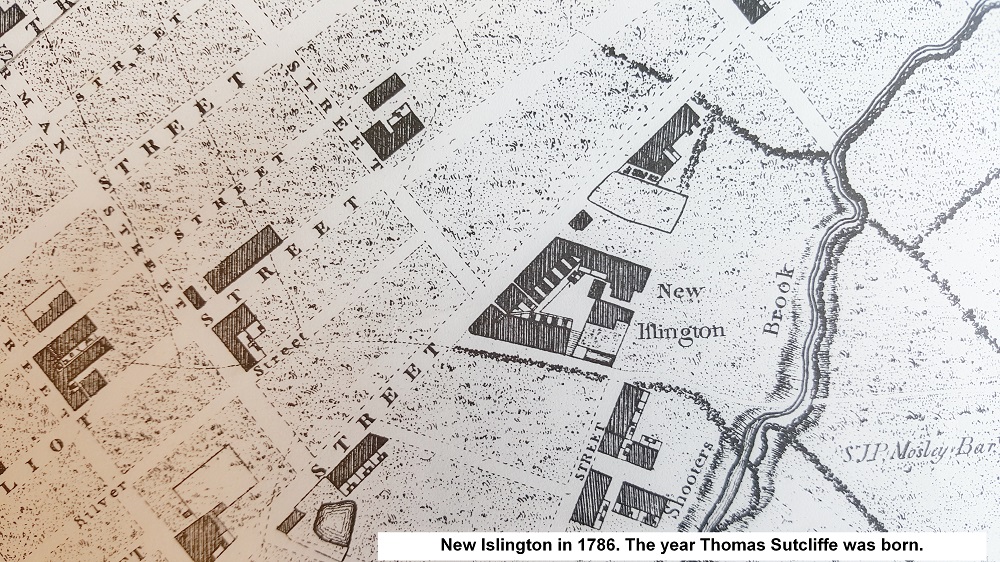

When I was immersed in researching Manchester’s worker’s houses (built 1750-1850) it suddenly occurred to me that these dwellings exactly paralleled my own family’s history. My 4 times great grandfather’s birth in 1786 coincided with the influx of country people seeking work in Manchester’s mills. The majority were casualties of mechanisation and newly introduced farming methods. Casual labour was replacing secure employment with a subsequent forfeiting of tied cottages.

My 4 times great grandfather’s birth in 1786 coincided with the influx of country people seeking work in Manchester’s mills. The majority were casualties of mechanisation and newly introduced farming methods. Casual labour was replacing secure employment with a subsequent forfeiting of tied cottages. Many families were reduced to sharing turf huts erected on waste or common land with their livestock. But at the whim of a land owner, the turf huts could be pulled down, and the occupants driven beyond the parish boundaries.

Many families were reduced to sharing turf huts erected on waste or common land with their livestock. But at the whim of a land owner, the turf huts could be pulled down, and the occupants driven beyond the parish boundaries.

As the destitute people surged into Manchester, the middle classes decided it was time to leave the central districts. New arrivals packed themselves into the vacated properties, as well as the two roomed dwellings of the labouring classes. Central districts soon reached bursting point, and speculative builders turned their attention to Ancoats and Collyhurst.

Central districts soon reached bursting point, and speculative builders turned their attention to Ancoats and Collyhurst.

Ancoats was the world’s first exclusively working class suburb. My ancestors were already there as it began to spread out from the angle formed by Oldham Road (then Newton Lane) and Great Ancoats Street.

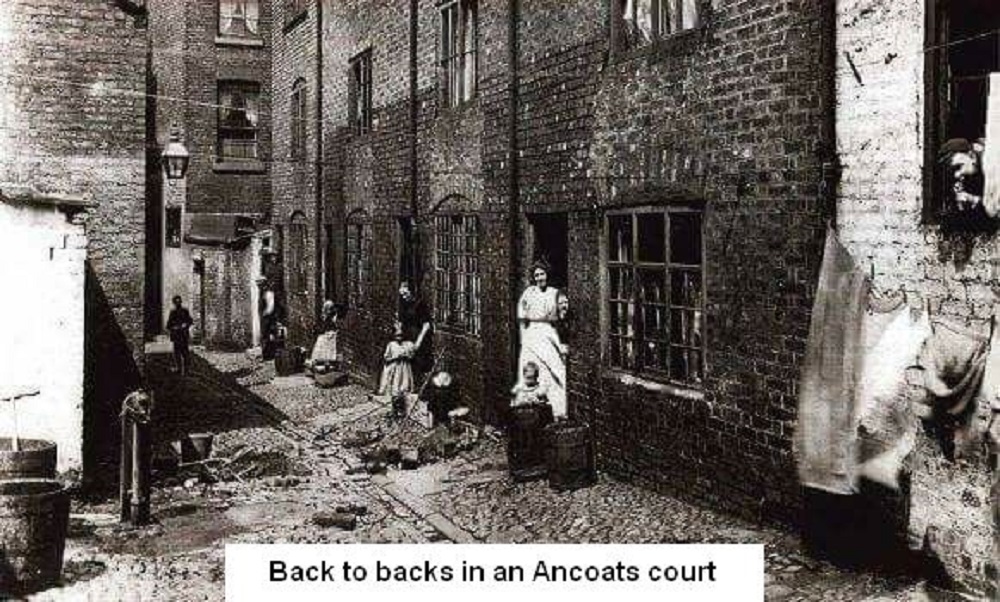

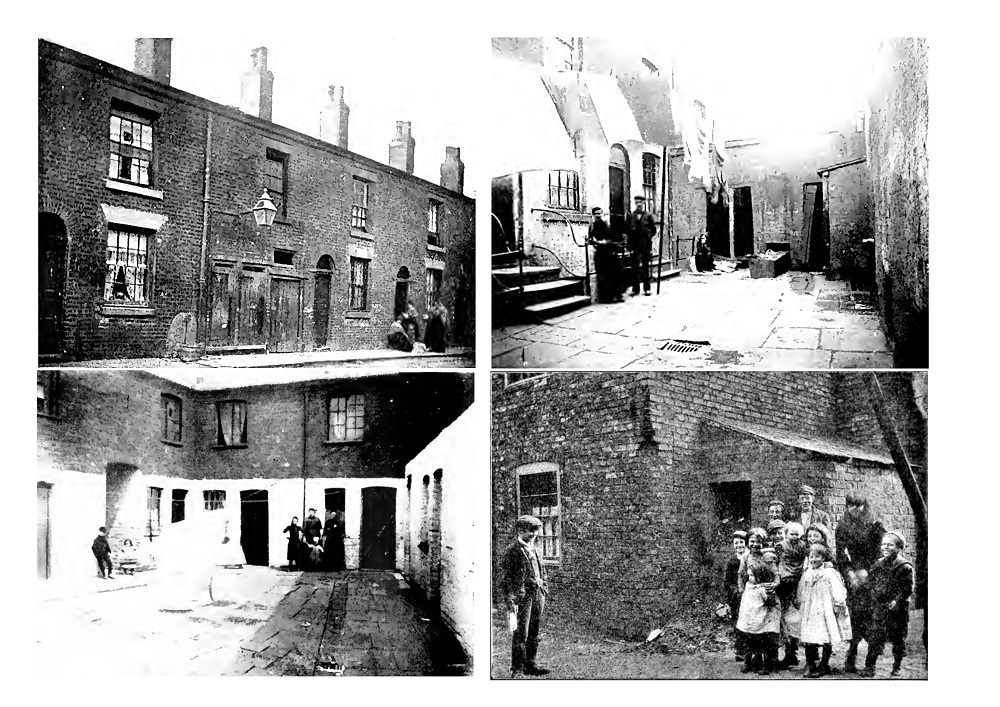

Today our picture of a typical working class house is generally a late Victorian terrace with a back entry. However, Cottonopolis was created by workers who spent their lives in two roomed dwellings built with single brick walls and only an open fire for cooking. Yards were communal, and contained cess pits or middens which it was nobody’s responsibility to empty. The intermittent water supply would have come from a pump or tap in the street. Primitive as these dwellings were, property owners soon realised that one up/one down terraces would yield more profit if they were constructed back-to-back (sharing a central wall).

Primitive as these dwellings were, property owners soon realised that one up/one down terraces would yield more profit if they were constructed back-to-back (sharing a central wall).

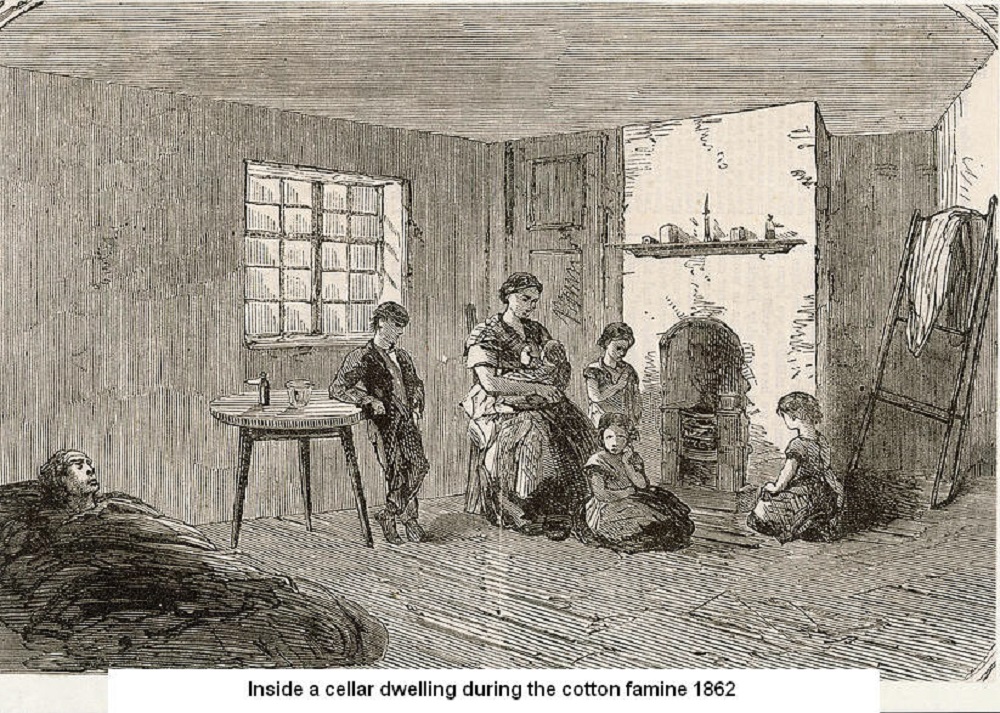

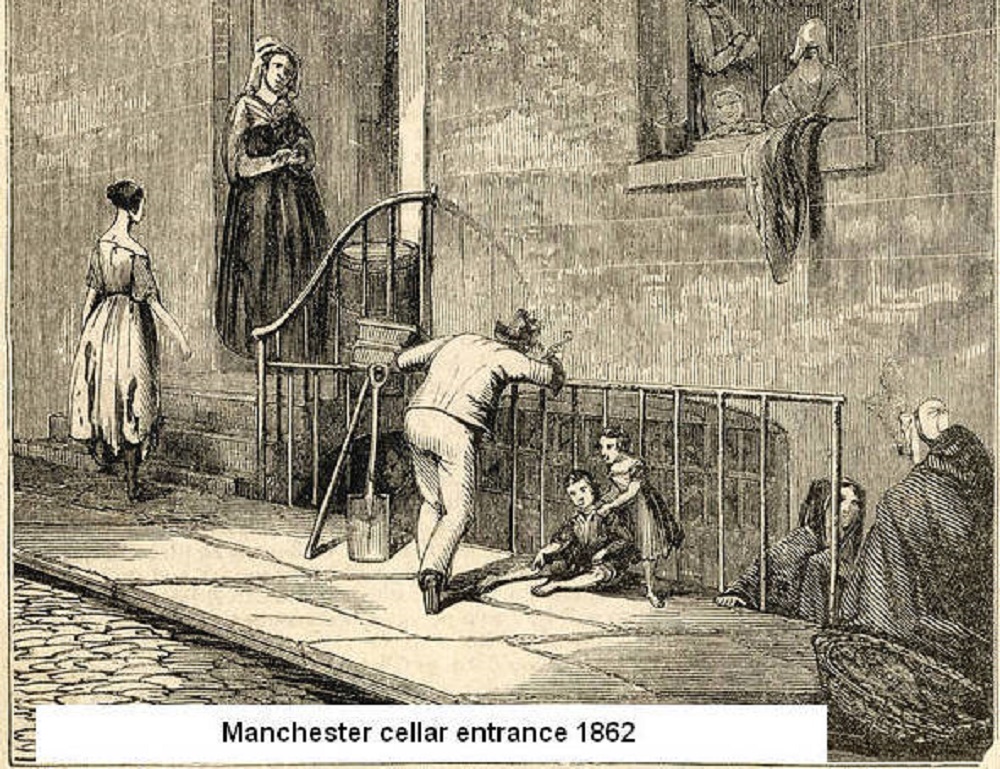

A plot of land with a footprint of 24ft by 10 ft (approx 7.3m x 3m) would normally house 2 or more families, plus lodgers, whose total rent was 6 or 7 shillings (30 or 35p) per week. Properties with cellar dwellings below could yield an additional 2 to 4 shillings. Housing density was unprecedented, yet speculators were convinced still more profit could be squeezed from their investments. The solution they came up with was ‘closed courts’.

Housing density was unprecedented, yet speculators were convinced still more profit could be squeezed from their investments. The solution they came up with was ‘closed courts’.

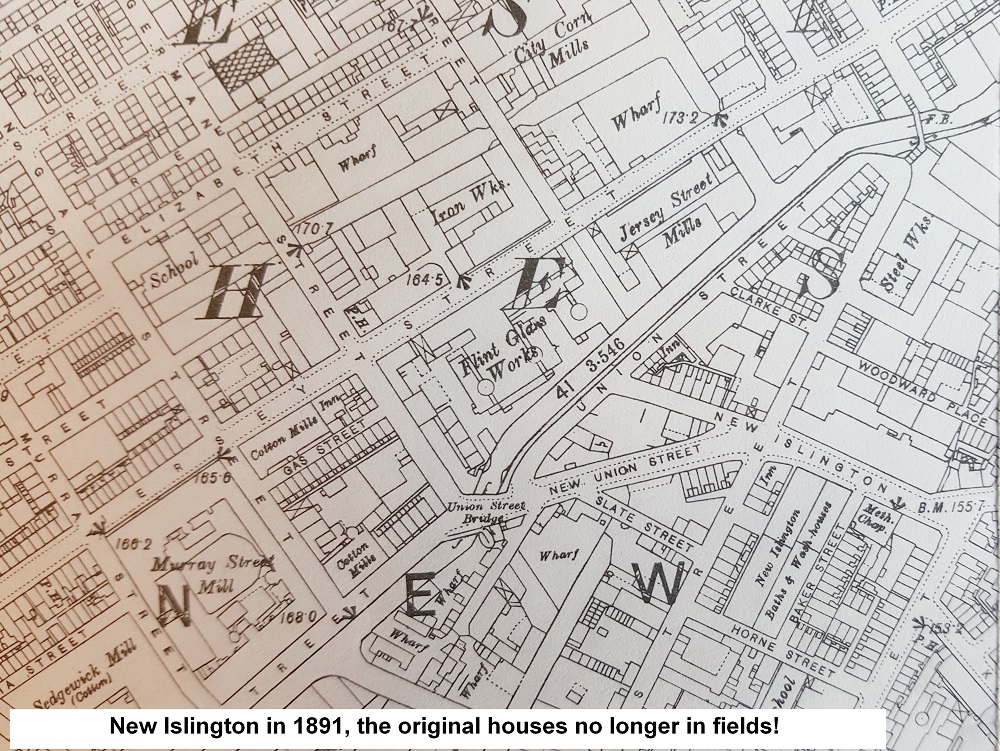

As his home in New Islington became surrounded by these new dwellings, great grandfather William would have observed humans packed into them like battery hens.

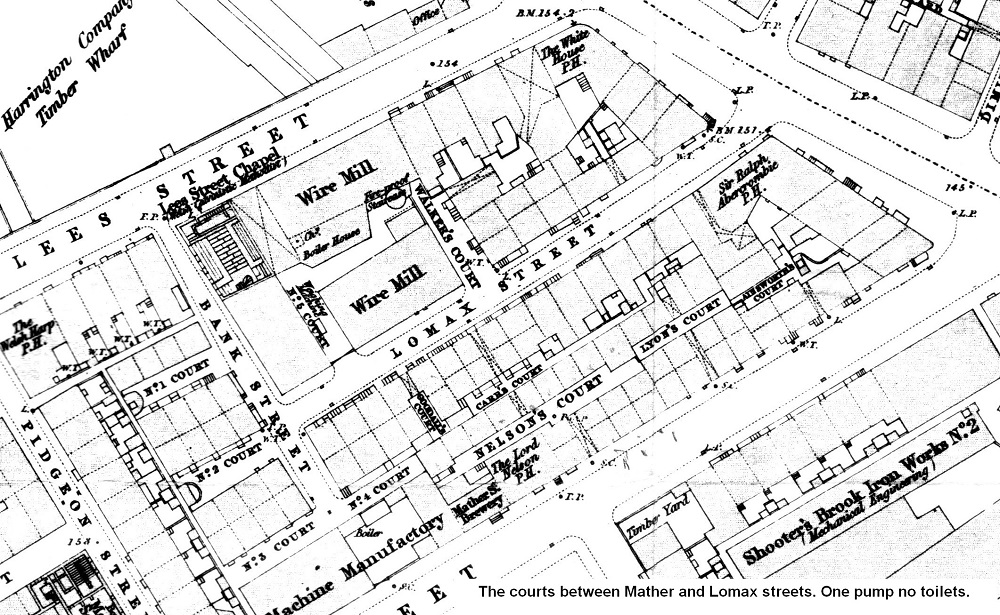

A prime example of uncontrolled speculation was hidden away behind two parallel thoroughfares, then called Lomax and Mather Streets (off Great Ancoats Street). Access to the seven inter-connecting ‘closed courts’ was by covered ginnels, 3 to 4 foot wide. Hundreds of people in the seven courts were served by a single pump. It was situated in the 4 foot wide Kerr’s Court which had 5 one up/one down houses with cellars. Until the corporation’s bye laws were implemented in the last quarter of the century, no sanitary provision whatsoever existed in some of the courts.

Access to the seven inter-connecting ‘closed courts’ was by covered ginnels, 3 to 4 foot wide. Hundreds of people in the seven courts were served by a single pump. It was situated in the 4 foot wide Kerr’s Court which had 5 one up/one down houses with cellars. Until the corporation’s bye laws were implemented in the last quarter of the century, no sanitary provision whatsoever existed in some of the courts.

William Sutcliffe’s great grandson Thomas was born at number 1 New Islington in 1872. By that time, a programme of ‘knocking through’ had been introduced. The dividing walls between each of the one up/one down dwellings was breached to turn them into four roomed houses. Closed courts were opened up by demolishing half the properties to make space for the back entries and individual yards we know today. According to corporation bye-laws, each house should have its own cold tap, and outside lavatory.

My grandmother Rachel (daughter of Thomas Sutcliffe) was married in 1918, and by that time the family had moved to Collyhurst. Once my grandparents could scrape together ‘key money’ (deposit), they moved into a rented house in Culvert Street.

I still have the front door key to that typical two up/two down (cold tap and outside lav.) where my mother and her siblings grew up.

In 1936, Culvert Street was about to be demolished to make way for ‘Collyhurst flats’. My grandparents were offered the 3 bedroomed house in Moston where I was born. It had gardens back and front, a bathroom, hot water and indoor toilet.

In the 160 years between William Sutcliffe’s birth and my own, an amazing transformation had taken place in working class life. By the 1950s, an ordinary working man could aspire to a solidly built house at a rent the family could afford – how different from today’s New Islington.