranti was producing guidance systems and radar equipment for the Bloodhound missile, and had opened other plants at Wythenshawe and Cheadle Heath. From the 1980s they were making integrated circuits for (amongst others) the Acorn and BBC home computers, as well as their own ‘Advance’ range of IBM-compatible machines.

Defence work, telecommunications, instrumentation and component manufacture were all money-spinners, and at their height Ferranti owned twenty-two sites in England, Scotland, Wales and other countries. The Moston site was enlarged several times and as recently as 1986 was extending its training centre at Moston. Then – it all went wrong!

Ferranti made a disastrous investment in USA-based International Signal & Control, whose valuation proved to be completely bogus; they were ultimately prosecuted in the U.S. for fraud. Ferranti inherited massive debts, their share value plummeted and redundancies began in 1990. A last-minute rescue plan by GEC failed and receivers were called in during December 1993. Asset-stripping followed, some divisions being sold off entire (continuing to trade under Ferranti and other names), other parts being acquired by Siemens, Plessey and others.

The Moston site had closed completely by December 1994 and over a few short years was erased from the landscape and replaced by housing. The vast empire was no more.