The footpath between New Moston and Failsworth nowadays passes beneath the Oldham Metrolink line by a fairly insignificant subway, notable only for constant flooding in heavy rain. In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten…

In the 1880s, this spot had a notoriety now long forgotten…

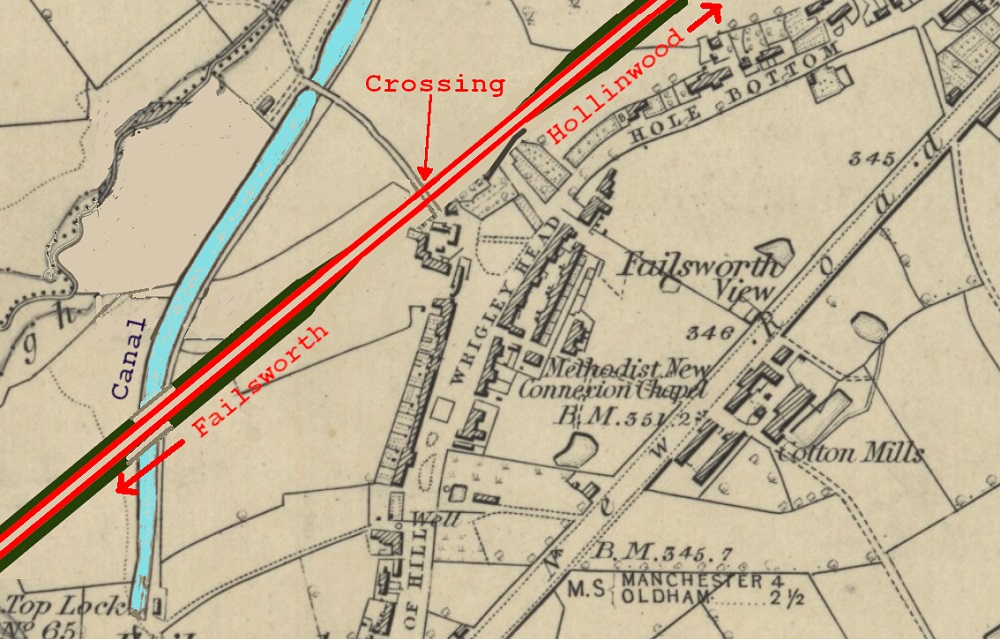

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway had proposed a branch from Newton Heath to the rapidly-expanding coal and cotton district of Hollinwood in 1872. Powers to build it, with an extension to Oldham, were granted in 1875, construction beginning the following year. Although it provided an easier route than by the fearsome incline from Middleton Junction to Werneth, the Hollinwood Branch nevertheless involved some stiff gradients and major earthworks, with many cuttings and embankments.

The section near Wrigley Head, Failsworth, was the only stretch level with the surrounding land and coincidentally met the existing footpath here, so a gated level crossing was provided. The line was opened in May 1880, two years behind schedule, but a major flaw was soon exposed. The crossing, past which trains were travelling at their fastest, had no signal box or lights, only ‘Whistle’ warning signs for engine drivers, about 70 yards either side. The railway company had evidently assumed there would not be many people using the crossing, and that anyone wishing to cross could easily summon a gate attendant: they were wrong on both counts. At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system.

At that time, just off Wrigley Head, there was a small group of dwellings, known for a time as Bridge Street, and at one of these lived coal miner John Cooper, his wife Elizabeth and four children. Elizabeth was given responsibility for attending to the gates, evenings only, but all day on alternate Sundays. For this, the L&YR paid an allowance of 2s 6d per week. A full-time attendant was provided, but only during the day. It should perhaps have been obvious that, even part-time, entrusting the crossing to an ordinary citizen, no doubt with distractions of her own, was hardly a reliable system.

At around 11am on Friday, 10 September 1880, Elizabeth Salt, a fish-seller from Elias St, Miles Platting, had been showing her wares to the crossing keeper and set off towards New Moston, despite seeing a train approaching from the Dean Lane direction (Failsworth did not yet have a station). She was repeatedly warned to wait until the train had passed, but decided to chance it – she was struck by the engine, travelling at about 25 mph, and killed instantly. An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later.

An inquest was held on Monday, 13 September at the Sun Inn in Failsworth, at which the coroner (Frederick Price) returned a verdict of accidental death, but criticised the L&YR Company for having wholly inadequate safeguards at what was already proving to be a very busy – and dangerous – crossing. It was stated that several hundred people crossed the line every day, for work, shopping or to attend schools. Elizabeth, 38, was buried at St. John, Failsworth, two days later.

Failsworth station opened in April 1881 and later that year the railway company applied for powers to build a footbridge to replace the crossing. At some stage the company decided instead on a subway, which could be made wider and accommodate carts. By February 1882 work had still not begun, and the Failsworth and Moston local Boards were pressing the company for feedback.

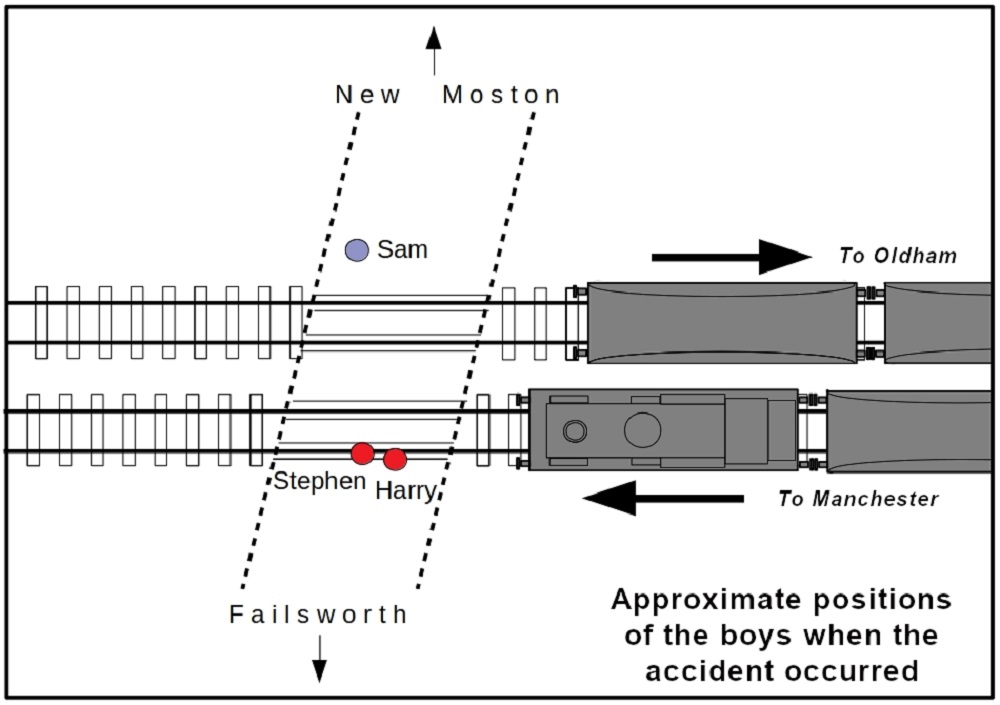

So, to the night of Thursday, 30 August 1883. Two boys aged nine and eight, Stephen and Henry (Harry) Bullows of Ricketts Street, New Moston, were sent on an errand by their father to buy bread in Failsworth. They were joined near the crossing by a friend, Samuel Stringfellow from Jones Street. When the boys returned, about 8:20pm, it was getting dark and, seeing no-one at the gates, Sam crossed first but heard an Oldham-bound train approaching and called to the others to wait, which they did. What they did not see, or hear, was that another train was bearing down on them from the Oldham direction. Perhaps its sound was masked by that of the receding train. Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed.

Sam’s last view of them was of Stephen attempting to hold Harry back. As the trains disappeared into the gloom, Sam could not at first see his friends, but then noticed a shredded handkerchief lying on the track. He raised the alarm and John Cooper, coming out to see what the commotion was, discovered one of the boys, decapitated, beside the line; the other lay badly mutilated nearby, and died shortly afterwards. Sam ran to Ricketts Street, met on the way by a couple of other friends, to give John Bullows the terrible news that his lads had been killed.

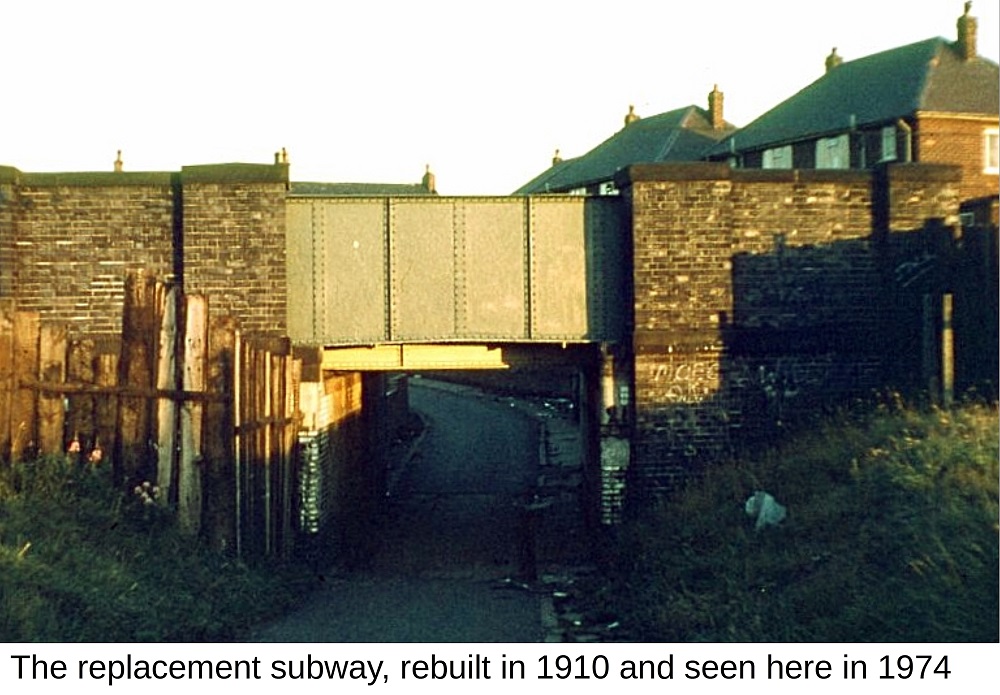

Another Sun Inn inquest followed, conducted by the same coroner as in 1880 – this time, although no individuals were blamed, the failure to replace the crossing after the first fatality caused the company to come in for severe criticism. They were ordered to put the subway work in hand as soon as possible, in consultation with the Failsworth Board, and to install lights and permanent watchmen at the crossing in the meantime. The brothers were laid to rest at St. Mary’s churchyard, Moston. After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history.

After a couple more false starts, the subway was eventually built (1884-5), the Bridge Street properties being demolished to make room for it. It was renewed around 1910 and lasted in this form until 2010, when the side walls and decking were replaced during Metrolink conversion, giving its present appearance. The path remains as busy as ever, but few people now give the subway a second glance, or have any inkling of its dark history.

It seems an age ago but, on Thursday 12th March this year, I went to see Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ at NWTAC’s theatre on Lightbowne Road. Not for the first time, they took me by surprise.

It seems an age ago but, on Thursday 12th March this year, I went to see Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ at NWTAC’s theatre on Lightbowne Road. Not for the first time, they took me by surprise. Rehearsals continued remotely for the theatre’s students using the on-line meeting platform, Zoom. The empty theatre was re-painted and steam cleaned in readiness.

Rehearsals continued remotely for the theatre’s students using the on-line meeting platform, Zoom. The empty theatre was re-painted and steam cleaned in readiness. NWTAC are continuing to work on projects including ‘The Sound and Soul of Hitsville Mowtown’ to be staged in November and the pantomime ‘Puss in Boots’ throughout December. This weekend, for two nights only on 16th and 17th October, Beth Singh will perform live at the theatre.

NWTAC are continuing to work on projects including ‘The Sound and Soul of Hitsville Mowtown’ to be staged in November and the pantomime ‘Puss in Boots’ throughout December. This weekend, for two nights only on 16th and 17th October, Beth Singh will perform live at the theatre. Until mass vaccination all but eradicated whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever, their spectres remained ever present, especially in poorer areas.

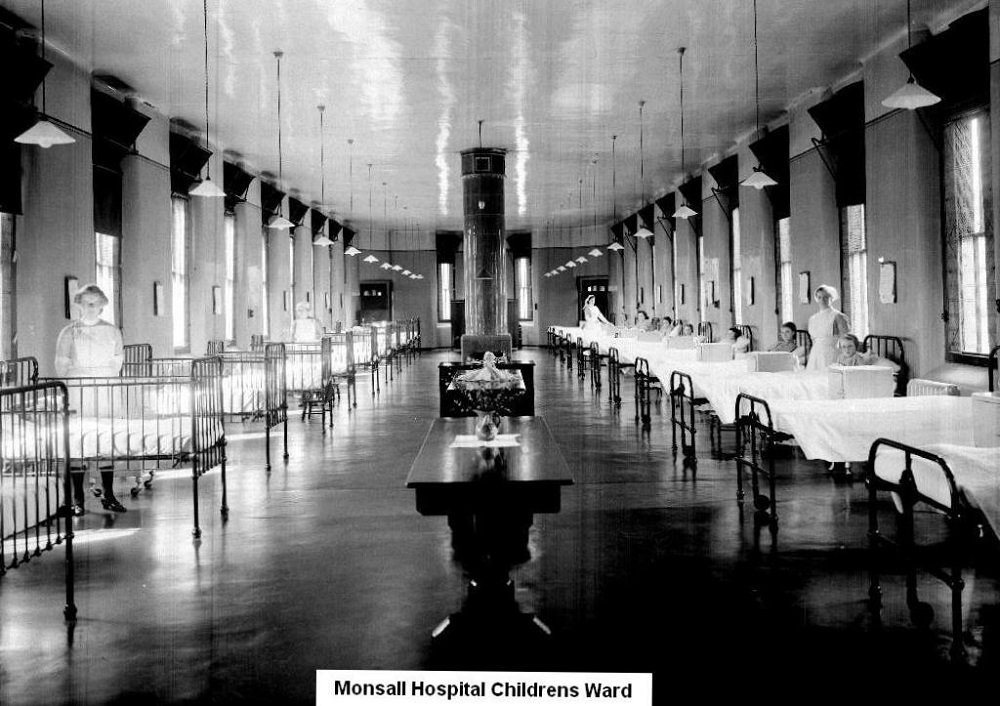

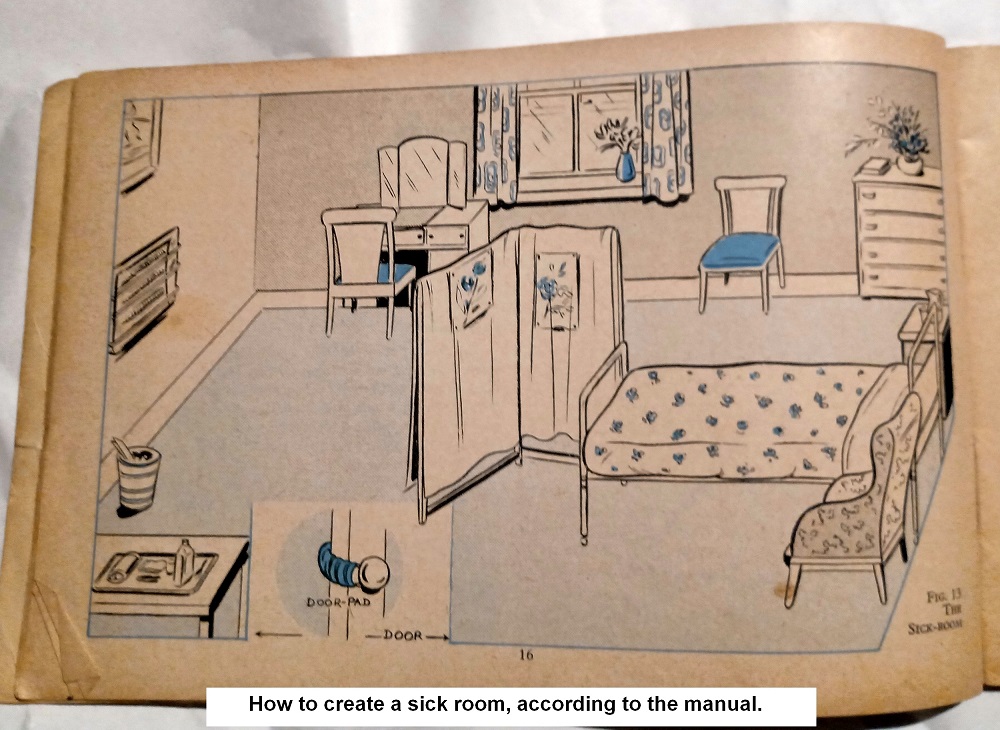

Until mass vaccination all but eradicated whooping cough, diphtheria and scarlet fever, their spectres remained ever present, especially in poorer areas. In the fifties, the belief was that, sooner or later, every child would contract mumps, chicken pox and measles. To get it over with quickly, we were sent to play at the homes of contagious friends.

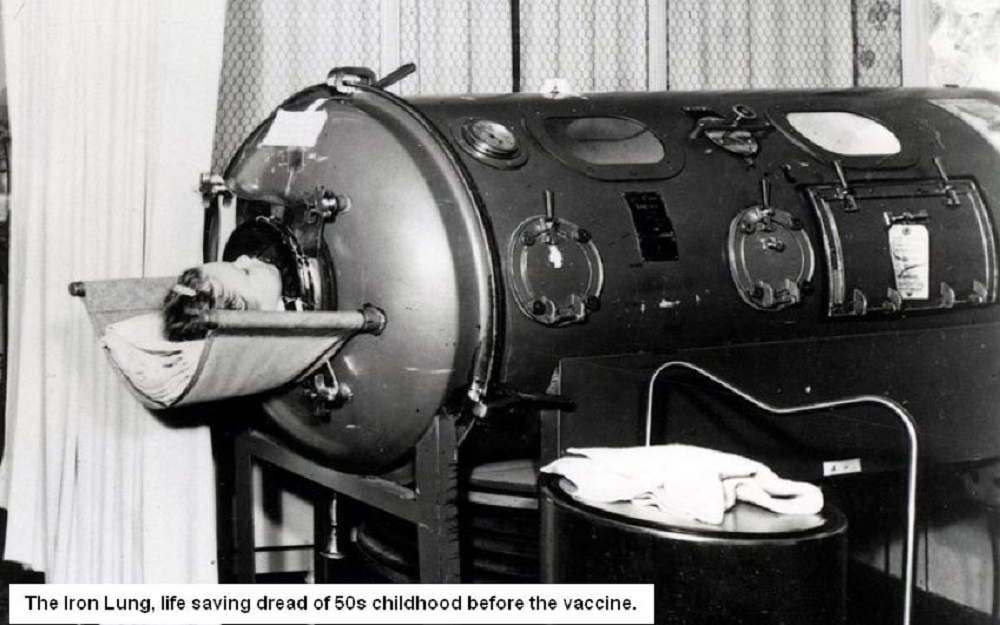

In the fifties, the belief was that, sooner or later, every child would contract mumps, chicken pox and measles. To get it over with quickly, we were sent to play at the homes of contagious friends. Throughout my childhood, TB and polio were the demon diseases. When I was about 9, there was a polio scare. Banner headlines exhorted parents not to allow children near open water. The previous afternoon, my friend Anne and I had been up to our welly tops in the Moston Brook, trying to build a dam. We kept the escapade from our parents, but visions of ‘iron lungs’ and metal leg callipers haunted our thoughts.

Throughout my childhood, TB and polio were the demon diseases. When I was about 9, there was a polio scare. Banner headlines exhorted parents not to allow children near open water. The previous afternoon, my friend Anne and I had been up to our welly tops in the Moston Brook, trying to build a dam. We kept the escapade from our parents, but visions of ‘iron lungs’ and metal leg callipers haunted our thoughts. Later, a polio vaccine became available. Subsequently it would be administered as syrup or on a sugar lump, but for us it was the dreaded ‘prick’, as injections were then commonly known.

Later, a polio vaccine became available. Subsequently it would be administered as syrup or on a sugar lump, but for us it was the dreaded ‘prick’, as injections were then commonly known. Eventually my tonsils burst, and had to be removed at Booth Hall. Two days in hospital was followed by a fortnight off school to convalesce.

Eventually my tonsils burst, and had to be removed at Booth Hall. Two days in hospital was followed by a fortnight off school to convalesce. Although complaints from the past seem to be re-surfacing, I don’t hear anyone mentioning chilblains these days. Girls at my school were repeatedly warned not to stand against the cloakroom radiators as it would only increase the agony. And as yet, I haven’t spotted a ring worm sufferer with a shaven head adorned with Gentian Violet. And when did they stop painting it on throats?

Although complaints from the past seem to be re-surfacing, I don’t hear anyone mentioning chilblains these days. Girls at my school were repeatedly warned not to stand against the cloakroom radiators as it would only increase the agony. And as yet, I haven’t spotted a ring worm sufferer with a shaven head adorned with Gentian Violet. And when did they stop painting it on throats?