The celebrated folklorists Peter and Iona Opie, authors of ‘The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren’, describe crossing Manchester on a May Day in the 1950s and seeing children across the city taking part in May Day customs.

Until the mid-1960’s May Day customs were widespread in Manchester and Salford. They were of two kinds. One was Molly Dancing. The other was where young girls of a street, with assistance from mothers, would choose and dress a May Queen.

In 1983 an appeal for May Day memories appeared in the Manchester Evening News, what follows is based on the replies.

Mrs D. Thompson writing of her childhood in Longsight:

“We has a wonderful day on May Day. We would be getting things ready for weeks before, having rehearsals and trying on different clothes – out mother’s and fathers.

Girls that could get a white dress (few could afford one), would be the ones who would dance around the maypole.

We would put our names in a hat, and whoever was chosen would be May Queen, and we would dress her up on May Day. An old chair dressed in coloured paper would be her throne. The maypole, an old washing prop, also covered in paper and ribbons.

We has eight long ribbons coming from the top, and as the girls wound in and out round the pole, it would plat itself all down the pole.”

Helen Fedosijewski, born 1909 in Harpurhey recalled ‘The Maypole song’:

- Around this Merry Maypole

- And through the live long day

- For gentle (girl’s name) is crowned the queen of May

- Joy, Joy, Joy, dance and sing, sing and dance

- We shall all have hearts so gay

- Sing and dance, dance and sing, to make the woodlands ring

- All around the maypole, we shall trot,

- See what a maypole, we shall trot,

- See what a maypole, we have got,

- All our ribbons tied in a bow

- All around the merry maypole

- God save our gracious Queen (meaning our May queen, who was sat on a chair)

She continued “We also had a boy, a page, who carried the pole. We knocked on doors, and if we didn’t get any coppers, we didn’t finish the song, and went to the next house. We averaged about 11 pence each. The queen got a penny more, being dressed up in a lace curtain and white dress. All the mothers made paper flowers. It was WONDERFUL !”

Mrs B. Hodges wrote:

“Everything and everybody had to be in order. As the procession commenced, the whole retinue would knock at house doors.

The Queen stood between her two maids, framed in a ‘garf’, a wooden half-hoop, dressed for the occasion. When the householder opened their door, the May dancers would dance around the pole singing:

Cheese and bread, the whole cow’s head, roasting in a lantern. A bit for you, a bit for me, and a bit for the molly dancers.

The queen would be praised, a few coppers put in the box. We would say thank you, and move to the next house. The children enjoyed the planning and plotting. It was a happy time.

Each street had their May Queen, and there was rivalry to be the best. There would be three or four maypoles, from other streets, who would come round and knock on doors in our street – each one with their own Queen and dancers, But, ‘it was considered bad luck, to sing in a street where another May Queen was singing.”

This is an account describing Lowcock Street, Lower Broughton in the 1940’s:

“Great care was taken to get everything just so. It took many nights after school practicing in somebody’s back yard, so nobody from other streets could see. On May Day we would hurry from school, have our tea, then the great time would begin. One child carried a box for the money.

After we had collected our pennies, we would go to a back yard, and have a count up. Then there would be a party, cake, pop, crisps, sweets, biscuits – it was really something, and then we would have a concert, each child either saying a poem, or singing a song.

The Queen’s train would be carefully folded, and returned along with the brush stale and mother’s dress. If there was any money left, it was always shared out.”

Mrs H Thompson wrote of her own childhood in Gorton (1921-26) and her daughter’s in Reddish (1945-51).

‘There were about ten of us and we had quite a feast. Afterwards we would have an impromptu concert, with much giggling; boys hanging around the back yard door.”

Miss E. Chamberlain of Hulme included the words to five different songs, the last of which was:

- “Last year we had a Maypole. It was a pretty sight.

- And all the children in it, were dressed in pink and white.

- With hearts and voices joining, Queen merrily reigns today.

- For gentle (girl’s name), is crowned the Queen of May.”

The May Day customs occurred in the inner suburbs of Manchester and Salford, encircling the City Centre. From Hulme in the west, through Salford and across to Cheetham Hill, Collyhurst, Harpurhey, Moston, Newton Heath, and Gorton, to Reddish in the east, then south through Longsight, Ardwick and Chorlton on Medlock.

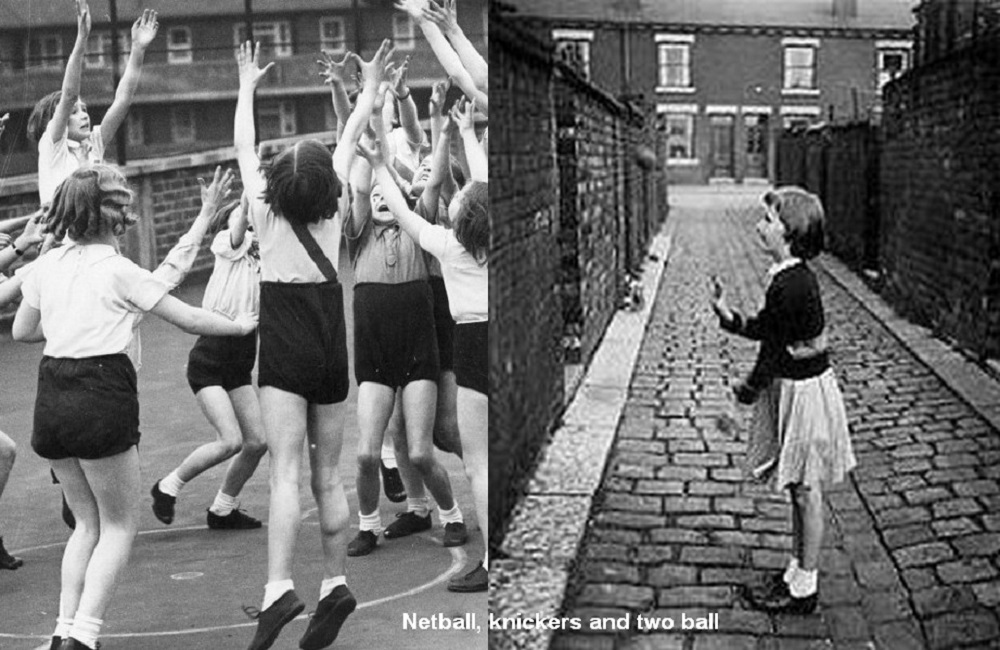

What strikes me is there was no involvement of schools or churches. The activities were street based, organized by the children themselves and passed from generation to generation.

When the Opies drove across Manchester on that May Day in the 1950s, they wouldn’t have been aware that the festivities they were witnessing, probably dating back to the Middle Ages, would have died out a decade later. The last account was from Rhodes Street, Miles Platting in 1966.