Is it me or are we heading for Christmas like a steam train? There’s so much going on. What a contrast compared to last year.

I’m a devoted Christmas ‘last minuter’ but got a ticket for NWTAC’s Winter Wonderland Concert back in November and, well, haven’t looked back. The curtains opened and the first line of the first song put a smile on our faces…”Sleigh bells, ring are you listening?”. We were treated then on to a fabulous mix of Christmas musical numbers and great dance routines: Let It Snow, Santa Claus is Coming to Town, White Christmas, Jingle Bell Rock, Sleigh Ride and Merry Christmas Everybody, This show had them all and comedy sketches too.

Brumbly the Elf, Inspector Brumbly that is, aka Anthony Horricks, went through some new ‘rules’ about Christmas and we had a peep inside the elves workshop.

‘The Nativity’ scene was just brilliant. A nativity in reverse, if that makes sense. The usual characters were played by grown-ups pretending to be children rather than the other way around and it had the audience in stitches.

The enthusiasm and love of performing shone through as it always does. The audience joined in with the cast to close the show with ‘I wish it could be Christmas Every Day’. Honestly, Brumbly the Elf wouldn’t have it any other way. It made me want to go home and put my Christmas tree up straight away. Me, with my ‘last minute’ reputation!

Next up for NWTAC is Aladdin. So, if you weren’t able to get to Winter Wonderland, get a shift on and book your tickets. Your kids will love it. YOU will love it.

Aladdin runs from 22 – 31 December 2021. Contact NWTAC for tickets or book through Groupon.

Here’s what’s in store…

A young dreamer, a beautiful princess, an evil magician, and a self-proclaimed beautiful Dame will keep you entertained in this spectacular Christmas show.

Next week the theatre is hosting The Black and White Mikado, a comic Gilbert and Sullivan opera performed by NMAODS (North Manchester Amateur Operatic & Dramatic Society). The costumes look AMAZING! It runs for 4 nights starting on Wednesday 8th so you’ll have to be quick.

There’s plenty more going on in and around Moston in the run up to Christmas and beyond into 2022. If you’re uneasy with indoor events then go outdoors… and that’s not a plug for an outdoor retailer, by the way.

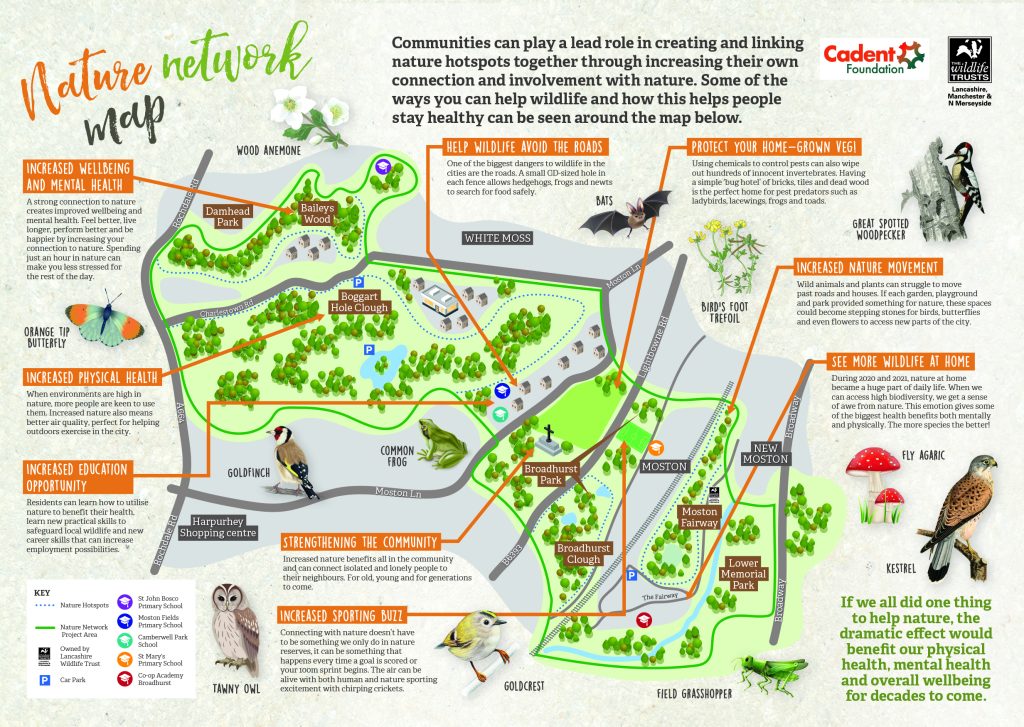

- North Manchester Fitness and Morisso Health recently led an Elf walk in Boggart Hole Clough. A great turn out. Keep an eye out as they both run regular outdoor activities and there’s something to suit everyone

- Simply Cycling are at Boggart Hole Clough Mondays and Saturdays

- Michael Green from Broadhurst Community Centre leads well-being walks throughout the week

- If you like gardening there are clubs at No 93 Church Lane, Moston as well as Failsworth Growing Hub next to Failsworth Library

- Join Russell Hedley from the Lancashire Wildlife Trust on Thursdays and give the local wildlife a hand by volunteering – it’s a great project to be part of

Finally, today Saturday 4th December, Moston switches its Christmas lights on at Moston Green festivities commence at 3pm and NWTAC will be there! Forget your tree for now, you can put it up tomorrow.

For information about NWTAC and this seasons shows, how to book tickets etc just click here or follow them on Facebook.

For NMAODS website, including booking tickets just click here or follow them on Facebook.