The footpath between New Moston and Failsworth nowadays passes beneath the Oldham Metrolink line by a fairly insignificant subway, notable only for constant flooding in heavy rain. In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten…

In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten…

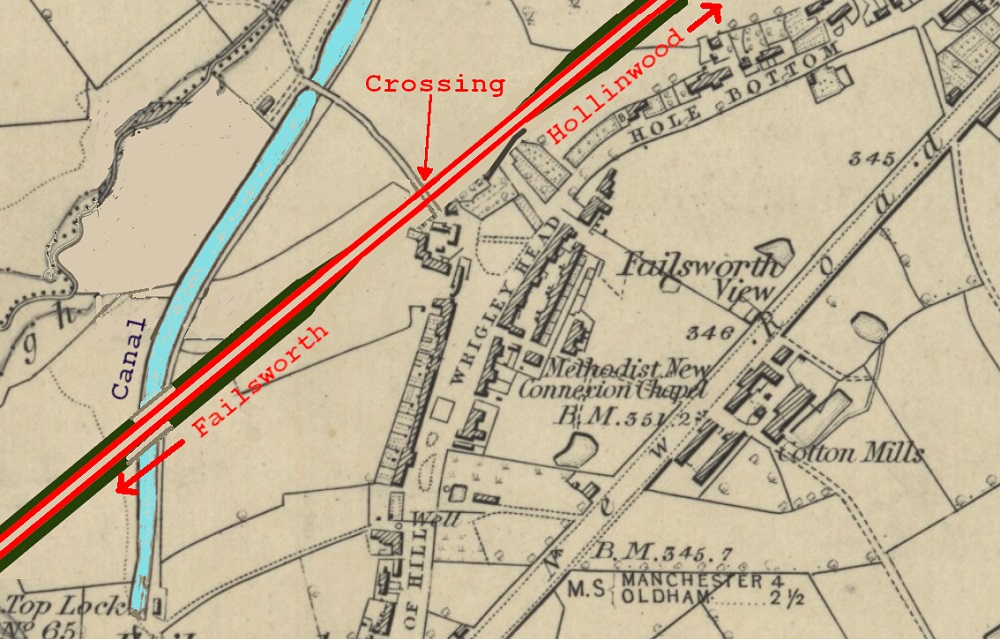

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway had proposed a branch from Newton Heath to the rapidly-expanding coal and cotton district of Hollinwood in 1872. Powers to build it, with an extension to Oldham, were granted in 1875, construction beginning the following year. Although it provided an easier route than by the fearsome incline from Middleton Junction to Werneth, the Hollinwood Branch nevertheless involved some stiff gradients and major earthworks, with many cuttings and embankments.

The section near Wrigley Head, Failsworth, was the only stretch level with the surrounding land and coincidentally met the existing footpath here, so a gated level crossing was provided. The line was opened in May 1880, two years behind schedule, but a major flaw was soon exposed. The crossing, past which trains were travelling at their fastest, had no signal box or lights, only ‘Whistle’ warning signs for engine drivers, about 70 yards either side. The railway company had evidently assumed there would not be many people using the crossing, and that anyone wishing to cross could easily summon a gate attendant: they were wrong on both counts. At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system.

At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system.

At around 11am on Friday, 10 September 1880, Elizabeth Salt, a fish-seller from Elias St, Miles Platting, had been showing her wares to the crossing keeper and set off towards New Moston, despite seeing a train approaching from the Dean Lane direction (Failsworth did not yet have a station). She was repeatedly warned to wait until the train had passed, but decided to chance it – she was struck by the engine, travelling at about 25 mph, and killed instantly. An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later.

An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later.

Failsworth station opened in April 1881 and later that year the railway company applied for powers to build a footbridge to replace the crossing. At some stage the company decided instead on a subway, which could be made wider and accommodate carts. By February 1882 work had still not begun, and the Failsworth and Moston local Boards were pressing the company for feedback.

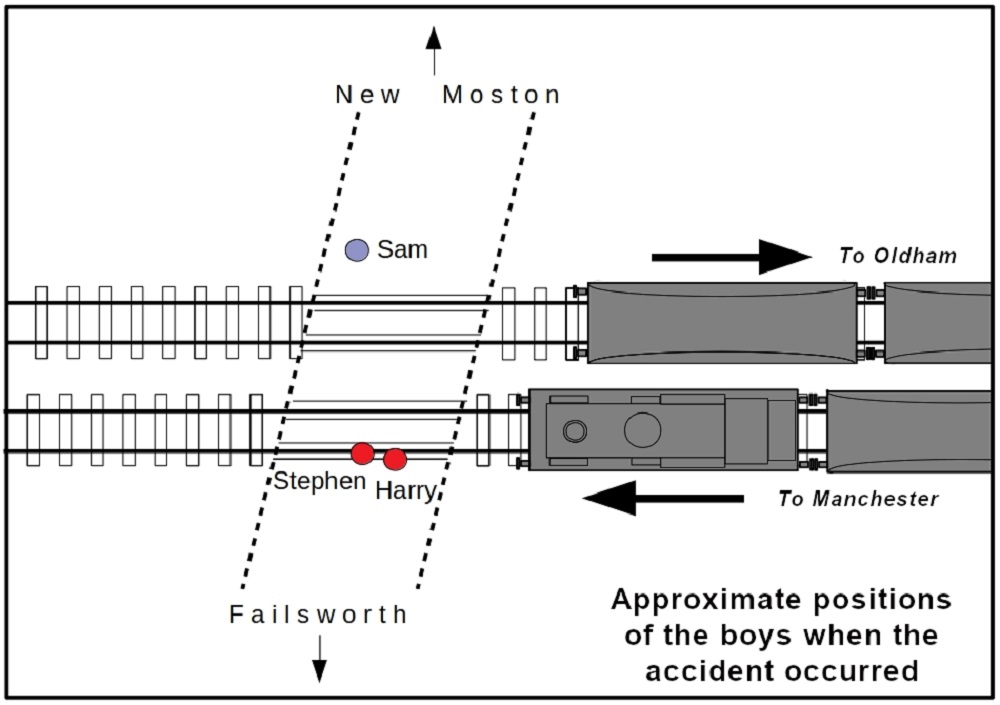

So, to the night of Thursday, 30 August 1883. Two boys aged nine and eight, Stephen and Henry (Harry) Bullows of Ricketts Street, New Moston, were sent on an errand by their father to buy bread in Failsworth. They were joined near the crossing by a friend, Samuel Stringfellow from Jones Street. When the boys returned, about 8:20pm, it was getting dark and, seeing no-one at the gates, Sam crossed first but heard an Oldham-bound train approaching and called to the others to wait, which they did. What they did not see, or hear, was that another train was bearing down on them from the Oldham direction. Perhaps its sound was masked by that of the receding train. Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed.

Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed.

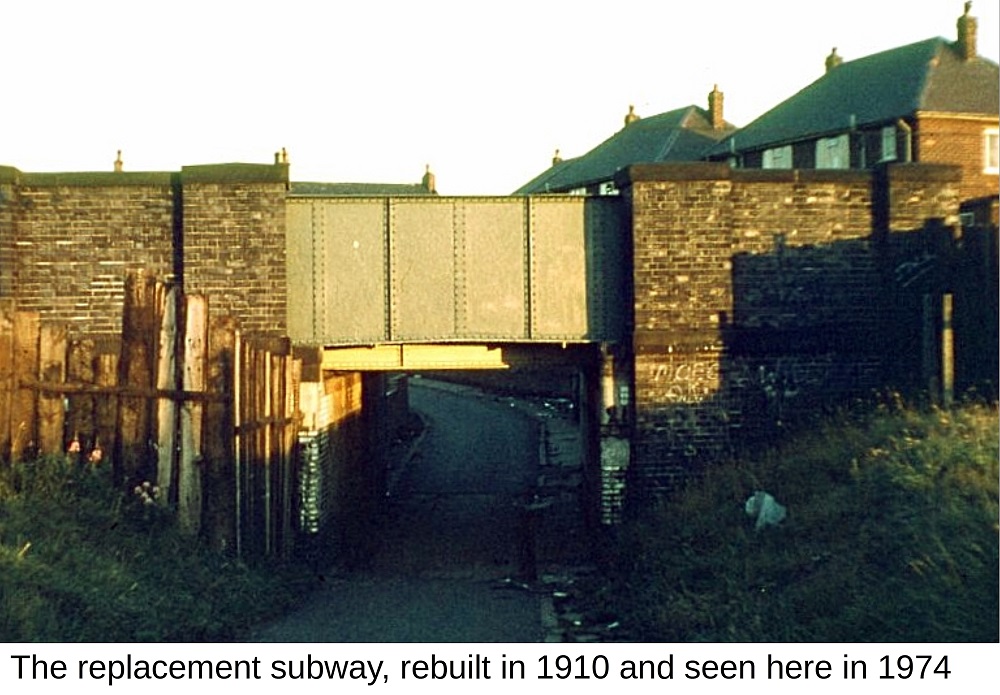

Another Sun Inn inquest followed, conducted by the same coroner as in 1880 – this time, although no individuals were blamed, the failure to replace the crossing after the first fatality caused the company to come in for severe criticism. They were ordered to put the subway work in hand as soon as possible, in consultation with the Failsworth Board, and to install lights and permanent watchmen at the crossing in the meantime. The brothers were laid to rest at St. Mary’s churchyard, Moston. After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history.

After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history.

With the industrial revolution came a massive increase in demand for leather, not only for shoes and clothing for the growing population, but for the accoutrements of the steam age: belts to drive machinery, protective aprons, masks and gloves, piston glands and all manner of other bits and bobs. Thomas Kershaw was named as the tanner in Failsworth, when he married in October 1769, and took on an apprentice in 1771.

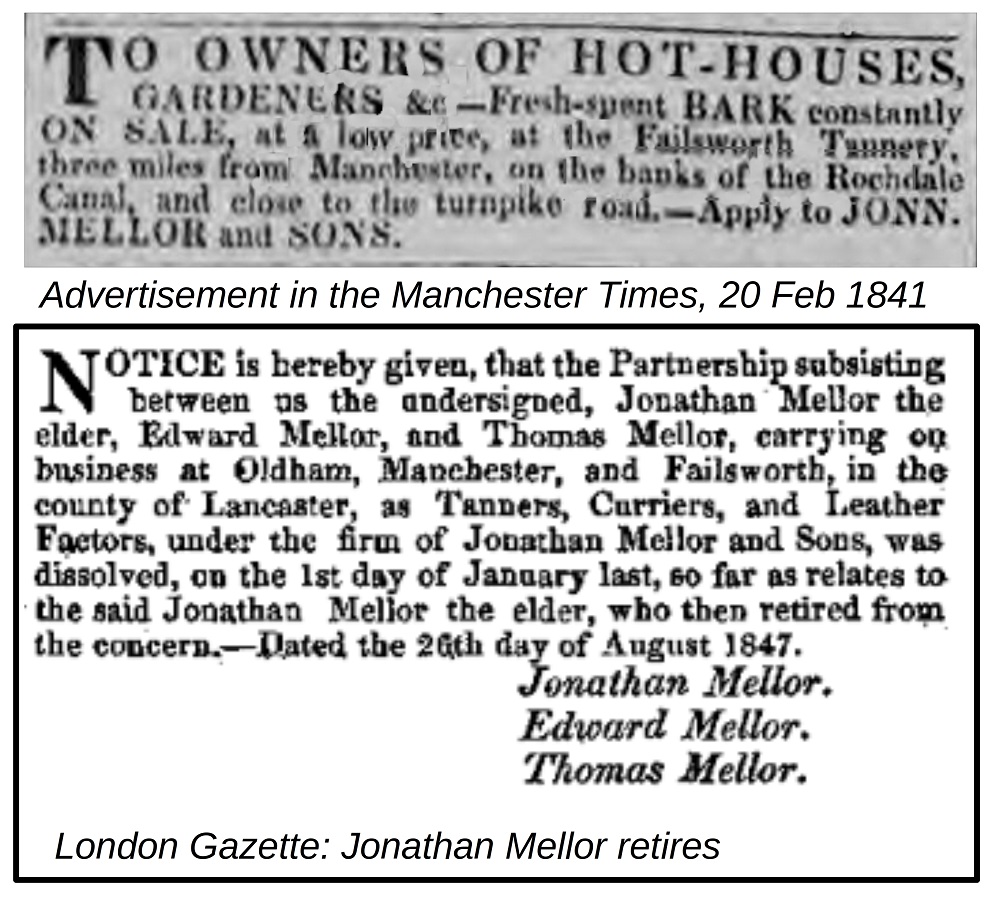

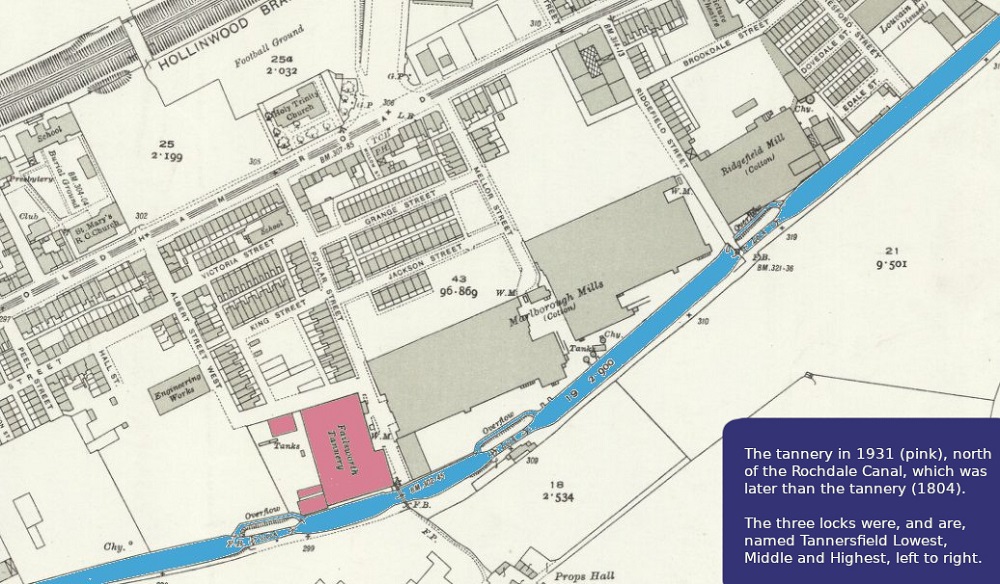

With the industrial revolution came a massive increase in demand for leather, not only for shoes and clothing for the growing population, but for the accoutrements of the steam age: belts to drive machinery, protective aprons, masks and gloves, piston glands and all manner of other bits and bobs. Thomas Kershaw was named as the tanner in Failsworth, when he married in October 1769, and took on an apprentice in 1771. Jonathan retired in 1847, leaving the tannery in the capable hands of his sons; he died two years later and was buried at Oldham parish church, where he had held a pew since 1842. Edward decided to concentrate on the mill interests in Rochdale, leaving Thomas in sole charge of the tannery from 1854. Unlike his father, who had resided on King St, Oldham up to his death, Thomas moved to Failsworth, living at Rich Field House, Dob Lane, and later becoming a J.P. and Poor Law Guardian.

Jonathan retired in 1847, leaving the tannery in the capable hands of his sons; he died two years later and was buried at Oldham parish church, where he had held a pew since 1842. Edward decided to concentrate on the mill interests in Rochdale, leaving Thomas in sole charge of the tannery from 1854. Unlike his father, who had resided on King St, Oldham up to his death, Thomas moved to Failsworth, living at Rich Field House, Dob Lane, and later becoming a J.P. and Poor Law Guardian. Around 1880, Thomas moved to Firs Hall, Failsworth, where he died in 1889, aged 81. Sir Edward Watkin (knighted in 1868) attended his funeral at Failsworth cemetery. His son, Robert, who had been born in Failsworth around 1853, took charge of the tannery, which then became “Robert Mellor Ltd”. In 1890, Robert married Eliza Melland of Bowdon, Cheshire, and moved to Disley.

Around 1880, Thomas moved to Firs Hall, Failsworth, where he died in 1889, aged 81. Sir Edward Watkin (knighted in 1868) attended his funeral at Failsworth cemetery. His son, Robert, who had been born in Failsworth around 1853, took charge of the tannery, which then became “Robert Mellor Ltd”. In 1890, Robert married Eliza Melland of Bowdon, Cheshire, and moved to Disley. The firm continued as Robert Mellor Ltd after his death and was listed as ‘sole-leather tanners’ in international directories, evidence of export as well as home markets. Another misfortune befell the firm when a fire broke out in the early hours of Saturday, 4 July 1914. The exact cause was never established, but it was reported that fifty firemen attended the blaze, which nevertheless destroyed most of the warehouse and around £12,000 worth of finished leather. Bystanders also said a large number of rats were seen dashing out and jumping into the canal!

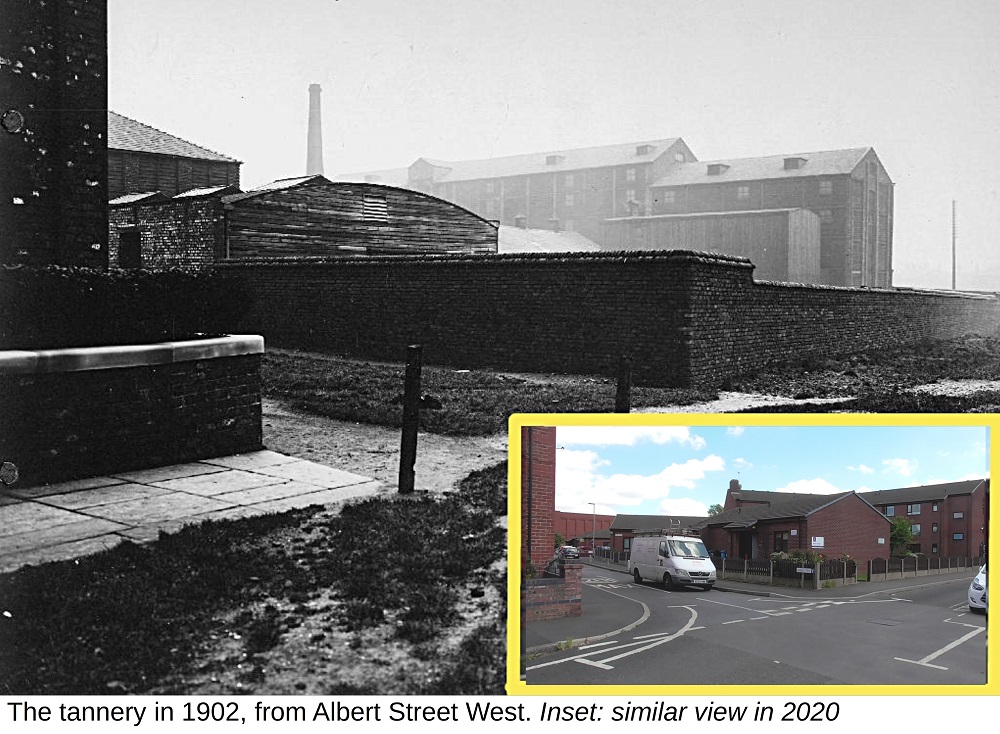

The firm continued as Robert Mellor Ltd after his death and was listed as ‘sole-leather tanners’ in international directories, evidence of export as well as home markets. Another misfortune befell the firm when a fire broke out in the early hours of Saturday, 4 July 1914. The exact cause was never established, but it was reported that fifty firemen attended the blaze, which nevertheless destroyed most of the warehouse and around £12,000 worth of finished leather. Bystanders also said a large number of rats were seen dashing out and jumping into the canal! The tannery continued to be listed in telephone books up to 1930, but appears to have closed by 1935. Nothing now remains: the Home Guard Club and wooden garages were built on the site in the 1960s, with bungalows and flats added later. The leather trade is still with us, of course, now utilising different, largely mechanised, processes, but there is still one traditional oak bark tannery at Colyton in Devon.

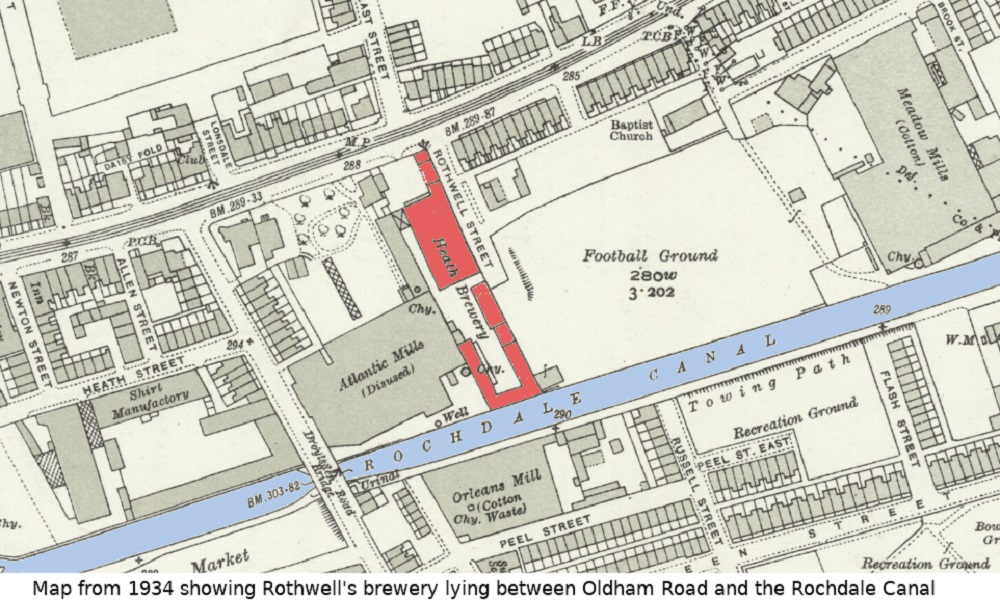

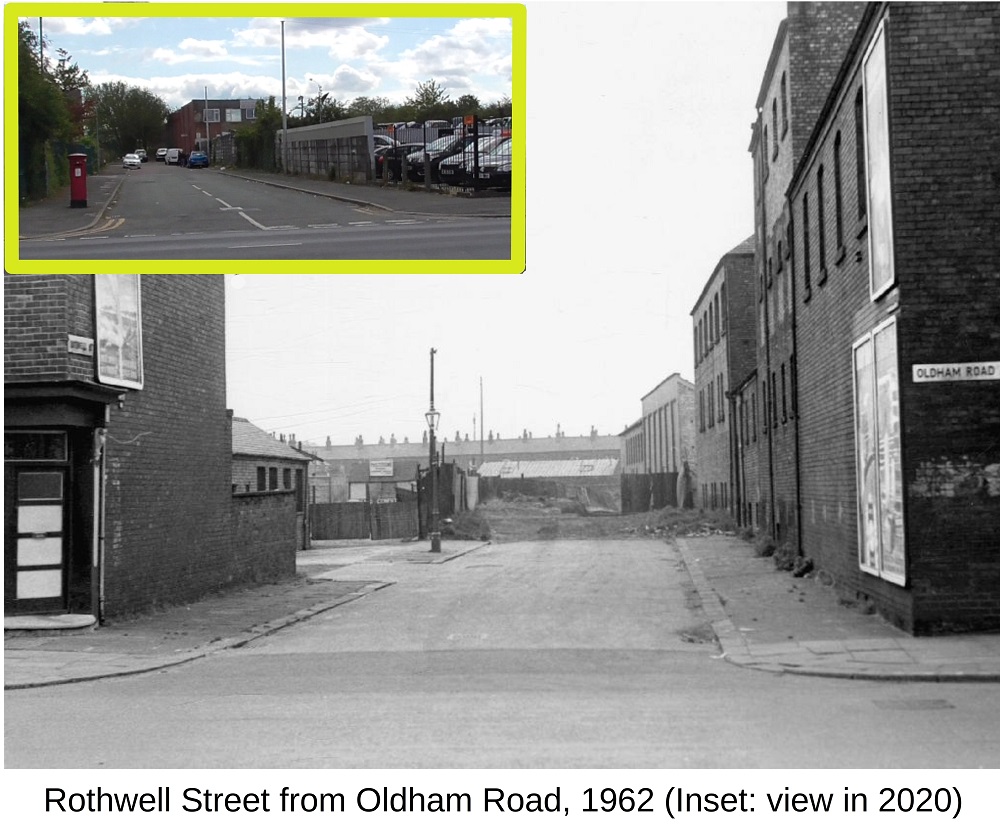

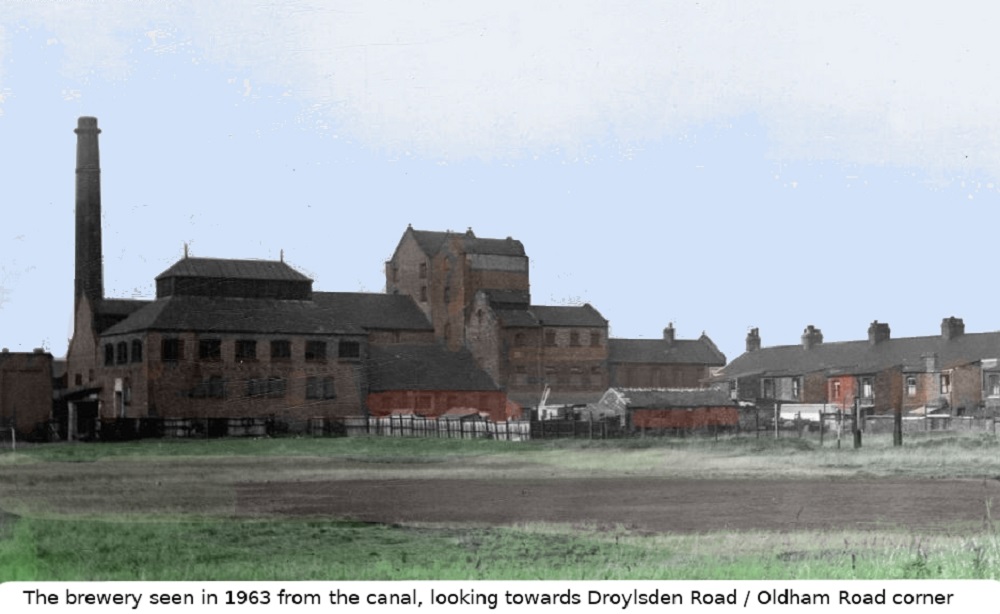

The tannery continued to be listed in telephone books up to 1930, but appears to have closed by 1935. Nothing now remains: the Home Guard Club and wooden garages were built on the site in the 1960s, with bungalows and flats added later. The leather trade is still with us, of course, now utilising different, largely mechanised, processes, but there is still one traditional oak bark tannery at Colyton in Devon. William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery.

William Thomas Rothwell was born at the curiously named Spout Bank in Heap, near Bury, in 1844, the son of farmer John and his wife Martha. It seems William did not wish to follow his father into farming, because by 1870 he is listed as secretary of the Bury Brewery Company, founded in 1861 on George Street. The 1871 Census gives his occupation as ‘innkeeper and brewer’ living at 96 Georgiana Street, round the corner from the brewery. William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33.

William’s brother Frederick joined him in the business, living across the road on Dob Lane, Failsworth, but suffered a fatal accident on 10 July 1886, when a wort pan boiled over, badly scalding him from the neck down. He was taken to William’s house but despite being attended by doctors, died 3 days later; he was only 33. Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such.

Rival brewers Wilson’s had far more tied houses than Rothwells, who had only 40 or 50; mostly around Newton Heath and Failsworth with a handful in places such as Ashton, Oldham or Stalybridge. A few of these disappeared early in the 20th century, such as the Farmyard Tavern (which it was, literally) on Ten Acres Lane, which closed in 1917. However, quite a few former Rothwells pubs have survived, although you would be forgiven for not recognising them as such. Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth).

Despite the takeover, many of the pubs still sported Rothwell signage, in tilework, over doorways, or in etched glass windows, for many years. Although refurbishment has removed all traces of their previous ownership nowadays, surviving pubs include the New Crown (Newton Heath), Fox Inn (Stalybridge) and the Wheatsheaf, Pack Horse, Bay Horse, Mare & Foal, Cotton Tree and Dutch Birds (all in Failsworth). The Black Horse in 2009

The Black Horse in 2009